Let us envision: the year is 1823. The rugged Jurassic coastline of Dorset, England, whispers secrets of a long-vanished world. It was here, amidst the ancient rocks, that a groundbreaking discovery was about to rewrite our understanding of prehistoric marine life. For years, the imposing fossil remains of Plesiosaurus, a majestic marine reptile with a serpentine neck and paddle-like limbs, had captivated the scientific community. These giants, ruling the ancient seas for millions of years, were known only through their adult forms, leaving a gaping hole in our knowledge of their life cycle and development.

Then came the meticulous work of Mary Anning, a fossil collector and paleontologist whose keen eye and unwavering determination unearthed some of the most significant prehistoric finds of her era. Working in the challenging conditions of the Lyme Regis cliffs, Anning searched for the clues that nature had locked away in stone. The air often hung heavy with the salt spray of the English Channel and the damp earth of the eroding cliffs, but Anning pressed on, driven by an insatiable curiosity.

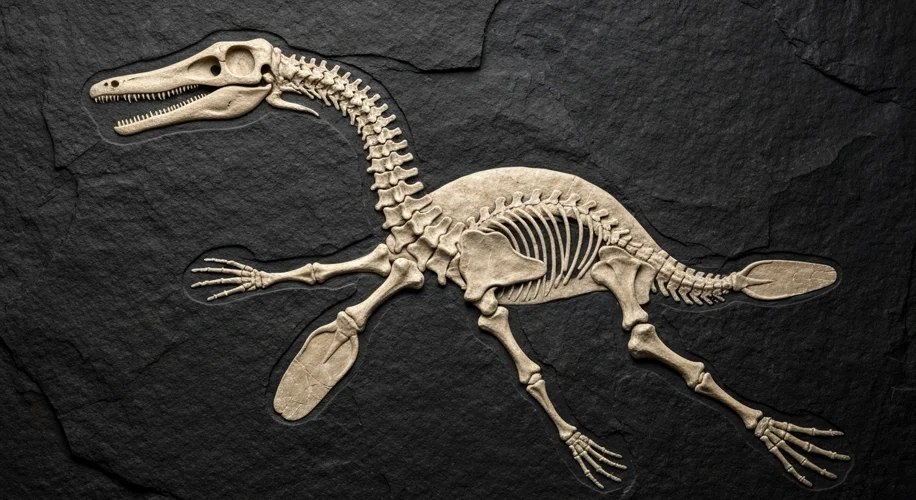

It was Anning who first recognized the significance of a particular fossil. Unlike the colossal skeletons of adult Plesiosaurus that had previously been found, this specimen was strikingly small. Its delicate bones, perfectly preserved, told a different story. It was the fossil of a juvenile Plesiosaurus, an individual that had not yet reached its full, formidable size. This was not just another fossil; it was a key, unlocking a 150-million-year-old mystery.

The discovery of this juvenile Plesiosaurus was a pivotal moment. Before this find, scientists could only speculate about how these marine predators grew. Did they hatch from eggs? How did their bodies develop from hatchlings to the immense creatures of legend? The juvenile fossil provided the first concrete evidence, offering a glimpse into the very beginnings of a Plesiosaurus‘s life. It suggested that, like many modern reptiles, they likely hatched from eggs and underwent significant growth stages, a far cry from the monolithic images previously conjured.

The implications of this find rippled through the nascent field of paleontology. It allowed scientists to compare the juvenile specimen with adult fossils, tracing the evolutionary path and developmental stages of this ancient mariner. The differences in bone structure and size between the young and old Plesiosaurus provided invaluable data for understanding growth patterns and variations within the species. It offered a more nuanced picture of Jurassic ecosystems, revealing that these seas weren’t just populated by adult behemoths, but also by their young, vulnerable offspring, navigating the same dangerous waters.

Little did Anning and her contemporaries know how profoundly this single discovery would shape our understanding of marine reptile evolution. The juvenile Plesiosaurus became a symbol of the intricate life cycles that played out in Earth’s ancient oceans. It underscored the importance of finding fossils across different life stages to build a comprehensive picture of extinct species. This find wasn’t just about a single creature; it was about understanding growth, adaptation, and the rich tapestry of life that existed long before humans walked the Earth. It proved that even the smallest fossil can hold the power to reshape our perception of the past, reminding us that history is not just made by the giants, but also by the little ones who grew to be them.