The 19th century was a kaleidoscope of shifting empires, burgeoning nationalisms, and clashing ideologies. For many European soldiers, it was a time of upheaval and uncertainty. Yet, for a select few, the vast and complex Ottoman Empire offered a surprising haven, a place where they could reinvent themselves, rise through the ranks, and even find a new spiritual home. These weren’t mere mercenaries; they were men who, for a myriad of reasons, chose to defect or convert, leaving behind their old lives to embrace a new one under the Ottoman crescent.

Imagine a young Polish officer, his homeland partitioned and his dreams of freedom shattered. He finds himself in the heart of the Ottoman Empire, not as a conqueror, but as a potential leader. This was the reality for Jozef Bem, a name that would become synonymous with military prowess in both Polish and Ottoman history. Born in Tarnów in 1794, Bem was a veteran of the Polish November Uprising against Russia. When the uprising failed, he found himself a fugitive, his options dwindling. The Ottoman Empire, often at odds with Russia, saw an opportunity. In 1849, Bem, along with other Polish exiles, arrived in Constantinople, offering his considerable military experience to the Sultan.

Bem was not an anomaly. The Ottoman Empire, a multi-ethnic, multi-religious state stretching across three continents, had a long tradition of incorporating foreign talent. For centuries, Janissaries, elite infantry units, were recruited from Christian populations across the empire, converted to Islam, and trained to be fiercely loyal to the Sultan. While the Janissary corps was eventually abolished in the early 19th century, the principle of drawing on external military expertise remained. The empire faced constant threats from internal revolts and external pressures from European powers like Russia, Austria, and Britain. Modernizing its army was a critical imperative, and European officers, especially those with practical battlefield experience, were highly sought after.

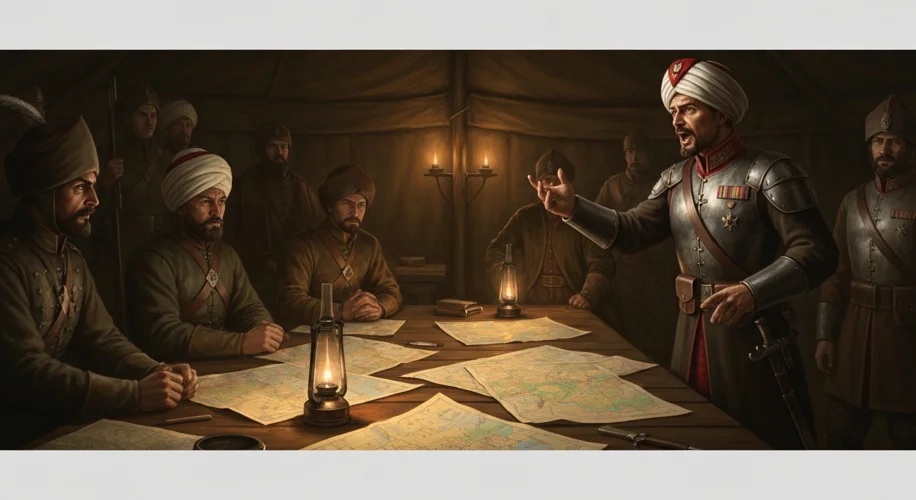

Bem’s conversion to Islam, taking the name Murat Pasha, was not just a personal spiritual journey but a strategic necessity for his integration and advancement. He quickly proved his worth, leading Ottoman forces in the Crimean War and later organizing the defense of Transylvania. His tactical genius and leadership inspired loyalty among the diverse troops he commanded. He was seen by many Ottomans not as a foreigner, but as a valuable asset, a testament to the empire’s capacity to absorb and elevate talent, regardless of its origin.

Another compelling figure is Mustafa Pasza, formerly known as Leopold von Coronini, an Austrian officer who found his fortunes reversed. Details of his early life are scarce, but his defection and subsequent rise within the Ottoman military speak volumes about the opportunities available. He too converted to Islam and rose to significant command, serving with distinction and earning the respect of his Ottoman peers. These men, stripped of their former allegiances by circumstance or choice, found a new identity and a path to power within the Ottoman hierarchy.

The perception of these converts and defectors within Ottoman society was complex. While officially lauded for their skills and loyalty, there were undoubtedly underlying currents of suspicion or perhaps amusement. To the traditional Ottoman elite, these men were outsiders who had adopted their faith and customs, a unique phenomenon. Yet, their military successes and their integration into the Ottoman military structure often trumped any initial reservations. They were proof that merit, rather than solely birthright, could lead to high office.

These individuals were not just soldiers; they became powerful symbols. For the Ottoman Empire, they represented a successful assimilation of foreign expertise, a sign of its enduring strength and adaptability in a rapidly changing world. For the European powers, they were often viewed with a mixture of bewilderment and condemnation – as traitors, renegades, or simply opportunistic adventurers. Yet, their stories paint a nuanced picture of the 19th-century geopolitical landscape, where loyalties were tested, and the lines between enemy and ally, between old life and new, could become remarkably blurred.

Their legacy is a testament to the complex tapestry of the Ottoman Empire and the individuals who, by choice or by fate, wove themselves into its fabric. They were eagles that, having flown far from their native nests, found a new sky under the crescent, leaving an indelible mark on military history and the grand narrative of Ottoman power. Their lives serve as potent reminders that history is not just about grand battles and political maneuvers, but about the profound personal journeys of individuals navigating the currents of change, seeking new homes and new destinies.