In the quiet hum of laboratories, amidst the clatter of machinery and the scent of ozone, a revolution was brewing. It wasn’t a revolution fought with cannons and cavalry, but with whispers of electrons and the meticulous manipulation of matter. The year was 1947, and within the hallowed halls of Bell Laboratories, a device was born that would irrevocably alter the course of human history: the transistor.

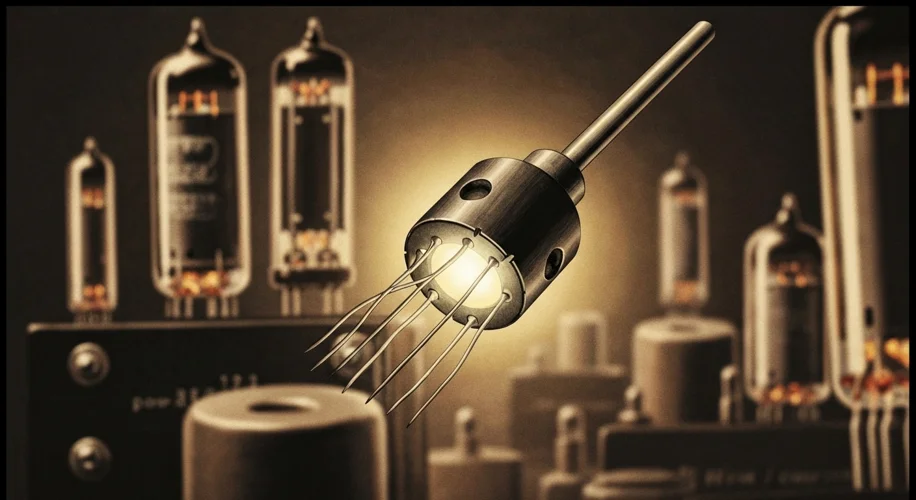

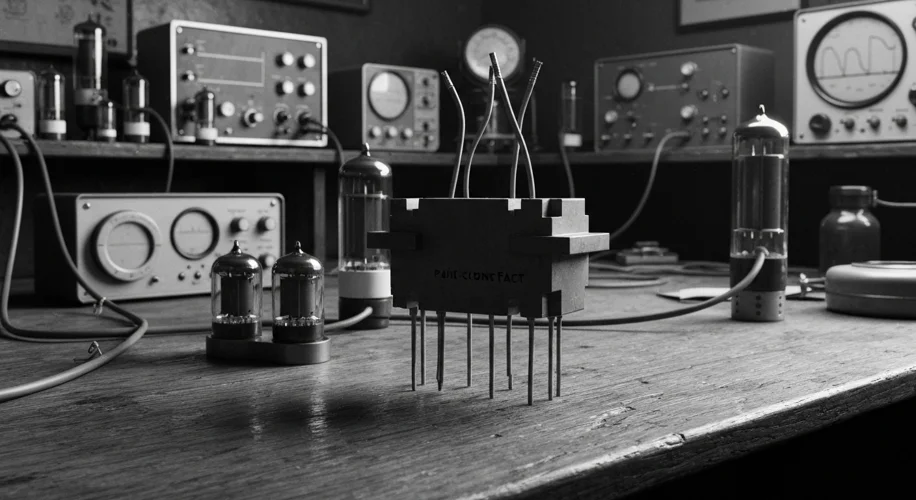

Before the transistor, electronics were beholden to the vacuum tube. These glass bulbs, fragile and power-hungry, were the workhorses of early radio, television, and rudimentary computers. Imagine a world where your radio, if you were lucky enough to own one, was the size of a small suitcase, and where the “personal” computer was a room-sized behemoth that required its own dedicated power plant. This was the reality before the humble transistor.

The story of the transistor’s invention is a tale of collaboration, intellectual curiosity, and a touch of serendipity. At Bell Labs, a team of brilliant minds – John Bardeen, Walter Brattain, and William Shockley – were tasked with finding a solid-state replacement for the vacuum tube. Their quest was driven by the need for more reliable and efficient electronic components, particularly for the burgeoning telecommunications industry.

John Bardeen, a quiet theoretical physicist, brought a deep understanding of quantum mechanics. Walter Brattain, an experimental physicist with a knack for hands-on problem-solving, was the master of the lab bench. William Shockley, the ambitious leader of the group, was a visionary with a keen eye for application.

Their initial experiments focused on understanding the electrical properties of semiconductors, materials like germanium that could conduct electricity under certain conditions. They tried to use a thin semiconductor to amplify an electrical signal, but their early attempts were fraught with difficulties. The presence of impurities and the instability of the material often led to unpredictable results.

One fateful day, in December 1947, Brattain and Bardeen were working with a point-contact transistor. This early iteration involved two closely spaced gold foil contacts pressed against a small piece of germanium. The magic happened when they applied a small voltage to one contact, and a magnified version of that signal emerged from the other. They had achieved amplification, the fundamental building block of electronic devices, without the need for a vacuum.

Shockley, though not directly involved in the crucial December experiments, was the driving force behind the project. He later conceived of the more robust