History is not a static monument, carved in stone for all eternity. Instead, it is a living, breathing entity, constantly being re-examined, reinterpreted, and, yes, revised. The very concept of ‘revisionism’ in history often conjures images of deliberate distortion or outright denial, a nefarious attempt to rewrite the past for present-day agendas. But what if revisionism is not inherently a dirty word? What if it is, in fact, the engine of historical understanding, the very process by which we move closer to a more accurate and nuanced grasp of what truly happened?

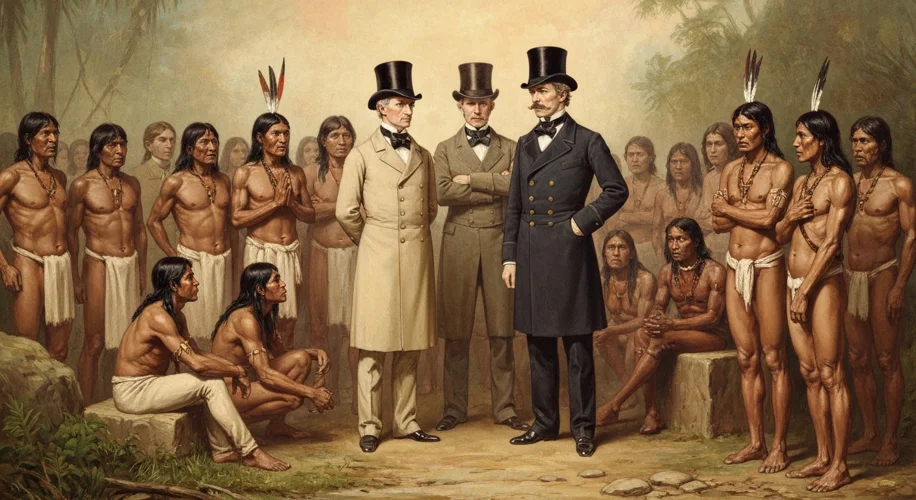

To understand revisionism, we must first acknowledge that historical narratives are rarely singular or simple. They are constructed by individuals, societies, and cultures, each with their own perspectives, biases, and access to information. For centuries, the dominant narratives of many historical events were shaped by the victors, the powerful, or those who controlled the means of dissemination. Think of the colonial histories of vast empires, where the subjugation of indigenous peoples was often framed as a civilizing mission, a benevolent act of bringing progress and enlightenment.

Take, for instance, the traditional understanding of Christopher Columbus. For generations, he was lauded as a brave explorer who “discovered” America, a heroic figure who expanded the known world. This narrative, deeply ingrained in Western education, focused on his voyages and his supposed bravery, largely ignoring the devastating impact his arrival had on the indigenous populations of the Americas. It was through revisionist scholarship – the work of historians who actively sought out neglected sources, listened to marginalized voices, and challenged the prevailing orthodoxy – that a more complex and, frankly, more accurate picture began to emerge. These revisionist accounts brought to light the immense suffering, displacement, and violence inflicted upon Native Americans, fundamentally altering our understanding of Columbus’s legacy from “discoverer” to a figure synonymous with conquest and exploitation.

This process isn’t limited to grand narratives of exploration and conquest. Consider the history of World War II. For decades, the Allied perspective dominated, portraying a clear-cut battle between good and evil. However, revisionist historians, examining newly available archives and employing different theoretical frameworks, have explored the complexities of wartime decision-making, the ethical dilemmas faced by leaders, and the nuanced motivations of various actors. This doesn’t necessarily mean excusing atrocities but rather understanding the multifaceted nature of conflict and the human factors involved.

But here’s where the line between legitimate reinterpretation and malicious distortion becomes crucial. Legitimate historical revisionism is characterized by rigorous research, engagement with primary sources, and a willingness to follow evidence wherever it leads. It doesn’t discard established facts but rather re-examines them, placing them in new contexts or challenging long-held assumptions. It’s an ongoing conversation, a constant refinement of our understanding.

Distortion, on the other hand, often ignores or cherry-picks evidence, manipulates facts to fit a pre-determined conclusion, and is frequently driven by ideology or agenda rather than a genuine pursuit of truth. Holocaust denial is a stark and abhorrent example of historical distortion, where fabricated narratives are used to erase the memory of an atrocity and promote hateful ideologies. Similarly, attempts to downplay the severity of slavery or the brutality of colonial regimes often fall into the category of distortion.

The digital age has amplified both the potential for legitimate revisionism and the peril of distortion. The internet provides unprecedented access to information, allowing for broader collaboration and the sharing of diverse perspectives. Yet, it also serves as a fertile ground for misinformation and the rapid spread of pseudohistorical narratives. The ease with which information can be shared, without the gatekeepers of traditional academic publishing, means that distinguishing between scholarly revisionism and politically motivated falsehoods can be challenging for the average reader.

Ultimately, engaging with history requires an open mind and a critical eye. We must be willing to question established narratives, to embrace new interpretations when they are supported by evidence, and to be wary of those who seek to manipulate the past for their own ends. Revisionism, when practiced with integrity and rigor, is not an enemy of history; it is its most vital ally, ensuring that the echoes of the past continue to speak to us with ever-increasing clarity.