History is often painted with broad strokes of grand battles, soaring speeches, and sweeping reforms. Yet, beneath the surface of these monumental events lies a subtler, more pervasive force: the quiet art of “malicious compliance.” This isn’t about outright rebellion, but a calculated adherence to rules, orders, or instructions in a way that is technically correct but intentionally disruptive, unhelpful, or even counterproductive.

Is this a modern phenomenon, born of bureaucratic frustrations and digital age disconnects? Or is it a timeless human response to authority, a whisper of dissent in the face of overwhelming command?

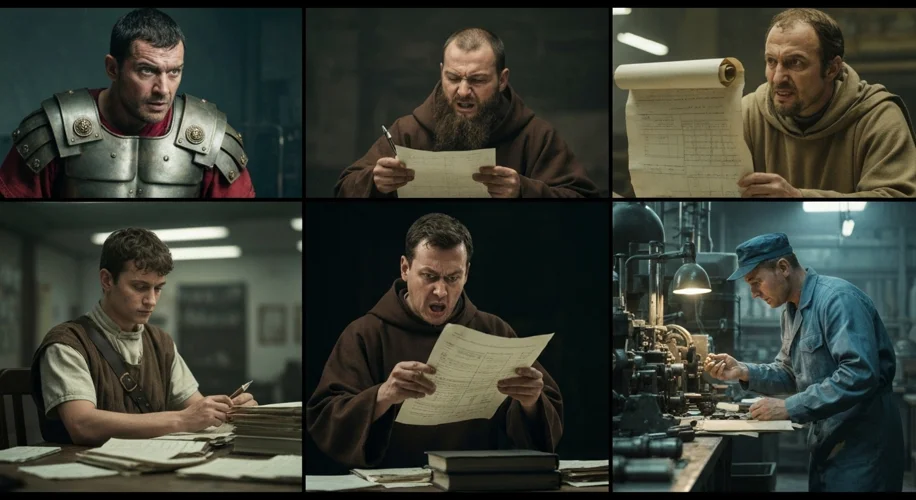

Consider the Roman Republic, a society steeped in tradition and rigid hierarchy. While overt defiance could lead to severe punishment, a legionary or a scribe might find subtle ways to fulfill orders that went against the spirit of the command. Imagine a centurion ordered to build a road with maximum efficiency. He might meticulously follow every outdated regulation regarding material sourcing and labor allocation, ensuring the road was built exactly as per the old law, but at a pace that would make any modern project manager weep. The order was followed, but the intended speed and resourcefulness were lost in the labyrinth of compliance.

Fast forward to the medieval period. In the monasteries, centers of learning and spiritual devotion, monks were bound by strict rules of silence and obedience. A particularly zealous abbot might decree that all labor be performed with utter silence. A monk tasked with copying illuminated manuscripts, a task requiring focus and often vocalization of prayers or chants for rhythm, might suddenly find himself unable to produce his best work. He would meticulously avoid any sound, his pen scratching louder than usual on the vellum, his breathing audible in the oppressive quiet. The command for silence was obeyed, but the artistic quality of the work, and perhaps even the monk’s spiritual connection to it, would suffer.

The Renaissance and the Enlightenment brought new intellectual currents, but also new forms of governance and administration. When Queen Elizabeth I of England needed to manage her growing navy, she relied on a complex system of admirals, captains, and shipwrights. Orders would be issued, often vaguely or with conflicting priorities. A shipwright, tasked with repairing a vessel for a specific mission, might be ordered to use only ‘approved’ materials. If the approved materials were of inferior quality or unavailable, he would procure them with excruciating slowness, citing the Queen’s own regulations. The ship would be ‘ready,’ but its seaworthiness might be compromised, all in the name of following protocol.

Throughout history, figures have used malicious compliance to navigate oppressive regimes or simply to express dissatisfaction without risking outright reprisal. During the American Revolution, the British Crown issued various acts and taxes designed to assert control over the colonies. Colonists, while chafing under these impositions, were often forced to comply. Smugglers might meticulously declare every taxable item, filling out endless forms and declaring even the smallest quantity of undeclared goods, thus slowing down port operations and making legal trade prohibitively cumbersome. This wasn’t about evading taxes entirely, but about making the system so burdensome that it became unsustainable.

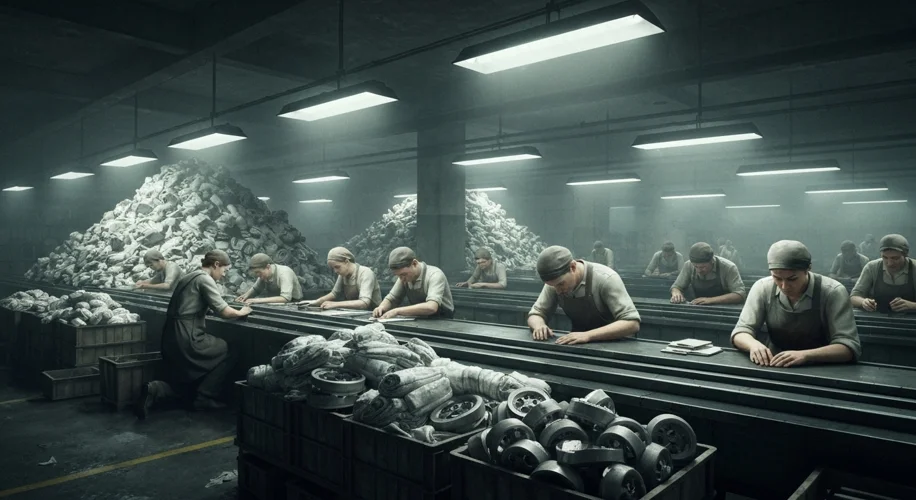

Even in more recent times, the practice persists. During the Cold War, the sheer bureaucracy of the Soviet Union provided fertile ground for malicious compliance. A factory manager, ordered to increase production of a certain good, might meet the quota by producing an overwhelming volume of low-quality, unusable items. The numbers on paper would look impressive, satisfying the higher-ups, but the practical outcome would be waste and inefficiency. This served as a quiet protest against unrealistic demands and a way to subvert the system from within.

What drives this behavior? It can stem from a deep-seated resentment, a feeling of powerlessness, or a desire to reclaim some measure of control in an unyielding system. It’s a way for individuals to assert their agency, to say, “You may control my actions, but you won’t control my intent, nor will I be a willing participant in your flawed designs.” It’s a testament to human ingenuity, a dark and winding path through the corridors of power.

Malicious compliance, therefore, is not a modern invention. It is as old as authority itself, a persistent echo in the human story, demonstrating that while obedience can be compelled, genuine cooperation and spirit cannot always be mandated. It’s the quiet rebellion of the everyday person, a reminder that even within the strictest rules, there is always room for a little bit of mischief, a little bit of passive-aggressive artistry.