In the spring of 1961, a courtroom in Jerusalem became the stage for a drama that gripped the world, a trial that sought to bring one of history’s most reviled figures to justice. Adolf Eichmann, the SS-Obersturmbannführer who orchestrated the logistical backbone of the Holocaust, stood in the dock, his fate hanging in the balance. This was not merely a legal proceeding; it was a profound reckoning with the unimaginable horrors of the Nazi regime, a testament to the resilience of memory, and a stark reminder of humanity’s capacity for both profound evil and unwavering justice.

The Shadow of the Final Solution

To understand the gravity of the Eichmann trial, one must first grasp the infernal machinery he helped to build. Eichmann was not a frontline soldier or a charismatic ideologue; his role was far more insidious. He was a bureaucrat, a meticulous planner, a man whose efficiency was dedicated to the systematic extermination of an entire people. As head of the Gestapo’s Jewish Affairs Office, he organized the deportation of millions of Jews from across Europe to ghettos and, ultimately, to death camps like Auschwitz-Birkenau. His responsibility was the trains, the schedules, the loading of cattle cars, the cold, hard logistics of genocide.

He operated within the suffocating culture of the SS, an organization that prided itself on discipline, obedience, and a fanatical adherence to Nazi ideology. Eichmann embraced this culture, seeing his work not as murder, but as a duty, a necessary task to fulfill the regime’s vision. He famously stated after the war, “I was merely a cog in the machinery.” This statement, uttered in various forms, would become a central theme – and a point of fierce contention – during his trial.

The Hunt for the Architect

For years after the war, Eichmann vanished, a ghost in the collapsing Reich. He found refuge in Argentina, living under a false identity, a seemingly ordinary man carrying an extraordinary burden of guilt. However, the memory of the Holocaust, and the burning desire for justice, did not fade. In the late 1950s, aided by Nazi hunters and intelligence services, Eichmann was located. The story of his capture in May 1960 is itself the stuff of legend: a covert operation by Israel’s intelligence agency, Mossad, a daring snatch-and-grab on foreign soil, and his subsequent transport to Jerusalem to face trial.

His captors were driven by a powerful imperative: to ensure that such a crime would never be forgotten, and that its perpetrators would be held accountable. Israel, a nation forged in the ashes of the Holocaust, felt a profound obligation to bring Eichmann to trial. The trial was not just about Eichmann; it was about vindicating the victims, about bearing witness to the truth, and about affirming the universal principles of justice.

The Trial of the Century

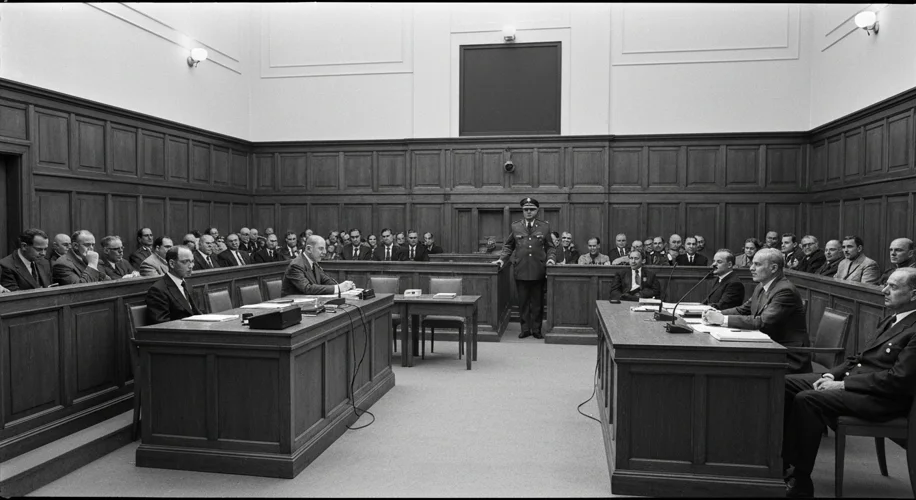

The trial commenced on April 11, 1961, presided over by three Israeli judges. The prosecution, led by Attorney General Gideon Hausner, presented an overwhelming case, not just against Eichmann as an individual, but against the entire Nazi apparatus of destruction. Instead of relying solely on historical documents, the prosecution called over 100 Holocaust survivors to the stand. Their testimonies, raw and heartbreaking, painted a vivid, visceral picture of the suffering Eichmann had orchestrated. They spoke of the cattle cars, the selections, the gas chambers, the constant fear, and the systematic dehumanization. These were not abstract historical facts; they were deeply personal accounts of unimaginable horror.

Eichmann, for his part, presented himself as a subordinate following orders, a man caught in the currents of history. He attempted to distance himself from the brutal realities of his actions, focusing on the bureaucratic details of his role. He maintained that he was merely doing his job, that he had no personal hatred for the Jews, and that he was powerless to deviate from his directives. This defense, the classic