In the annals of history, few beverages evoke as much immediate sensory recall as beer. We conjure images of frothy tankards, the clinking of glasses, and the refreshing, sometimes malty, taste. But what of the beer of yesteryear, the brews consumed in ages past? Did ‘old beer’ carry a different character, perhaps one tinged with the subtle, lingering essence of smoke?

The notion of a smoky flavor in historical beer might seem unusual to the modern palate, accustomed to meticulously controlled fermentation and filtration. Yet, a deeper dive into the brewing practices of centuries gone by reveals that smoke was not merely an incidental byproduct but often an intrinsic element of the brewing process, leaving its mark on the final product.

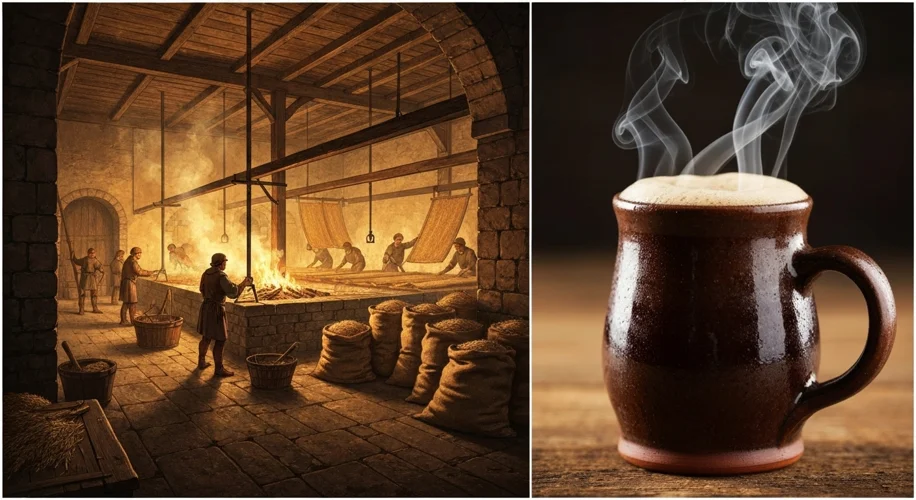

The journey to understanding this smoky nuance begins with the malting process. Before hops became the ubiquitous bittering agent we know today, malted barley was the soul of beer. To create malt, barley grains are germinated and then dried. In the absence of modern kilns, this drying process relied heavily on heat, often generated by open fires. Imagine a medieval brewhouse, the air thick with the aroma of woodsmoke and roasting grains. The barley would be spread out on floors, often over smoldering peat, wood, or even charcoal. The intensity and duration of this exposure directly influenced the malt’s color and flavor. Darker malts, essential for robust, flavorful ales, were subjected to longer drying times closer to the heat source, inevitably absorbing smoky phenols.

The ingredients themselves also played a role. Water quality varied greatly depending on the region, and some water sources, particularly those near peat bogs or marshlands, could impart subtle earthy or even smoky undertones to the beer even before the brewing began. Furthermore, the use of adjuncts like oats or rye, sometimes dried over similar smoky fires, could further contribute to a complex flavor profile.

Fermentation, too, held its own mysteries. While the primary drivers of fermentation were yeast strains, the ambient temperature of the brewing environment, often uncontrolled and influenced by the same fires used for malting, could lead to different yeast behaviors and the production of a wider range of esters and phenols – compounds that contribute to a beer’s aroma and taste. Some historical accounts even suggest that certain brewing vessels or storage containers might have been smoked to preserve them or impart a desired character.

Consider the context of transportation and storage. Before refrigeration and sophisticated bottling, beer was often stored in wooden casks. These casks, frequently charred on the inside to help preserve the wood and prevent leaks, could subtly impart smoky, tannic notes to the beer over time. The longer a beer aged in such a cask, the more pronounced these flavors might become.

While specific recipes and brewing logs from distant centuries are scarce, historical brewing manuals and anecdotal evidence from contemporary writings offer clues. For instance, descriptions of beers from Northern Europe, where wood and peat were abundant fuel sources, frequently allude to a robust, dark, and sometimes ‘pungent’ character, which could easily encompass a smoky element. Beers like Gruit ales, which used a blend of herbs and spices instead of hops for flavoring and preservation, often had a stronger, more assertive flavor profile that could stand up to or complement a smoky malt.

In essence, the ‘old beer’ of historical accounts was a product of its environment and the technology available. The deliberate or incidental use of smoke during malting, the character of the water, the ambient fermentation temperatures, and the storage methods all contributed to a sensory experience far removed from the clean, crisp lagers or balanced IPAs of today. While not every historical beer was necessarily overtly smoky, the potential for that flavor to be present, often as a complex undertone rather than a dominant note, is undeniable. It’s a reminder that the history of beer is not just a story of ingredients and processes, but also of the very air, fire, and earth that shaped its creation.

So, the next time you raise a glass of your favorite brew, spare a thought for those ancient brewers. Their creations, imbued with the very essence of fire and smoke, offered a taste of a world where flavor was as much a consequence of necessity as it was of intention. The smoldering truth is that the history of beer is a rich, complex, and sometimes smoky one.