The sleek iPhone in your pocket, the familiar glow of your laptop screen – these digital marvels didn’t appear overnight. They are the culmination of decades of innovation, a journey that began with clunky machines and a revolutionary idea: putting computing power into the hands of ordinary people.

For much of the 20th century, computers were behemoths, confined to laboratories and corporations. Think vast rooms filled with whirring tapes, blinking lights, and armies of engineers. These were “mainframes,” accessible only to a privileged few. But a seismic shift was brewing in the late 1970s, a movement that would democratize technology and forever alter the fabric of our lives.

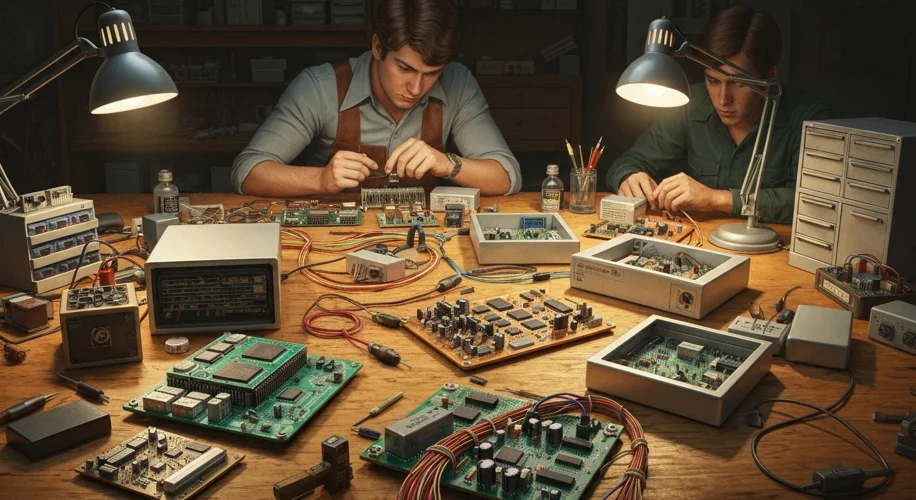

The spark ignited in garages and basements, fueled by a passion for electronics and a vision of what could be. In 1975, the Altair 8800, a kit computer, hit the market. It was primitive, requiring users to input commands using switches and interpret output via blinking lights. Yet, it captivated a generation of hobbyists, including two young men named Bill Gates and Paul Allen. Recognizing the potential of software to unlock the power of these new machines, they founded Microsoft, initially developing a BASIC interpreter for the Altair.

Meanwhile, in California, Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak were building something more user-friendly. Their Apple II, released in 1977, was a game-changer. Unlike the Altair, it came pre-assembled, featured a color display, and could be programmed with relative ease. It was designed not just for the electronics enthusiast, but for the home user, the student, and the small business owner. The Apple II was a runaway success, laying the groundwork for a burgeoning industry.

But hardware is only half the story. To make these machines truly useful, they needed intelligent software to manage their operations – an operating system (OS). Early personal computers often used rudimentary command-line interfaces, where users typed specific commands to interact with the machine. This was functional, but hardly intuitive.

Microsoft’s big break came with MS-DOS (Microsoft Disk Operating System), licensed to IBM for its groundbreaking Personal Computer (PC) launched in 1981. The IBM PC, with its open architecture, quickly became the standard, and MS-DOS, despite its text-based limitations, powered millions of machines. It was a system built on efficiency, but it demanded a certain level of technical understanding.

The true revolution in user interaction, however, was brewing at Xerox PARC (Palo Alto Research Center). Researchers there had developed the concept of a Graphical User Interface (GUI), featuring windows, icons, and a mouse-driven pointer. This visual approach promised to make computers accessible to everyone, regardless of their technical skill.

Steve Jobs famously visited Xerox PARC and was inspired by these advancements. He saw the potential to bring this revolutionary interface to the masses. This vision materialized in the Apple Lisa in 1983 and, more significantly, the Apple Macintosh in 1984. The Macintosh, with its iconic “1984” Super Bowl commercial, introduced the world to a user-friendly, mouse-driven experience that would redefine personal computing. Suddenly, interacting with a computer felt less like speaking a secret code and more like navigating a familiar desktop.

As the 1980s progressed, the battle for operating system dominance intensified. Microsoft, initially focused on MS-DOS, eventually developed Windows, a GUI that ran on top of MS-DOS. Early versions of Windows were functional but still felt like an add-on. However, Windows 3.0 in 1990 marked a turning point, offering a more stable and visually appealing experience that began to seriously challenge the Macintosh.

This era was marked by intense competition and rapid innovation. Companies like Commodore, with its Amiga, and Atari also contributed significantly to the early personal computer landscape, often pushing boundaries in graphics and multimedia. The development of operating systems like AmigaOS, with its preemptive multitasking and advanced graphics capabilities, showcased alternative paths the industry could have taken.

The legacy of these early operating systems is profound. They laid the foundation for everything we do today. MS-DOS, with its command-line efficiency, proved the power of a robust software backbone. The Macintosh introduced a paradigm shift in human-computer interaction with its GUI, making computing accessible and intuitive. Windows, evolving from its DOS roots, ultimately brought graphical interfaces to the mainstream PC market.

From the intricate dance of punch cards to the fluid swipe of a touchscreen, the journey of personal computing and its operating systems is a testament to human ingenuity. It’s a story of visionaries who dared to dream of a world where technology empowers everyone, a story that continues to unfold with every software update, every new device, and every digital interaction.