For over a millennium and a half, the Chrysanthemum Throne has sat at the pinnacle of Japanese society. But what lies beneath the gilded surface of this ancient institution? The prevailing narrative, etched into the very foundation of Japanese historical consciousness, claims an unbroken lineage stretching back to the sun goddess, Amaterasu-Omikami. This divine ancestry, meticulously documented in the eighth-century chronicles Kojiki and Nihon Shoki, was not merely a pious belief; it was a potent political tool, a bedrock upon which imperial authority was built and defended.

The Kojiki (Record of Ancient Matters) and the Nihon Shoki (The Japan Chronicles) are more than just historical texts; they are foundational myths, woven with the threads of Shinto cosmology and the ambitions of a nascent state. Compiled during a period of immense political flux in the Nara period (710-794 CE), these works sought to legitimize the ruling Yamato clan’s dominance over a fragmented Japan. They presented a sweeping narrative, beginning with the creation of the islands by divine beings and culminating in the descent of the first human emperor, Jimmu, from Amaterasu. This celestial mandate was the ultimate credential, asserting that the Emperor was not just a ruler, but a living god, a direct descendant of the most powerful kami (deity) in the Shinto pantheon.

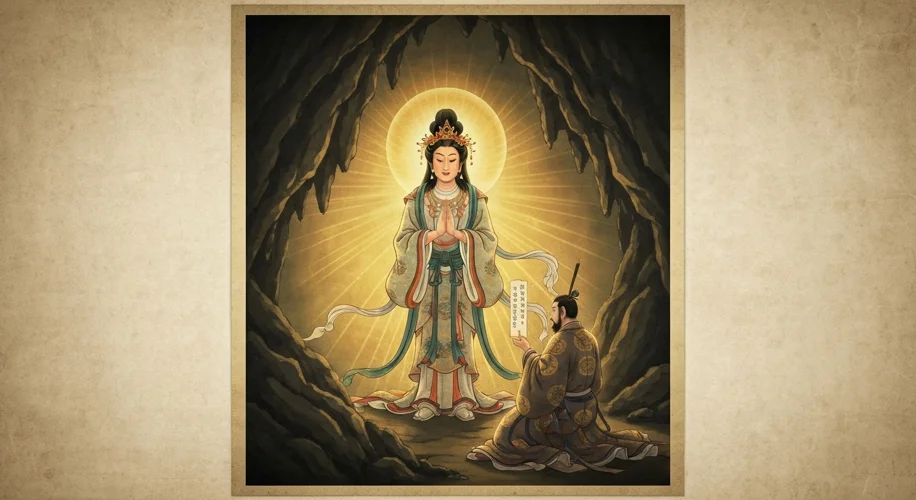

The narrative was compelling: Amaterasu, offended by her brother Susanoo, hid in a cave, plunging the world into darkness. The other kami devised a plan to lure her out, featuring music, dance, and the revelation of a mirror. This story, when linked to the imperial line, transformed the Emperor into the embodiment of the sun’s life-giving power, essential for the prosperity and order of the nation. The Nihon Shoki, in particular, with its more overt political agenda, meticulously crafted genealogies and historical accounts to reinforce this divine connection, ensuring that the Emperor’s claim to legitimacy was unassailable.

But the imperial line was not the only powerful entity in ancient Japan. Other aristocratic families, such as the Soga, Fujiwara, and Tachibana clans, also wielded considerable influence. As they vied for power and prestige, some of these powerful families, while perhaps not directly claiming divine descent for themselves in the same way as the Imperial house, certainly sought to associate their own lineages with the divine. They might achieve this by marrying into the imperial family, thus gaining proximity to divinity, or by patronizing powerful shrines and priesthoods, thereby absorbing some of the sacred aura of the Shinto deities. The Fujiwara clan, for instance, dominated court politics for centuries, often ruling as regents for emperors, and their historical accounts would naturally emphasize their crucial role in supporting and advising the divinely appointed ruler.

Consider the case of the Soga clan. They rose to prominence in the 6th century, wielding significant power and even introducing Buddhism to Japan, a move that sometimes put them at odds with the traditional Shinto establishment. While their primary claims to power were rooted in political maneuvering and wealth, their historical influence meant they were inextricably linked to the imperial narrative. Their biographies and the accounts of their deeds, as recorded in later chronicles, would inevitably frame their actions within the context of serving the imperial line, a subtle way of reinforcing their own status through association with the divine mandate.

The strategic deployment of divine ancestry was a recurring theme in the establishment of monarchies worldwide. However, in Japan, the unbroken, unbroken claim to descent from a specific, powerful deity like Amaterasu provided a unique and enduring foundation for the imperial institution. This wasn’t just about proclaiming a superior bloodline; it was about imbuing the ruler with sacred authority, making rebellion against the Emperor akin to defying the heavens themselves. This theological-political pact between the ruler and the divine sustained the imperial house through centuries of change, including the rise of the samurai class and the establishment of shogunates, where practical power often lay elsewhere, but the symbolic and spiritual authority of the Emperor, rooted in his divine descent, remained paramount.

Even as Japan modernized in the Meiji era (1868-1912), the imperial lineage was re-emphasized as the unifying force of the nation. The Emperor Meiji was presented as the direct descendant of Jimmu, and therefore of Amaterasu, a sacred figurehead for a rapidly transforming country. This divine connection provided a potent ideological anchor, fostering national unity and loyalty during a period of immense upheaval and westernization. The myth, meticulously crafted and consistently reinforced through state-sponsored narratives and religious practices, proved to be an incredibly resilient pillar of Japanese identity and political structure, demonstrating the enduring power of divine claims in shaping dynastic legitimacy.