In the annals of communication, few technologies commanded the world’s attention quite like the telegraph. For over a century, it was the titan of instant messaging, a marvel that shrunk distances and connected continents. Yet, as the 20th century drew to a close, its reign was definitively ending. On January 25, 1991, AT&T, a company synonymous with telecommunications, quietly discontinued its domestic telegraph services. This was not a dramatic shutdown; rather, it was the final, almost imperceptible flicker of a once-blazing technological torch.

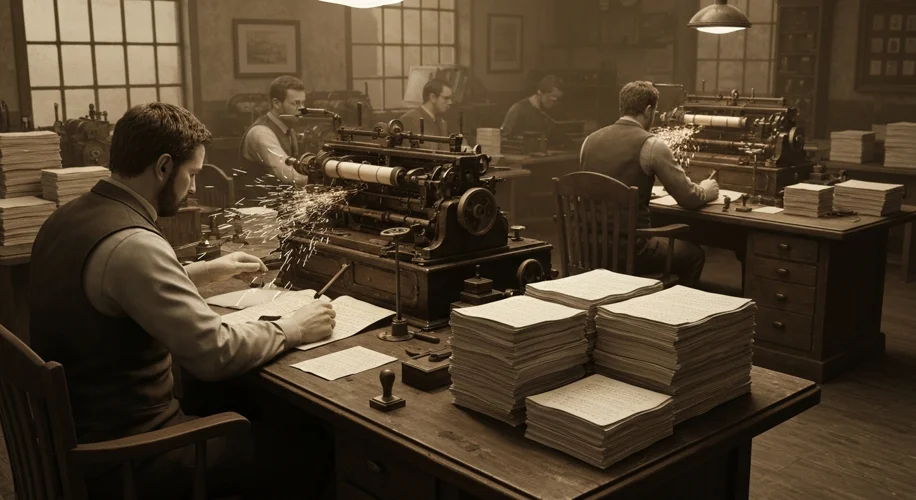

The telegraph, born from the ingenuity of figures like Samuel Morse and Alfred Vail, revolutionized society. Its rhythmic clicks and dits, transmitted over wires, carried news of wars, births, deaths, and fortunes. It was the backbone of business, the conduit for personal connections across vast distances, and a symbol of modernity. The very idea of sending a message faster than a horse could gallop was revolutionary.

By 1991, however, the world had moved on. The telephone, a more immediate and personal form of communication, had long since become commonplace. Fax machines offered a way to transmit documents with unparalleled speed, and the nascent internet, with its email and early online services, was already heralding a new digital age. The telegraph, once the cutting edge, had been steadily relegated to the realm of the quaint and the obsolete.

But who, exactly, was still sending telegrams in 1991? The answer, perhaps surprisingly, isn’t a simple one, and the exact numbers are elusive. AT&T did not maintain specific public figures for its dwindling telegraph user base in the final years. However, historical accounts and industry analyses paint a picture of a service largely supported by niche markets and specific use cases.

One significant user group consisted of individuals sending messages of congratulation or condolence. For a long time, a telegram was the traditional, almost ceremonial, way to mark significant life events or to express sympathy. Even as email and faxes became more prevalent, the gravitas and formality of a telegram retained a certain appeal for these deeply personal, yet publicly acknowledged, milestones. The physical delivery of a telegram, often by a uniformed messenger, lent it a weight that an electronic notification struggled to replicate.

Businesses, too, continued to utilize the service, though their reliance had diminished. For urgent, critical notifications where the perceived reliability of the telegraph was still valued, or in areas where other communication infrastructure was less robust, it maintained a foothold. Think of certain types of financial alerts or legal notices where a verified, albeit slower, transmission was preferred over the ephemeral nature of a phone call or a potentially intercepted email.

Then there were the enthusiasts and collectors – those who appreciated the history and mechanics of the telegraph itself. For them, sending a telegram was an act of connection to the past, a way to experience a piece of technological history firsthand. These were the hobbyists who understood the language of Morse code, the individuals who might still possess a working telegraph key in their own homes.

It’s important to understand that AT&T’s decision wasn’t necessarily driven by a massive, active subscriber base, but rather by the economics of maintaining an aging infrastructure. The cost of keeping the telegraph network operational, with its dedicated lines, specialized equipment, and personnel, likely outweighed the revenue generated by its shrinking user base. The service was a relic, and the company was streamlining its operations to focus on the future.

The discontinuation of AT&T’s telegraph service in 1991 marked a symbolic end to an era. While the exact number of users remains a matter of historical estimation rather than precise data, it’s clear that by this point, the telegraph had transitioned from a mass communication tool to a specialized, legacy service. Its users were a dedicated few, clinging to its unique blend of formality, tradition, and historical resonance in a world rapidly accelerating towards digital interconnectedness. The silence that followed the final click of the telegraph key was not just the end of a service, but a poignant reminder of how swiftly technology marches forward, leaving even its most revolutionary ancestors in its wake.

The telegraph’s story is a powerful lesson in technological evolution. It demonstrates how innovations that once seemed indispensable can, in the blink of an eye from a historical perspective, become charming relics. Its discontinuation in 1991 wasn’t a death knell, but a quiet fade-out, the last vestiges of a technology that had, for so long, carried the world’s most important messages.