In the quiet scriptoriums of medieval England, monks toiled, not just to record the deeds of kings and the ebb and flow of battles, but to weave the tapestry of human history into a grand, divinely ordained narrative. Among the most remarkable of these efforts is the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, a vernacular history that, in its early passages, reveals a fascinating, and perhaps surprising, approach to chronology: a remarkably condensed lineage from a prominent Anglo-Saxon king all the way back to Noah.

Imagine a scholar in the 9th century, tasked with understanding humanity’s place in the cosmos. Their worldview was profoundly shaped by the Bible, the ultimate authority on all matters, including history. The creation of the world, the great flood, and the subsequent repopulation of the Earth were not abstract theological concepts but historical facts. To these medieval minds, history was a linear progression, a divine plan unfolding from Genesis to the present day, with every king and nation occupying a divinely appointed slot within this grand scheme.

This is where King Æthelwulf of Wessex, father of Alfred the Great, enters the picture. Æthelwulf, who reigned in the 9th century, was a significant figure in the consolidation of Anglo-Saxon power. His reign was marked by both military campaigns against the Vikings and significant religious devotion, even undertaking a pilgrimage to Rome. However, it is his inclusion in the Chronicle‘s genealogical account that offers a peculiar window into medieval chronological thinking.

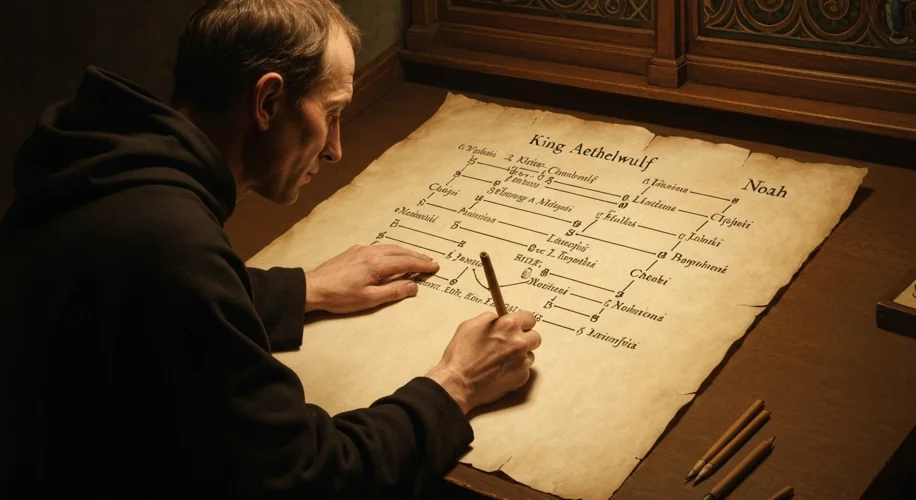

Consider the early entries of the Chronicle. It aims to establish a continuous historical thread, linking the Anglo-Saxons to the biblical patriarchs. The challenge for the scribes was to bridge the vast expanse of time between their own era and the events described in the Old Testament. They relied on biblical genealogies, often interpreting them with a certain flexibility that might seem jarring to modern historians. For instance, the Chronicle meticulously traces lineage, but the number of generations between a given king and a biblical figure could be remarkably few.

Let’s focus on the lineage from Æthelwulf back to Noah. In some versions of the Chronicle, the generations listed between Æthelwulf and Noah are surprisingly sparse. While a literal, year-by-year calculation based on the ages provided in Genesis might suggest a much longer span, the Chronicle often presents a more streamlined genealogy. This wasn’t necessarily due to poor mathematical skills or ignorance of the biblical texts. Instead, it reflected a different understanding of historical time and genealogical transmission. Medieval chroniclers often focused on key figures, assuming significant, but unrecorded, generational links, or sometimes, a more symbolic representation of descent rather than a strictly literal one.

This approach allowed them to maintain the biblical narrative as the ultimate framework for all subsequent history. If a king could be directly linked, however briefly, to the patriarchs, it validated his rule and his people’s place in God’s plan. It was a way of asserting legitimacy and connecting their relatively new kingdom to the most ancient and sacred of histories.

The implications of this condensed timeline are profound. It reveals a worldview where faith and history were inextricably intertwined. The Bible was not just a religious text; it was the foundational history book. The scribes were not merely recording events; they were participating in a sacred act of historical curation, aligning earthly kingdoms with the celestial order.

Furthermore, it highlights the medieval concept of “deep time” as understood through a theological lens. While we today grapple with geological and cosmic timescales, medieval scholars understood deep time through the lens of salvation history, beginning with creation and culminating in the Last Judgment. The generations between Æthelwulf and Noah, though compressed in the Chronicle, still represented an immense, divinely sanctioned antiquity.

This condensed genealogy from Æthelwulf to Noah serves as a compelling reminder of how different cultures and eras conceptualize time, lineage, and the very nature of historical truth. It invites us to look beyond the specific numbers and appreciate the underlying worldview – one where faith provided the ultimate chronology, and every earthly kingdom found its place within a narrative stretching back to the dawn of creation and the survivors of the great flood.

So, the next time you encounter the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, remember the meticulous work of those monks. They weren’t just chronicling events; they were building a bridge, however surprisingly short, from the heart of Anglo-Saxon England to the very beginning of human history as they understood it.