In a world defined by borders and territories, maps are our silent guides, shaping our understanding of geography and, by extension, our perception of nations and peoples. Yet, what if these seemingly objective tools carry an inherent bias, a distortion that has influenced global perspectives for centuries? Enter the Mercator projection, a cartographic marvel born in the 16th century, whose legacy is as complex as the globe it attempts to represent.

Gerardus Mercator, a Flemish cartographer, unveiled his innovative world map projection in 1569. His goal was practical: to create a navigational chart where compass lines—rhumb lines—appeared as straight segments, greatly aiding sailors in plotting their courses across vast, uncharted oceans. The mathematical genius behind it was a clever transformation of the spherical Earth onto a flat surface, a cylindrical projection where lines of latitude and longitude intersect at right angles. This made directions and distances relatively consistent at any point on the map, a revolutionary feat for the Age of Discovery.

For centuries, the Mercator projection became the de facto standard for world maps, adorning schoolrooms, government offices, and navigation charts. Its familiarity bred a sense of accuracy, yet beneath its practical utility lay a subtle but profound distortion. As Mercator moved away from the equator towards the poles, the projection progressively stretched areas vertically, making landmasses appear larger the farther they were from the equator.

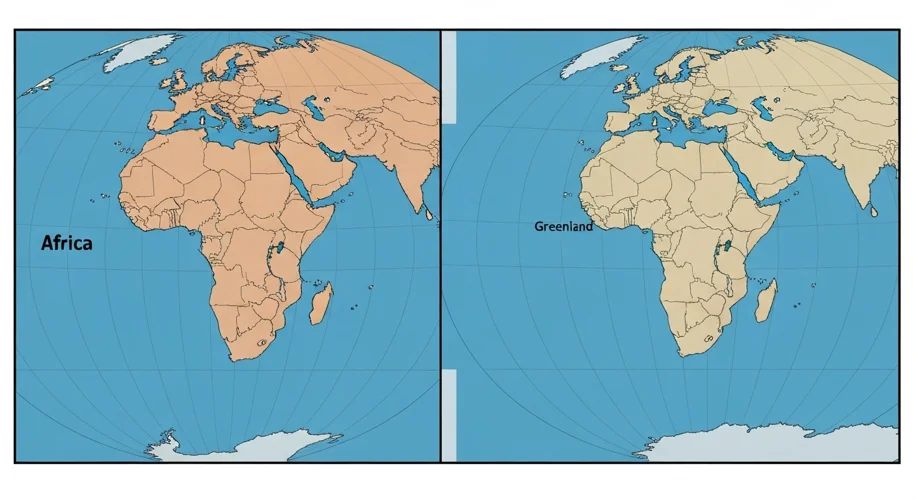

This distortion is most famously, and controversially, applied to the African continent. While Africa is the second-largest continent in the world by land area, roughly 11.7 million square miles, on a Mercator map, it appears disproportionately smaller. In contrast, Greenland, an island nation with less than a quarter of Africa’s landmass, looms large, often depicted as nearly equal in size to Africa itself. Similarly, Russia, Canada, and the United States are dramatically exaggerated, while countries in the Southern Hemisphere, like Brazil and Australia, are significantly shrunk.

This perceived