Imagine this: the sweltering heart of summer in 64 AD, Rome, a city teeming with life, a sprawling metropolis of marble and timber, of bustling marketplaces and opulent palaces. The air, thick with the scent of baking bread, sweat, and the exotic spices carried on trade routes, was about to be irrevocably tainted by the acrid stench of smoke.

Our story begins on a fateful night, the 19th of July, 64 AD. The flames first flickered to life in the merchant district surrounding the Circus Maximus, a vast arena where crowds had gathered for games. It was a tinderbox waiting for a spark. Dry, hot weather, coupled with the densely packed wooden structures of the city, provided the perfect conditions for a catastrophe. The fire, catching hold with terrifying speed, became an inferno, a ravenous beast consuming everything in its path.

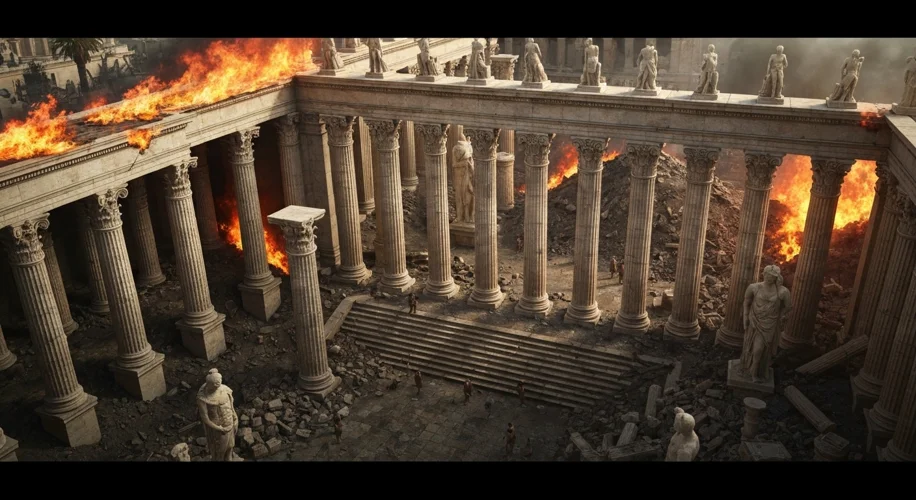

The fire raged for six days and seven nights, a relentless tide of destruction. It swept through narrow alleyways, leapt across streets, and devoured entire neighborhoods. The magnificent temples, the grand public buildings, the humble abodes of the common folk – all were reduced to smoldering ruins. The cries of the terrified populace mingled with the roar of the flames, a symphony of despair echoing through the ash-choked air.

As the smoke began to clear and the extent of the devastation became agonizingly clear, a question hung heavy in the Roman air: who was responsible? Suspicion quickly fell upon Emperor Nero. Rumors, fueled by fear and uncertainty, painted a grim picture of the emperor fiddling while Rome burned, or worse, orchestrating the destruction himself. Tacitus, a Roman historian writing decades later, recounts the tale of Nero gazing upon the burning city from his palace tower, supposedly inspired to compose a song about the sack of Troy. While the accuracy of this dramatic image is debated, the perception of Nero as callous, even culpable, took root.

But Nero, a shrewd and often paranoid ruler, needed a scapegoat. His gaze turned towards a nascent and misunderstood religious sect: the Christians. They were a minority group, often viewed with suspicion and hostility by the Roman populace due to their unusual practices and their refusal to worship Roman gods. Nero, according to the historian Suetonius, seized upon this simmering prejudice. He publicly accused the Christians of arson, using them as a convenient diversion from the whispers of his own involvement.

The consequences for the Christians were horrific. They were subjected to brutal punishments. Some were thrown to wild beasts in the arena, others were crucified, and a particularly gruesome form of execution involved being coated in pitch and set alight to serve as human torches for Nero’s nocturnal gardens. This period marked one of the first major persecutions of Christians within the Roman Empire, a tragic testament to the brutal realities of political scapegoating.

The fire, however, was not entirely without its positive outcomes for Rome, albeit born from tragedy. Nero, perhaps to quell further unrest or to fulfill a genuine desire to rebuild, initiated a massive reconstruction program. New building codes were introduced, mandating wider streets, the use of stone rather than timber in construction, and ensuring buildings had adequate space between them to prevent the rapid spread of fire. Many historians believe Nero’s subsequent rebuilding efforts, including the construction of his opulent Golden House (Domus Aurea), were influenced by the fire, shaping the city’s future landscape.

The Great Fire of Rome remains a pivotal event in history, shrouded in a mixture of verifiable fact and enduring legend. It serves as a stark reminder of the vulnerability of even the grandest cities to the forces of nature and human error. More significantly, it highlights the destructive power of unchecked political ambition and the devastating consequences of scapegoating marginalized communities. The fire not only reshaped the physical landscape of Rome but also indelibly marked the historical narrative of Christianity, setting a precedent for future persecutions and forging a powerful narrative of martyrdom that would resonate for centuries to come. The ashes of Rome in 64 AD carried the weight of lost lives, shattered dreams, and a chilling premonition of the trials that lay ahead for a fledgling faith.