Imagine a time before written laws, where justice was as fluid as the desert sands, decided by the whims of rulers or the strength of one’s arm. Now, picture a stark stone stele, nearly eight feet tall, rising from the heart of Mesopotamia. Carved into its surface, in crisp cuneiform script, are over 280 laws, a revolutionary attempt to bring order and predictability to a complex society. This is the legacy of Hammurabi, the sixth king of Babylon, and his monumental Code of Laws, established around 1754 BCE.

Before Hammurabi, laws were often unwritten, passed down through oral tradition, making them susceptible to interpretation and abuse. Babylonian culture, like many ancient civilizations, was deeply hierarchical. Society was divided into distinct classes: the free citizens (awilum), the dependants (mushkenum), and slaves (wardum). Each group had different rights and responsibilities, and the Code of Hammurabi, while a step towards codified justice, certainly reflected these social stratifications.

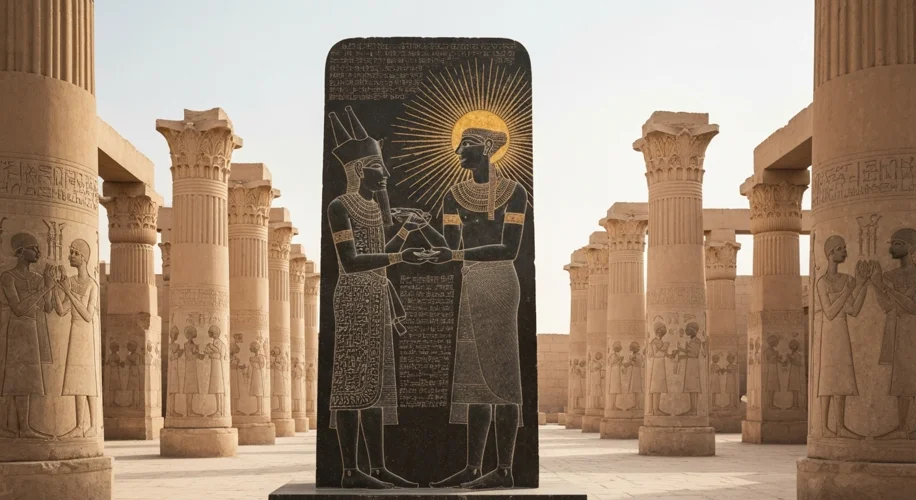

Hammurabi himself was no mere figurehead. He was a skilled administrator and a conqueror who transformed Babylon from a minor city-state into a dominant empire stretching across much of Mesopotamia. His ambition was not just military, but also administrative. He saw the need for a unified legal system to govern his vast and diverse kingdom, ensuring stability and the king’s authority.  The stele itself is a testament to the importance Hammurabi placed on his laws. At its apex, Hammurabi is depicted receiving the laws from Shamash, the Babylonian god of justice. This divine endorsement was crucial, lending an air of unassailable authority to the code. It wasn’t just the king’s decree; it was the will of the gods, made manifest.

The stele itself is a testament to the importance Hammurabi placed on his laws. At its apex, Hammurabi is depicted receiving the laws from Shamash, the Babylonian god of justice. This divine endorsement was crucial, lending an air of unassailable authority to the code. It wasn’t just the king’s decree; it was the will of the gods, made manifest.

The Code of Hammurabi is famed for its principle of lex talionis, often summarized as “an eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth.” For instance, Law 196 states, “If a man put out the eye of another man, his eye shall be put out.” However, this principle was not applied universally. The severity of the punishment often depended on the social status of both the perpetrator and the victim. If a nobleman struck a man of lower status, the penalty might be a fine rather than physical retribution. Conversely, if a commoner struck a nobleman, the punishment would be far more severe than a simple fine.

The laws covered a wide range of societal issues: property rights, trade, family law (marriage, divorce, inheritance), assault, theft, and even medical malpractice. For example, Law 229 stipulated that if a builder constructed a house that collapsed and killed the owner, the builder would be put to death. This highlights a direct accountability that might seem harsh by modern standards, but it speaks to the era’s emphasis on consequences and the protection of property and life.

The impact of the Code of Hammurabi was profound and far-reaching. It provided a consistent framework for justice, reducing arbitrary rulings and establishing a precedent for written legal systems. It helped to solidify Hammurabi’s rule and fostered a sense of order within his empire. While certainly not a perfect embodiment of modern justice – its punishments were often brutal, and it was deeply influenced by social hierarchy – it was a monumental step forward. It demonstrated a sophisticated understanding of the need for a predictable legal system to govern a complex society.

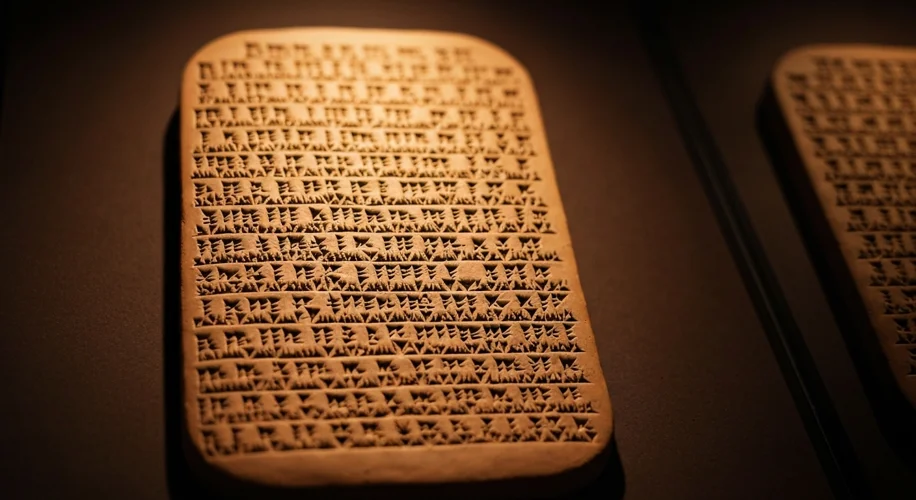

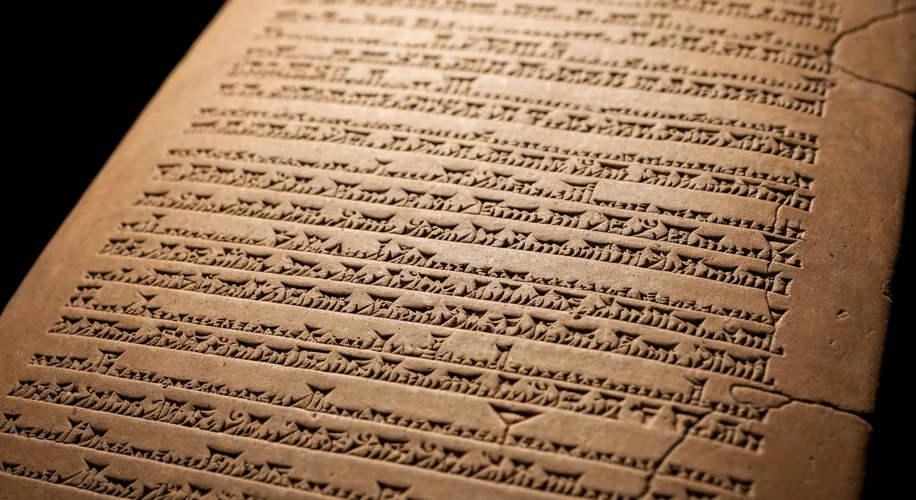

What makes the Code of Hammurabi so compelling today is its window into the ancient world’s values, priorities, and understanding of justice. It reveals a society grappling with fundamental questions: how to ensure fairness, protect the vulnerable (within limits), and maintain social order. It wasn’t just about punishment; it was about establishing societal norms and expectations. The very act of inscribing these laws onto stone ensured their permanence and accessibility, a powerful statement of intent.

In essence, the Code of Hammurabi stands as a foundational text in the history of law. It represents humanity’s early, albeit imperfect, quest to codify justice, to move from the rule of man to the rule of law, and to build societies on a bedrock of established principles, however ancient and alien they may seem to us now.