The year is 410 AD. The Roman legions, the very backbone of Britannia, are being recalled to defend the heart of the Empire. A vacuum is left, a void that will soon be filled by waves of Germanic peoples – Angles, Saxons, and Jutes. For centuries, these newcomers have been painted with a broad brush as the sole architects of what we now call Anglo-Saxon England. Their arrival is often depicted as a dramatic invasion, a swift replacement of the Romano-British population. But what if the story is far more complex, a vibrant tapestry woven from threads originating far beyond the shores of northern Europe?

Recent breakthroughs in ancient DNA analysis are beginning to rewrite this narrative, revealing a surprisingly diverse genetic landscape within early medieval England. Forget the monolithic image of a purely Germanic influx; the truth is far richer and more interconnected.

Imagine a young man named Cynric, born in the 5th century in what is now Wessex. His ancestors, we might assume, arrived on longships from Germania. But imagine Cynric’s surprise, and perhaps his ancestors’ if they could return, to learn that his DNA tells a different story. Studies published in journals like Nature and Cell have analyzed skeletal remains from Anglo-Saxon cemeteries, comparing their genetic makeup to modern populations and to ancient samples from continental Europe and beyond. What they’ve found is that while a significant portion of the ancestry does indeed trace back to Germanic regions, there are also surprising connections to other parts of Europe, and even hints of something more.

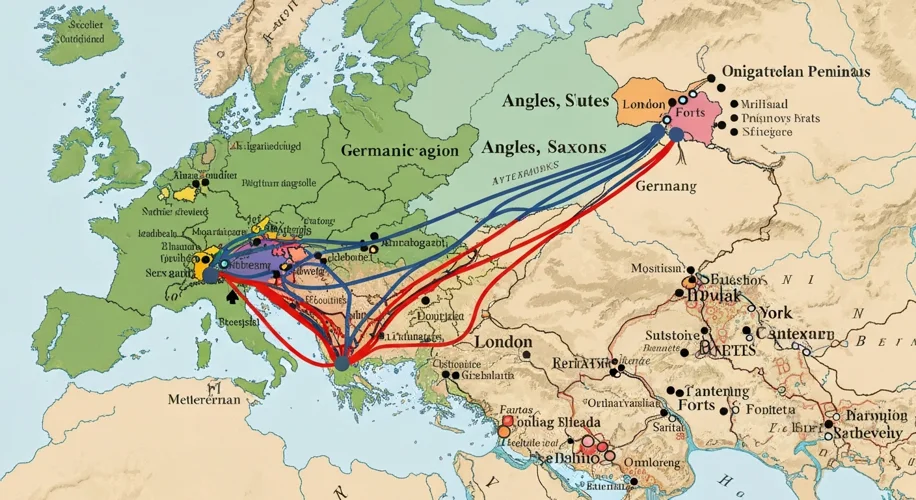

Consider the migration patterns of the period. It wasn’t a single, organized fleet sailing with a singular purpose. It was a complex, multi-generational movement. People moved for a multitude of reasons: for land, for trade, for safety, or perhaps fleeing conflict themselves. Some may have been mercenaries, former soldiers of the Roman army who settled in Britain after their service. Others might have been part of established trade networks that existed long before the Roman withdrawal. The genetic data suggests that individuals with ancestry from areas like the Rhineland, Frisia, and even Denmark were indeed prominent. But there’s more.

Dr. H. A. Kelly, in his extensive work on Anglo-Saxon settlement, highlights the fluid nature of these early medieval societies. Boundaries were porous, and identity was not as rigidly defined as we might assume. The genetic studies corroborate this, indicating that while the Germanic component is strong, there are also clear genetic links to the pre-existing Romano-British population. This wasn’t a simple case of one group annihilating another; it was a process of assimilation, intermingling, and cohabitation.

Furthermore, the genetic data hints at even wider connections. Some studies have identified genetic markers that suggest ancestry from regions further south in Europe, possibly from areas that were once part of the Roman Empire’s vast reach. This raises fascinating questions: were these individuals who migrated later, perhaps during the height of Anglo-Saxon settlement, or were they part of a more complex, earlier interaction?

Imagine a bustling port town on the Kentish coast, circa 600 AD. Merchants from across the known world would have traded goods – pottery, textiles, perhaps even exotic spices. It’s not inconceivable that some of these traders, or their families, decided to stay, integrating into the growing Anglo-Saxon communities. Their genetic legacy, however small, would have become a part of the ever-evolving tapestry of England.

This new understanding of Anglo-Saxon origins has profound implications. It challenges the simplistic narratives of invasion and conquest, pushing us to see these early medieval centuries as a period of dynamic interaction and cultural fusion. It underscores that migration is not a new phenomenon, and that even in the distant past, human populations were far more interconnected than we often imagine.

The implications for our understanding of cultural exchange are immense. It wasn’t just about new languages and new customs arriving; it was about the blending of peoples, the creation of new identities from a mosaic of inherited traditions. The very foundations of English culture, language, and identity were laid by a more diverse group of people than previously acknowledged.

So, the next time you think of the Anglo-Saxons, picture not just the fierce warriors from the north, but a broader spectrum of peoples. Imagine Cynric, a young man of Wessex, whose DNA whispers tales of journeys from many lands, a testament to the enduring human drive to explore, to settle, and to forge a future in new horizons. The story of Anglo-Saxon England is not a tale of isolated beginnings, but a chapter in the grand, ongoing narrative of human migration and connection.