Imagine a world centuries before the internet, before jet planes, a world where the journey of a single object or idea across continents was an epic undertaking, fraught with peril and wonder. This was the reality of the 7th century, a period often shrouded in the ‘Dark Ages’ myth, yet one teeming with vibrant networks of trade and cultural exchange that connected distant corners of the globe. And the most startling evidence of this interconnectedness? The discovery of West African DNA in England.

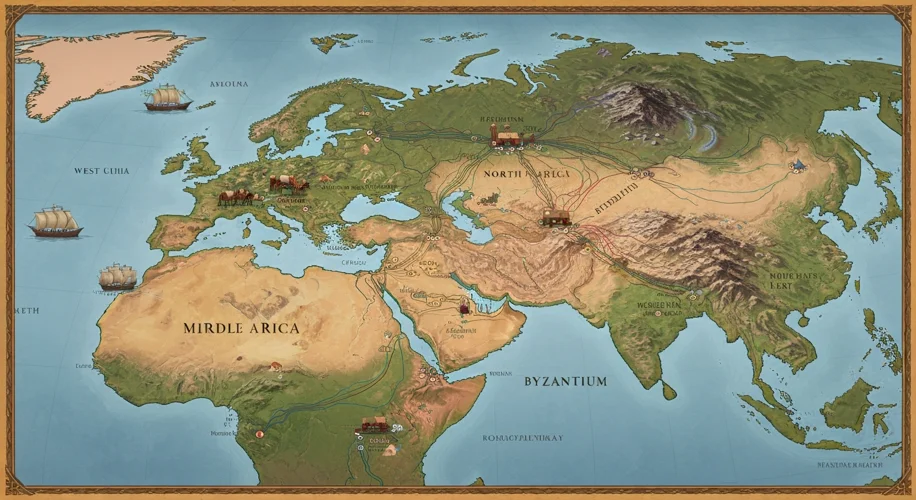

For too long, our understanding of the early medieval period has been colored by a Eurocentric narrative, focusing on isolated kingdoms and nascent empires. But the truth is far more complex and interconnected. The 7th century, particularly, was a time of profound change. The Roman Empire had fractured, the Byzantine Empire was asserting its influence in the East, and the rise of Islam was about to reshape the political and cultural landscape of the Mediterranean and beyond. Amidst this flux, trade routes, some ancient and some newly forged, continued to pulse with activity.

Consider the vast reach of the Byzantine Empire. Its influence, and the goods that flowed through its territories, extended far beyond its immediate borders. Byzantine coins, for example, have been found in archaeological sites from Scandinavia to Central Asia. These weren’t just currency; they were tangible proof of a desire for goods and a recognition of a shared economic sphere. Silks from the East, spices from India, amber from the Baltic, and slaves from various regions were all part of this intricate web.

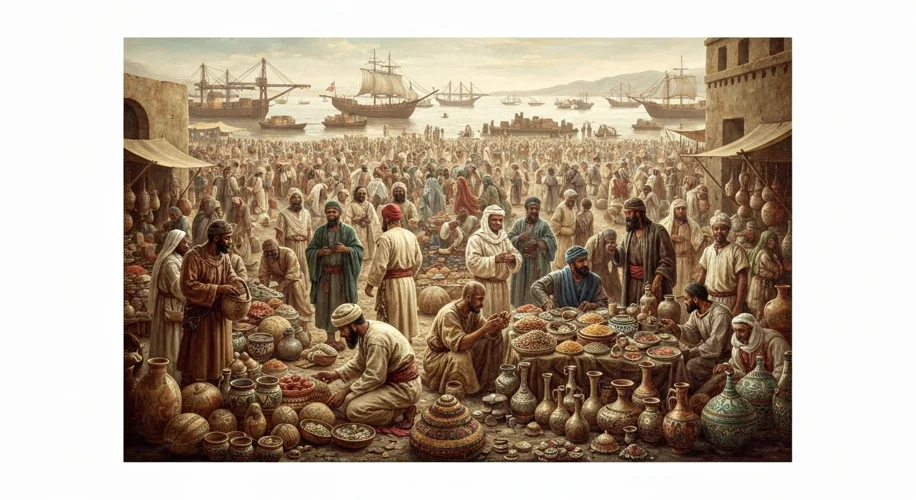

But perhaps the most dynamic force in the 7th century was the burgeoning trade network that emerged from the Arabian Peninsula. The Islamic conquests, while often viewed through a military lens, were also inextricably linked to trade. The new caliphates, stretching from Spain to Persia, facilitated and protected trade routes, making it safer and more efficient to move goods across vast distances. Merchants, driven by profit and curiosity, traversed deserts, navigated seas, and crossed mountain ranges, carrying not just wares but also stories, languages, and beliefs.

This exchange wasn’t limited to tangible commodities. Ideas, technologies, and religious beliefs traveled alongside the caravans and ships. Buddhism, for instance, had already spread from India across Central Asia centuries before, and in the 7th century, its influence continued to deepen. Christianity, already established in the Byzantine Empire and parts of Europe, also spread through trade and missionary efforts. And, of course, the new faith of Islam rapidly expanded its reach, carried by merchants, scholars, and conquerors.

It is within this context of a globally connected 7th century that the discovery of West African DNA in England becomes so profound. For decades, archaeologists and historians have debated the extent of African presence in early medieval England. While evidence of trade with North Africa existed, the genetic findings suggest a deeper, more personal connection. This isn’t just about the movement of goods; it’s about the movement of people, their lives, their families, and their descendants.

Imagine a West African individual, perhaps a merchant, an enslaved person, or even a diplomat, undertaking the arduous journey north. They would have traversed Saharan trade routes, likely passed through North Africa, and then journeyed across the Mediterranean and up through Europe. Their presence in England, evidenced by their DNA centuries later, speaks volumes about the resilience of human networks and the profound, often overlooked, diversity of early medieval societies.

This discovery challenges the simplistic narrative of isolated, homogenous cultures. It compels us to reconsider who was