In the tumultuous 17th and 18th centuries, amidst the sprawling empires of Eastern Europe, a unique bastion of autonomy flickered into existence: the Cossack Hetmanate. This wasn’t just a military force; it was a nascent state, a testament to Ukrainian aspirations for self-determination, forged in the crucible of constant conflict.

The story begins with the Zaporozhian Sich, a semi-military, semi-communal brotherhood nestled on the islands of the Dnieper River. These were the Cossacks – formidable warriors, fiercely independent, and a constant thorn in the side of their nominal overlords, the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. The Commonwealth, a vast and complex entity, often viewed its Ukrainian subjects, particularly the Orthodox clergy and peasantry, with suspicion, imposing policies that stoked resentment.

The simmering discontent erupted in 1648 with the great Khmelnytsky Uprising, led by Hetman Bohdan Khmelnytsky. Khmelnytsky, a nobleman and a seasoned military commander, galvanized the Ukrainian populace – peasants, burghers, and even some dissatisfied nobility – against Polish rule. His vision was clear: an autonomous Ukraine, free from the religious and political oppression of the Commonwealth. The initial years of the uprising were marked by stunning Cossack victories, pushing Polish forces back and establishing a de facto state centered around the Hetmanate.

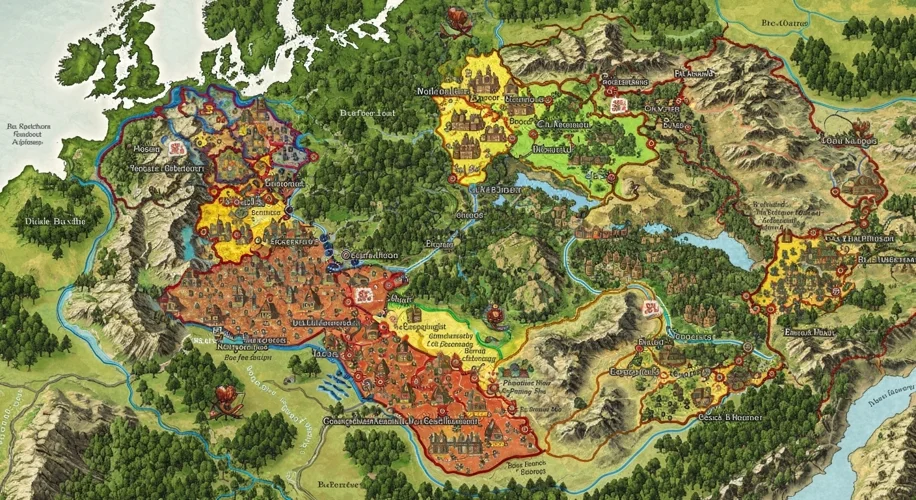

The Hetmanate, though initially a military camp, quickly evolved into a more structured administration. Cities like Chyhyryn became its capital, and a sophisticated military and administrative hierarchy emerged. However, its existence was precarious. Surrounded by powerful neighbors, the Hetmanate found itself in a diplomatic tightrope walk. Khmelnytsky, seeking a powerful ally to secure his gains, turned to Tsar Alexis of Russia. The Treaty of Pereyaslav in 1654, though interpreted differently by both sides, marked a pivotal moment – an agreement for Russian protection that would ultimately lead to Moscow’s increasing influence over Ukrainian affairs.

The period that followed was a chaotic tapestry of shifting alliances and brutal warfare. The Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, weakened but not broken, sought to reassert its control. Russia, now entangled, expanded its dominion. The Cossack Hetmanate became a battleground, caught between these colossal powers. Internal divisions also plagued the Cossacks, with rival factions often aligning with different foreign powers, leading to devastating civil wars known as the “Ruin.”

Despite the internal strife and external pressures, the Hetmanate managed to preserve a significant degree of autonomy for much of the late 17th and early 18th centuries. Figures like Hetman Ivan Mazepa, a patron of arts and a staunch defender of Cossack rights, attempted to steer a course independent of Russia. Mazepa famously allied with Sweden’s King Charles XII against Peter the Great of Russia, a gamble that ended in defeat at the Battle of Poltava in 1709. This defeat severely curtailed Ukrainian autonomy and marked a turning point in Russian imperial policy.

Over time, the Tsardom of Russia gradually eroded the Hetmanate’s self-governance. Catherine the Great, in particular, systematically dismantled its institutions. The last vestiges of Cossack autonomy were abolished in the late 18th century, effectively integrating the Hetmanate into the Russian Empire. The vibrant period of Ukrainian self-rule, though extinguished, left an indelible mark on the Ukrainian national consciousness.

The legacy of the Cossack Hetmanate is complex. It represents a crucial, albeit ultimately unfulfilled, chapter in Ukraine’s long struggle for statehood. It was a time of immense military prowess, cultural flourishing, and fierce independence. The Cossacks, with their distinctive dress, their battle cries, and their unwavering spirit, became potent symbols of Ukrainian identity. Their story serves as a powerful reminder of the enduring desire for self-determination that has shaped Ukraine’s history and continues to resonate today.