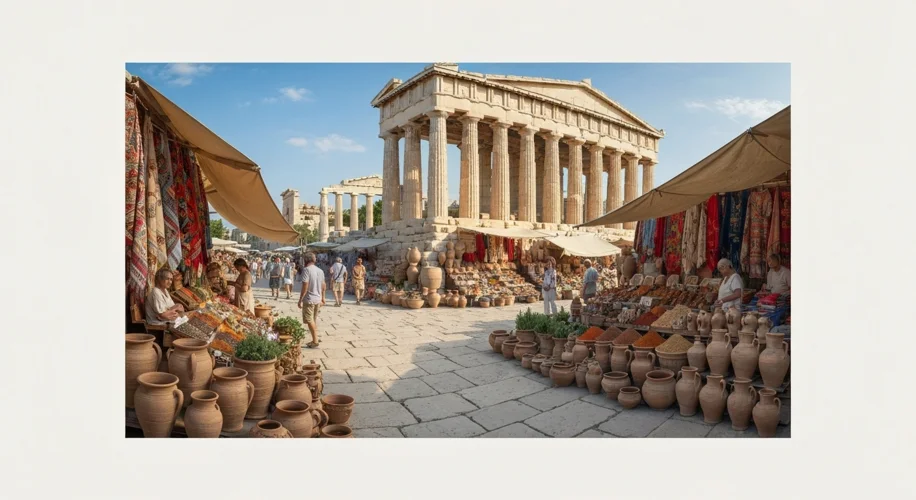

The story of Greece’s economy is a saga woven with threads of ancient brilliance, modern challenges, and an unyielding spirit. For millennia, the Hellenic peninsula has been a crucible of trade, culture, and, inevitably, economic policy. From the bustling agora of Athens to the modern halls of Brussels, the decisions made about taxation, debt, and reform have echoed across centuries, shaping not just the lives of Greeks but the broader currents of global finance.

In the ancient world, Greek city-states like Athens and Sparta developed distinct economic models. Athens, a maritime power, thrived on trade, silver mines, and a sophisticated system of taxation and public finance. The Athenian treasury was funded through taxes on imports and exports, taxes on metics (resident foreigners), and, crucially, the proceeds from its silver mines at Laurion. The state also relied on liturgies, a form of taxation where wealthy citizens funded public services like equipping warships or sponsoring dramatic festivals. This system, while effective in its time, was also susceptible to the vagaries of war and political instability.

The Hellenistic period, following Alexander the Great’s conquests, saw the rise of larger kingdoms and more complex economic interactions. Hellenistic rulers often controlled vast agricultural lands and monopolies on certain goods, using these revenues to fund their armies and administration. Royal treasuries were centralized, and economic policies were geared towards maximizing state income to maintain military superiority and royal prestige.

Fast forward to the modern era, and Greece’s economic journey is a complex tapestry of national aspiration, foreign influence, and existential challenges. After gaining independence from the Ottoman Empire in the early 19th century, Greece embarked on a path of nation-building, often financed by external loans. This early reliance on foreign debt set a precedent that would haunt the country for generations.

The 20th century brought periods of both progress and turmoil. World War I and the subsequent Greco-Turkish War devastated the economy. The interwar period saw attempts at stabilization, but World War II and the brutal civil war that followed plunged Greece into deeper poverty and economic dislocation. Reconstruction efforts in the post-war era, aided by international support, led to significant growth, but underlying structural issues, including a complex and often inefficient tax system and a tendency towards high public spending, persisted.

The late 20th and early 21st centuries saw Greece join the European Economic Community (later the European Union) and adopt the Euro. While accession brought opportunities for investment and integration, it also masked growing fiscal imbalances. Greece’s entry into the Eurozone was facilitated by creative accounting practices, which led to an underestimation of the country’s true debt and deficit levels.

When the global financial crisis hit in 2008, the vulnerabilities in Greece’s economy were brutally exposed. The revelation of its true fiscal situation triggered a sovereign debt crisis that threatened not only Greece but the stability of the entire Eurozone. The subsequent years were marked by a series of severe austerity measures imposed by international lenders (the International Monetary Fund, the European Central Bank, and the European Commission – the “Troika”), coupled with painful fiscal reforms. These reforms included deep cuts to public spending, wage and pension reductions, and significant tax increases.

The impact of these policies was profound. While they aimed to restore fiscal discipline and market confidence, they also led to a deep recession, soaring unemployment (especially among the youth), and widespread social hardship. Greece experienced a significant decline in its Gross Domestic Product, a contraction of its industrial base, and a severe strain on its social welfare systems. Trust in political institutions and international partners eroded.

Analysis of Greece’s economic policy reveals a recurring theme: the challenge of balancing immediate needs with long-term fiscal sustainability. Taxation systems have often struggled with issues of evasion and complexity. Debt management has frequently been reactive rather than proactive. Fiscal reforms, while necessary, have often been implemented in crisis mode, exacerbating their social and economic impact.

The Greek experience offers a stark case study in the complexities of sovereign debt, fiscal policy, and the social contract. It highlights the delicate interplay between national sovereignty, international financial markets, and the well-being of citizens. The lessons learned from Greece’s economic journey continue to inform debates about fiscal responsibility, the structure of monetary unions, and the equitable distribution of economic burdens in an increasingly interconnected world.