Imagine the roar of the crowd, a deafening wave of anticipation crashing against the stone. Dust motes dance in the shafts of Roman sunlight, illuminating the sand-covered arena below. On one side, a gladiator, sweat glistening on his bronzed skin, grips his sword, the weight of the empire’s gaze upon him. On the other, a lion paces, its magnificent mane framing eyes that hold the primal fury of the wild.

This was the stage for the Flavian Amphitheatre, known to us today as the Colosseum, a monument that rose from the ashes of Nero’s tyrannical reign to become the beating heart of Roman entertainment and a potent symbol of imperial might. Completed in 80 AD, this colossal structure was not merely a building; it was a statement, a meticulously engineered marvel designed to awe, distract, and control the vast populace of Rome.

The story of its construction is as dramatic as the spectacles it housed. Following the Great Fire of Rome in 64 AD and the subsequent suicide of Emperor Nero, the city was in turmoil. Nero’s Golden House, an opulent palace complex, occupied a vast area of the city center, including a man-made lake. Emperor Vespasian, founder of the Flavian dynasty, ascended to power with a mission to restore order and public trust. What better way to achieve this than to reclaim the land Nero had privatized for himself and gift it back to the Roman people in the form of a grand public amphitheater?

The vision was audacious. Vespasian initiated the project, drawing on the spoils of the Jewish War, including treasures plundered from the Temple in Jerusalem. His son, Titus, saw it through to completion, inaugurating it with 100 days of games. The sheer scale of the undertaking was staggering. Tens of thousands of laborers, many likely slaves and prisoners of war, toiled for years. Architects and engineers devised innovative methods to construct a building of unprecedented size and complexity, capable of holding an estimated 50,000 to 80,000 spectators.

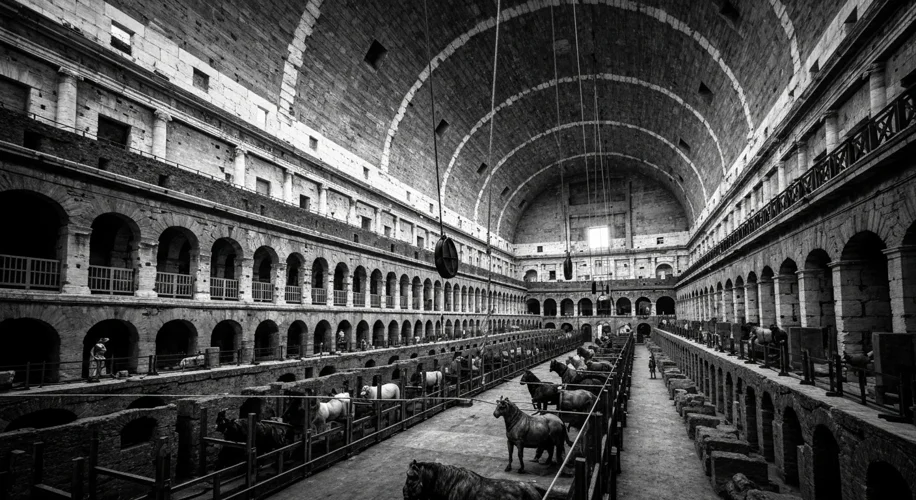

Crafted from travertine limestone, tuff, and brick-faced concrete, the Colosseum was a masterpiece of Roman engineering. Its elliptical shape and tiered seating ensured excellent visibility for all attendees. A complex system of arches and vaults supported the massive structure, while underground, a labyrinthine network of tunnels and chambers known as the hypogeum housed gladiators, wild animals, and the elaborate machinery used to hoist them onto the arena floor. Imagine the tension building as a trapdoor opened, revealing a roaring beast or a determined warrior.

The spectacles held within these walls were legendary. Gladiator combats, often fought to the death, were the main draw. But the Colosseum also hosted venationes (wild animal hunts), public executions, and even naumachiae, or mock sea battles, for which the arena floor was flooded. These events were not just entertainment; they were carefully orchestrated displays of Roman power, showcasing exotic animals from across the empire and the dominion Rome held over both man and beast.

For the ordinary Roman, the Colosseum offered a potent escape from daily life. It was a place where social hierarchies were momentarily blurred, with seating arranged according to social status, from the emperor and senators in the prime lower tiers to the commoners and women in the upper reaches. The games were a form of panem et circenses – bread and circuses – a strategy to keep the populace content and distracted from political or economic hardships.

However, the Colosseum’s legacy is not solely one of brutal entertainment. It stands as a testament to Roman ingenuity, architectural prowess, and the sheer organizational capacity of the empire. It was a space that reflected the values, ambitions, and even the anxieties of Roman society. While gladiatorial combat eventually ceased with the rise of Christianity and changing social mores, the Colosseum endured, a silent witness to centuries of history.

Today, as we gaze upon its magnificent ruins, the Colosseum continues to evoke a sense of awe. It reminds us of a civilization that could build such a colossal structure, stage such grand and often gruesome spectacles, and wield power on a scale that shaped the Western world. It is more than just an ancient ruin; it is an echo of the past, a powerful reminder of Rome’s enduring legacy and the captivating, complex story of human ambition and entertainment.

What can we learn from this monumental arena? Perhaps it’s a lesson in the power of public spectacle, the intricacies of societal control, or the sheer enduring spirit of human creativity and engineering. The Colosseum, even in its ruined state, continues to speak volumes.