Picture this: vast armies on horseback, their hooves thundering across the steppes, a constant, menacing shadow on the northern horizon. For centuries, this was the reality for the fragmented states and later, the unified empires of China. These weren’t mere border skirmishes; these were existential threats, waves of nomadic warriors like the Xiongnu, the Mongols, and others, seeking plunder and conquest.

But China did not crumble. Instead, it began to build. Not a single, monolithic structure, but a colossal, evolving defense system – the Great Wall. This isn’t the smooth, brick-faced marvel we often see in photographs; the Wall is a patchwork quilt of history, a testament to the ingenuity, labor, and sheer will of countless generations.

The story of the Great Wall doesn’t begin with a single emperor or a grand unveiling. Its roots stretch back to the Spring and Autumn (771-476 BCE) and Warring States (475-221 BCE) periods. Here, individual states, vying for survival and dominance, began constructing their own earthen ramparts and fortifications. Think of these as the Wall’s scattered, early ancestors, built with rammed earth, timber, and stone, forming rudimentary barriers against rival states and northern raiders.

The true genesis of the Wall as a unified concept, however, arrived with Qin Shi Huang, the First Emperor of China, who unified the nation in 221 BCE. Fresh from conquering his rivals, he ordered the connection and extension of existing walls, creating a more cohesive defense against the Xiongnu confederation that threatened his new empire. Imagine the sheer scale of this undertaking: hundreds of thousands of laborers, including soldiers, peasants, and convicts, toiling under harsh conditions. They moved earth and stone, constructing watchtowers and fortifications along a massive front. The air, we can imagine, hung heavy with the dust of construction, the cries of overseers, and the silent endurance of those who built it.

Yet, the Qin dynasty’s wall was not the final word. Subsequent dynasties, each facing their own northern threats, contributed to, rebuilt, and expanded upon the existing structures. The Han Dynasty (206 BCE – 220 CE) extended the Wall westward to protect the lucrative Silk Road trade routes. The Northern Wei, Northern Qi, and Northern Zhou dynasties (4th-6th centuries CE) all engaged in significant construction and repair.

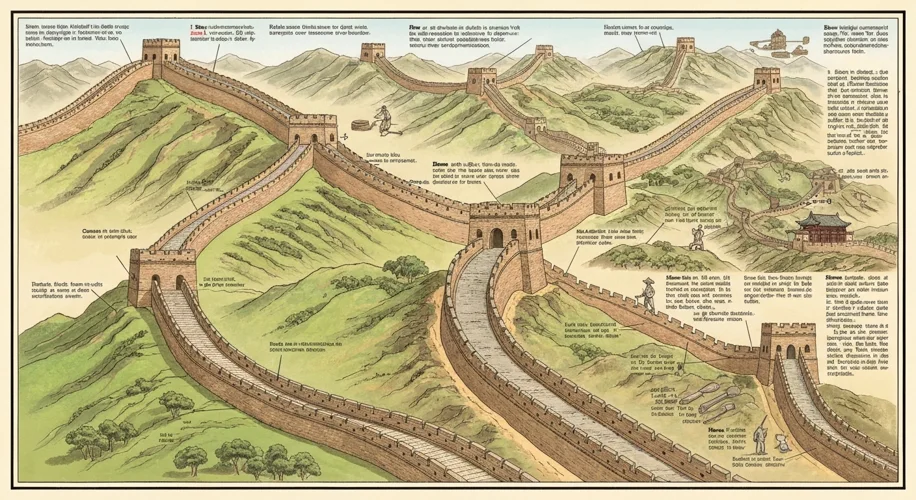

The most recognizable and enduring sections of the Great Wall, however, hail from the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644 CE). Facing renewed threats from the Mongols and later the Manchus, the Ming emperors invested heavily in its construction. This era saw the widespread use of stone and brick, creating the formidable, crenellated battlements and imposing watchtowers that have become iconic. These weren’t just walls; they were sophisticated military installations, designed to house troops, store supplies, and provide elevated platforms for archery and cannon fire. The sheer manpower required for the Ming construction was staggering, involving millions of laborers over centuries.

The Great Wall was more than just a physical barrier; it was a symbol of Chinese civilization, a demarcation line between the settled agricultural society of China and the nomadic cultures of the steppes. It dictated trade routes, influenced military strategy, and became deeply ingrained in the Chinese psyche. For the ordinary soldier stationed on its remote battlements, life was a mix of grueling duty, constant vigilance, and perhaps a profound sense of isolation, staring out at the vast, untamed lands beyond.

Little did they know, these seemingly endless efforts would ultimately create one of the most recognizable human-made structures on Earth. The Great Wall, in its fragmented, evolving glory, stands as a monumental testament to human perseverance, the complex interplay of cultures, and the enduring desire for security. It’s a story etched in stone, earth, and the sweat of millions, a silent, colossal dragon guarding the heart of China for millennia.