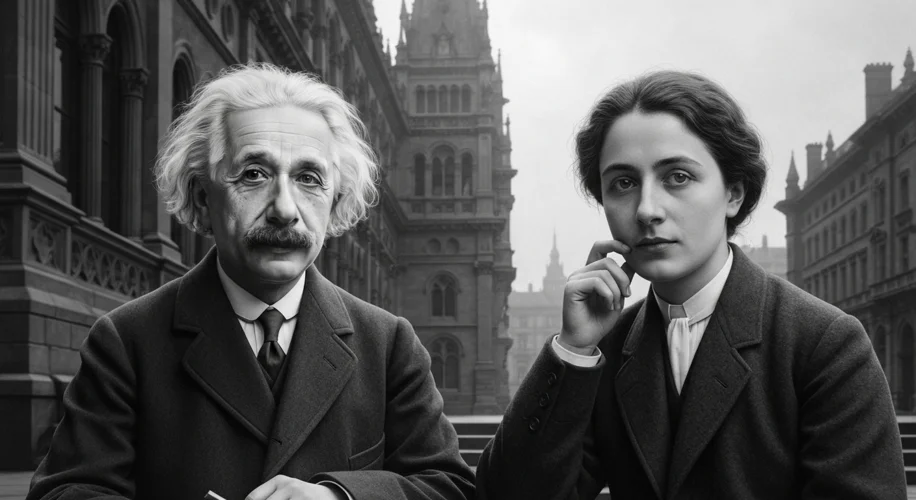

In the hallowed halls of physics, the name Albert Einstein reverberates with an almost mythic resonance. His theories of relativity, the photoelectric effect, and the mass-energy equivalence (E=mc²) fundamentally reshaped our understanding of the universe. Yet, whispered in the corridors of scientific history, a tantalizing question lingers: to what extent did his first wife, Mileva Marić, contribute to the intellectual scaffolding that supported his monumental achievements?

Born in 1875 in the Austro-Hungarian Empire, Mileva Marić was a woman of exceptional intellect in an era that largely confined women to domestic spheres. She excelled in mathematics and physics, eventually enrolling at the Zurich Polytechnic (now ETH Zurich) in 1896, the same year and institution where a young Albert Einstein would also begin his studies. They were among the very few women in a male-dominated academic world, forging a bond over their shared passion for science. Their early correspondence reveals a deep intellectual connection, filled with discussions of physics and mathematics, often interspersed with affectionate banter.

The most compelling evidence for Marić’s potential contribution lies in their collaborative efforts during their courtship and early marriage. Before the groundbreaking papers of 1905 – Einstein’s “annus mirabilis” (miracle year) – their letters suggest a partnership. For instance, in a letter from March 1901, Einstein writes, “I am now hard at work on my paper on the thermal equilibrium of radiation and on the electrodynamics of moving bodies. I am very glad you are working on the same subjects.”

This statement, alongside other letters where Einstein refers to “our work” or “our theory,” has fueled speculation. Did “our work” signify a genuine collaboration, a co-authorship in all but name? The debate centers on how much of the early conceptualizations and mathematical rigor can be attributed to Marić. Some historians point to her advanced studies and the intellectual environment they shared, suggesting she provided crucial insights or even helped refine Einstein’s complex mathematical formulations.

However, definitive proof of her direct authorship in the published papers remains elusive. The papers themselves are solely credited to Albert Einstein. This lack of formal recognition has led to various interpretations. Was Marić a silent partner, overshadowed by her brilliant husband? Did societal constraints and the prevailing attitudes towards women in science prevent her from claiming her due? Or was Einstein the primary innovator, with Marić as a supportive and intellectually engaged companion?

The personal dimension of their relationship adds another layer to this intricate narrative. They married in 1903 and had three children. Their life together was marked by financial struggles and later, by marital discord, exacerbated by Einstein’s growing fame and his affair with his cousin Elsa, whom he eventually married after divorcing Mileva. In the divorce settlement, Marić received a portion of Einstein’s Nobel Prize money, a detail that some interpret as an acknowledgement of her intellectual contributions.

The “Einstein-Marić” debate is complex, involving interpretations of personal letters, historical context, and the very nature of scientific collaboration. Scholars like Senta German and Abraham Pais have explored these themes, with varying conclusions. Some argue forcefully for Marić’s significant, albeit uncredited, role, citing her scientific aptitude and the collaborative tone of their early correspondence. Others maintain that while their intellectual exchange was vital, the ultimate conceptual breakthroughs and the writing of the papers were Einstein’s alone.

One compelling argument for Marić’s contribution comes from Eva, Einstein’s son, who reportedly stated that his mother helped with his father’s work. However, the reliability and context of such statements are often debated.

Regardless of the precise extent of her direct contribution to specific papers, Mileva Marić’s story is a poignant reminder of the countless women whose intellectual endeavors may have been subsumed by the dominant narratives of history. Her life underscores the systemic barriers women faced in pursuing scientific careers in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Even as a student at Zurich Polytechnic, she was exceptional, a rarity in a field dominated by men.

Ultimately, Mileva Marić remains an enigmatic figure. Was she the hidden architect of some of the most profound scientific ideas of the 20th century, a genius whose light was deliberately or inadvertently dimmed by the glare of her famous husband? Or was she a brilliant woman who found intellectual solace and partnership in a shared journey with Einstein, a journey that ultimately led him to explore the universe in ways no one had before? The answer may never be definitively known, but the questions surrounding her legacy continue to illuminate the often-unseen contributions of women in the grand tapestry of scientific discovery.

The debate over Mileva Marić’s role in Albert Einstein’s early work continues to spark fascination, prompting a re-examination of how scientific credit is assigned and how societal structures can influence the recognition of intellectual contributions. Her story compels us to look beyond the celebrated names and consider the collaborative spirit, and perhaps the silenced voices, that often lie at the heart of groundbreaking discoveries.