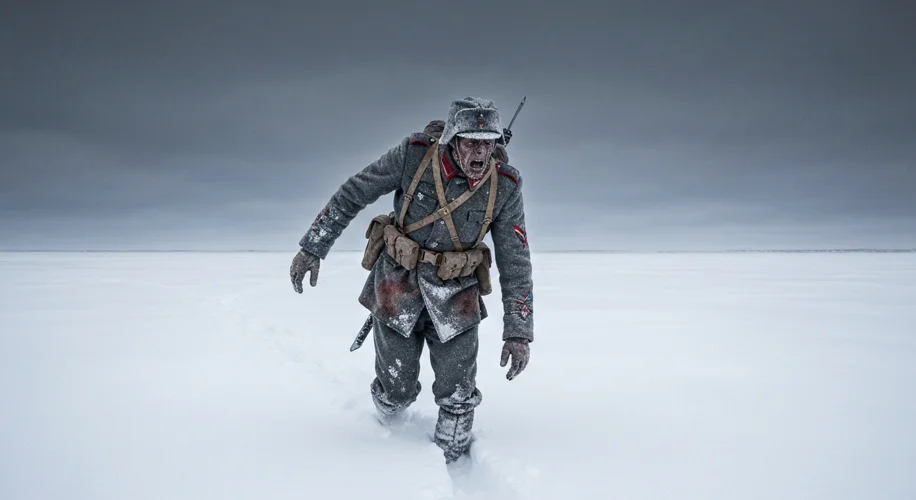

The year is 1812. The Grande Armée, Napoleon Bonaparte’s seemingly invincible force, lay shattered on the frozen plains of Russia. It was not the thunder of cannons or the clash of swords that claimed the most lives, but the brutal, unforgiving hand of winter. For a common soldier, stripped of glory and stripped of hope, the retreat from Moscow was not a strategic maneuver, but a desperate fight for survival against an enemy more formidable than any army: the Russian winter.

Jean-Luc Dubois, a young farmer from Provence, had once marched with pride under Napoleon’s banner. He’d dreamed of glory, of bringing French ideals to the vast eastern lands. Now, his dreams were shattered, replaced by the gnawing ache of hunger and the biting sting of frost. The retreat had begun weeks ago, a chaotic scramble southwards as the Grand Army, ravaged by battles, disease, and scorched-earth tactics, desperately sought to escape the trap they had fallen into.

The initial advance into Russia had been a spectacle of power. Over 600,000 men, a dazzling array of uniforms, banners, and artillery, had marched east. But by November, when the retreat began in earnest, the Grande Armée was a ghost of its former self. Disease had run rampant, starvation was a constant companion, and the Cossacks, the light cavalry of the Russian army, were a relentless menace, harrying the flanks and rear of the retreating columns. The Russians, under General Kutuzov, had wisely avoided a decisive pitched battle, instead employing a strategy of attrition and scorched earth, denying the invaders supplies and forcing them deeper into their own doomed enterprise.

Jean-Luc remembered the early days of the retreat with a shudder. The snow, initially a novelty, became a relentless enemy, burying supplies, freezing muskets, and stealing warmth. Each step was an act of will. The once proud soldiers were now a ragged, desperate mob. Discipline had dissolved, replaced by the primal instinct for survival. Men abandoned their posts, their comrades, even their wounded, driven by the overwhelming urge to escape the relentless cold and the pursuing enemy.

“We were not soldiers anymore,” Jean-Luc recounted years later, his voice raspy with age. “We were ghosts, wandering in a white hell. The cold… it seeps into your bones, steals your thoughts, your very will to live. You see men fall, and you can do nothing but keep moving, or you too will join them.”

The challenges were immense. Food was scarce, often little more than frozen horsemeat or a handful of grain scavenged from abandoned villages. Water had to be melted from snow, a painstaking process that further drained precious energy. Frostbite was a constant threat, turning fingers and toes black and rendering limbs useless. Men who succumbed to the cold or exhaustion were left behind, their bodies quickly claimed by the unforgiving landscape, becoming part of the frozen testament to Napoleon’s hubris.

The retreat was a brutal lesson in the fragility of human life and the sheer power of nature. For every soldier lost to battle, ten perished from hunger, disease, and the biting cold. The legendary resilience of the French soldier was tested to its absolute limit, and for many, it was a test they could not pass.

By the time the remnants of the Grande Armée reached the Niemen River in December, fewer than 100,000 men remained out of the original 600,000. The vast majority had been lost, not to the enemy’s bayonets, but to the relentless, indifferent fury of the Russian winter. Jean-Luc, miraculously, was among the few who made it back, but the scars, both physical and psychological, would remain with him for the rest of his life.

The impact of this catastrophic retreat was profound. It crippled Napoleon’s military might, emboldened his enemies, and shattered the myth of his invincibility. It served as a stark reminder that even the greatest of military geniuses could be undone by the elemental forces of nature and the logistical nightmares of a protracted campaign. For the survivors, like Jean-Luc, the return was not a return to glory, but a return to a life forever marked by the ghost of the Russian winter, a chilling testament to the human cost of imperial ambition.

The retreat from Russia was more than just a military defeat; it was a human tragedy of epic proportions. It stands as a somber monument to the price of hubris, the power of nature, and the enduring struggle for survival against impossible odds.