The year is 1918. The world is weary, battered by the Great War. Soldiers, already weakened by the trenches and the grim realities of combat, begin to fall ill with a new, terrifying enemy. This wasn’t a foe of steel and gunpowder, but an invisible adversary that moved with chilling speed and stealth: the H1N1 influenza virus, more commonly known as the Spanish Flu.

A Silent Invader Arrives

While the war raged, gripping Europe and beyond in its brutal embrace, a different kind of battle was being waged on a global scale. The Spanish Flu pandemic, which swept across the planet between 1918 and 1919, was unlike anything the world had ever witnessed. It was a swift, merciless killer, leaving an estimated 50 million dead – more than the combined casualties of World War I.

The origins of the pandemic are still debated among historians and scientists, with early outbreaks reported in Kansas, USA, and France. However, the name “Spanish Flu” is a misnomer. Spain, being neutral in World War I, had a free press that reported on the outbreak extensively, leading many to believe it originated there. In reality, wartime censorship in Allied and Central Powers nations likely suppressed early news, giving the false impression that Spain was the epicenter.

The First Wave and the W-Shaped Curve

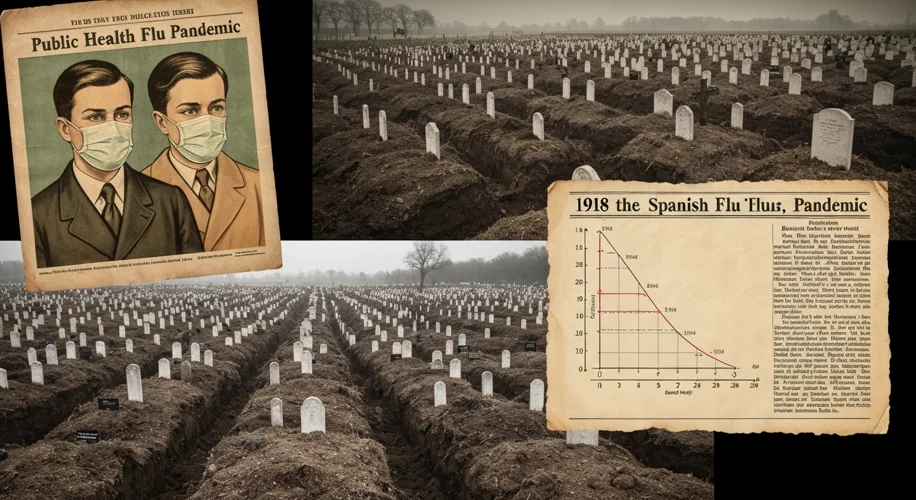

The initial wave of the flu in the spring of 1918 was relatively mild. Many infected individuals recovered. However, as the summer waned and autumn approached, a mutated, far more virulent strain emerged. This second wave was unlike any flu before it, striking down the young and healthy with alarming ferocity. Typically, influenza disproportionately affects the very young and the elderly. The Spanish Flu, however, exhibited a peculiar “W-shaped” mortality curve, with peaks in those age groups but also a significant spike in healthy adults between the ages of 20 and 40.

Imagine the scene: bustling military camps, troop transports packed with soldiers, and crowded city streets. These were fertile grounds for the virus. The close proximity of soldiers, often in poor sanitary conditions, facilitated rapid transmission. When these soldiers returned home, they carried the deadly contagion with them, spreading it across continents and to every corner of the globe.

The Unseen Enemy in Action

The symptoms were horrific and often swift. A sudden onset of fever, aches, and fatigue would quickly give way to a severe cough, sometimes producing bloody sputum. In the most severe cases, the lungs would fill with fluid, leading to suffocation. The disease was so potent that healthy individuals could go from feeling slightly unwell to death within 24 to 48 hours.

Public health measures were often overwhelmed or misunderstood. Quarantines were implemented, public gatherings were discouraged, and the use of masks became widespread in many cities. However, without a clear understanding of germ theory or the availability of antivirals or vaccines, these measures offered limited protection against such a relentless foe. Schools, theaters, and businesses were forced to close. The fabric of daily life was torn asunder by fear and loss.

The Human Toll

The sheer scale of death was staggering. Entire families were wiped out. Communities were devastated. The global death toll is estimated to have been between 20 and 50 million, with some estimates reaching as high as 100 million. This was a higher mortality rate than the Black Death of the 14th century, and it occurred in an era of unprecedented global connectivity.

Consider the case of the United States. In October 1918 alone, an estimated 195,000 Americans died from the flu. The country’s population was roughly one-third of what it is today. The pandemic disproportionately affected indigenous populations in the Americas, with some communities experiencing mortality rates as high as 20-30%.

Legacy and Lessons

The Spanish Flu pandemic left an indelible mark on the 20th century. It underscored the vulnerability of human populations to novel infectious diseases and highlighted the importance of public health infrastructure. The pandemic also had significant social and economic consequences, disrupting labor markets, slowing down industrial production, and contributing to social unrest in some regions.

The experience of 1918-1919 spurred advancements in epidemiology and public health. It led to the establishment of national health organizations and a greater emphasis on disease surveillance. Yet, as history has shown, humanity remains susceptible to the threat of pandemics. The lessons learned from the Spanish Flu – the importance of swift action, clear communication, scientific research, and global cooperation – remain as relevant today as they were over a century ago.

The Spanish Flu was a stark reminder of nature’s power and humanity’s fragility. It was a silent war, fought on a global scale, and its echoes continue to resonate, shaping our understanding of public health and our preparedness for future health crises.