The clatter of looms, the hiss of steam, the incandescent glow of new inventions – these were the sounds and sights that heralded a seismic shift in human history. The Industrial Revolution, a period spanning roughly from the late 18th to the mid-19th century, wasn’t just about new machines; it was a profound societal and economic metamorphosis, driven by an unprecedented wave of technological innovation.

Before this transformative era, life for most people was tethered to the rhythm of agriculture. Production was largely artisanal, carried out in homes or small workshops. The pace of life was dictated by the seasons, and social structures were relatively static. Yet, simmering beneath this seemingly placid surface was a growing intellectual curiosity and a burgeoning spirit of inquiry, hallmarks of the Enlightenment, which laid the groundwork for the radical changes to come.

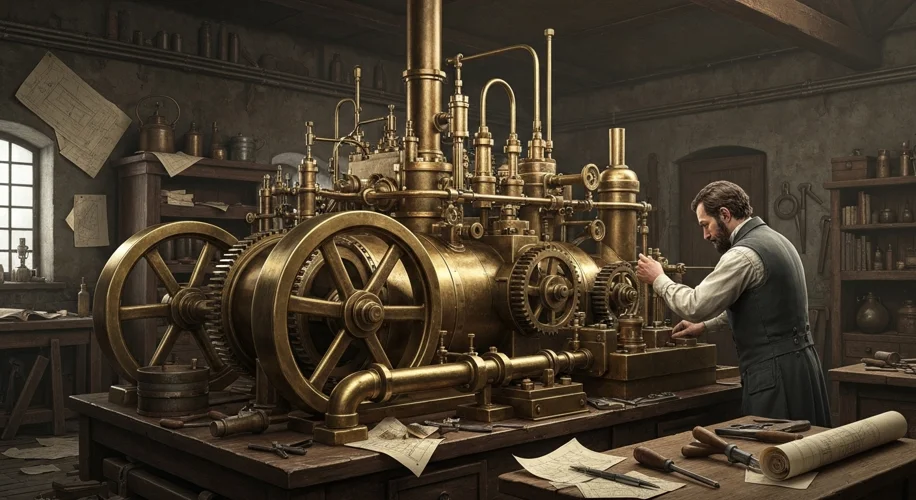

The spark that ignited the revolution can be traced to Great Britain. Factors like abundant natural resources (coal and iron ore), a stable political climate, a growing population that provided both labor and markets, and a thriving mercantile class with capital to invest, all converged to create fertile ground for innovation. The invention of the steam engine, perfected by James Watt in the 1760s and 1770s, stands as a towering achievement of this period. It was a portable, reliable power source that could operate anywhere, liberating factories from the necessity of being located near water sources.

The impact of the steam engine was revolutionary. It powered new machinery in textile mills, like the spinning jenny and the power loom, dramatically increasing the speed and scale of cloth production. This led to the factory system, a new way of organizing labor where workers gathered under one roof to operate machines. Suddenly, goods that were once laboriously crafted by hand could be mass-produced, making them more affordable and accessible.

Beyond textiles, innovation rippled through other sectors. Iron production saw significant advancements, enabling the construction of stronger machines, bridges, and eventually, railways. The development of steam-powered locomotives and ships, like George Stephenson’s “Locomotion No. 1” in 1825, shrunk distances, facilitated trade, and allowed for the unprecedented movement of people and goods.

The social fabric was irrevocably altered. Urbanization accelerated as people flocked from rural areas to burgeoning industrial cities in search of work. This rapid growth, however, often outpaced the development of infrastructure, leading to overcrowded housing, poor sanitation, and the spread of disease. The lives of ordinary workers changed too; they traded the autonomy of agricultural or artisanal labor for the regimented discipline of factory work, often enduring long hours, dangerous conditions, and low wages.

Key figures like Richard Arkwright, often called the “father of the factory system,” pioneered new methods of water-powered textile production, while Eli Whitney’s invention of the cotton gin in America, though a decade later, vastly increased cotton production, fueling the textile industry in both Britain and the United States.

The consequences of the Industrial Revolution were vast and multifaceted. Economically, it spurred unprecedented growth, created new industries, and led to the rise of capitalism as the dominant economic system. Socially, it reshaped class structures, fostered new urban cultures, and eventually, led to the development of labor movements and social reforms as people grappled with the challenges of industrial life.

Culturally, the era’s emphasis on reason, progress, and mechanical efficiency influenced art, literature, and philosophy. The sheer speed of change also generated anxieties about the loss of traditional ways of life and the dehumanizing effects of factory work, themes explored by writers like Charles Dickens.

The Industrial Revolution was not a singular event but a complex, ongoing process. Its legacy is undeniable, shaping the modern world in ways we often take for granted – from the goods we consume to the jobs we do, and the very cities we inhabit. It demonstrated the transformative power of human ingenuity, but also served as a stark reminder of the social and ethical considerations that must accompany technological progress.