In the quiet corners of memory, a shadow began to lengthen in the early 20th century, a shadow that would eventually be named Alzheimer’s disease. Before its formal identification, this insidious condition was often a silent, bewildering torment, its victims adrift in a fog of forgetfulness, their struggles dismissed as the inevitable weariness of old age.

Our story begins not in a sterile laboratory, but in the bustling, gas-lit streets of Germany in 1906. It was there, at a psychiatric clinic in Frankfurt, that Dr. Alois Alzheimer first encountered a patient whose case would etch his name into medical history. Auguste Deter, a middle-aged woman, was exhibiting a disturbing array of symptoms: profound memory loss, paranoia, confusion, and a startling decline in her ability to understand language. Her husband’s heartbreaking testimony, describing her as having lost herself, painted a grim picture of a mind unraveling long before its time.

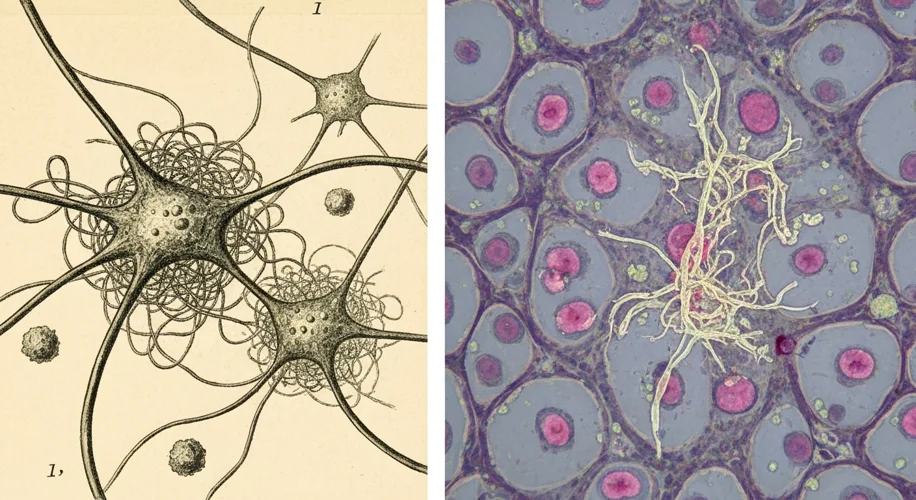

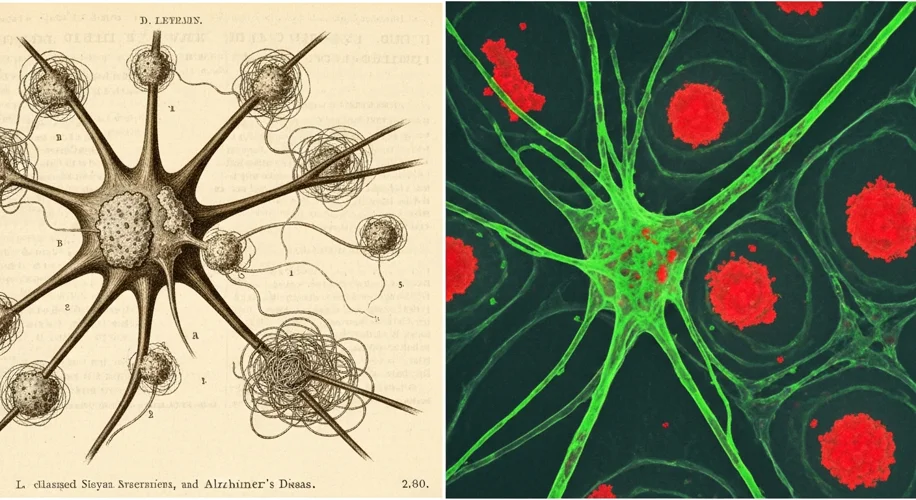

Dr. Alzheimer, a neuropathologist with a keen eye for the subtle alterations of the brain, was captivated by Auguste’s case. Unlike the more common forms of dementia seen in the elderly, her symptoms presented at a relatively younger age, hinting at a distinct, perhaps even novel, pathology. After her death, he meticulously examined her brain, a painstaking process in an era before advanced imaging. What he discovered were two key hallmarks: abnormal clumps, later known as amyloid plaques, accumulating outside nerve cells, and tangled fibers, or tau tangles, forming inside them. These were groundbreaking observations, but their significance would take decades to fully comprehend.

In the decades that followed Alzheimer’s initial discovery, the disease remained something of a medical enigma. While researchers like Dr. Oskar Fischer and Dr. Emil Kraepelin contributed to the understanding of the pathological changes, the prevailing view was that severe cognitive decline was simply a natural part of aging. The term “Alzheimer’s disease” itself wasn’t widely adopted until the 1970s, a testament to how long it took for this specific condition to be recognized as a distinct entity with unique causes and progression.

The mid-20th century brought a gradual shift. As lifespans increased and populations aged, the prevalence of dementia became more apparent. Yet, the path to understanding its molecular underpinnings was fraught with challenges. Theories about its causes ranged from vascular problems to infections, each met with varying degrees of evidence. The breakthrough came with the identification of the specific protein fragments that formed the amyloid plaques, a crucial step in unraveling the complex biochemistry of the disease.

The latter half of the 20th century and the dawn of the 21st century witnessed an explosion in Alzheimer’s research. Sophisticated diagnostic tools, including PET scans and advanced cerebrospinal fluid analysis, allowed for earlier and more accurate diagnoses, even distinguishing Alzheimer’s from other forms of dementia. This diagnostic progress was a double-edged sword: it brought clarity but also highlighted the growing number of individuals affected by this devastating illness.

Therapeutic approaches initially focused on managing symptoms, primarily through drugs that temporarily boosted levels of acetylcholine, a neurotransmitter crucial for memory and learning. While offering some relief, these treatments did not halt the disease’s relentless progression. The quest for disease-modifying therapies, those that could slow or stop the underlying pathological processes, became the holy grail of Alzheimer’s research.

This has led to a deep dive into the mechanisms of amyloid and tau pathology, with numerous experimental drugs targeting these proteins. Some have shown promise in clinical trials, offering glimmers of hope, while others have faced setbacks, underscoring the immense complexity of the brain and the disease’s multifaceted nature. Researchers are also exploring other avenues, including inflammation, genetics, and lifestyle factors, recognizing that a comprehensive approach is likely needed.

Today, in 2026, Alzheimer’s disease represents a significant global health challenge. It is a disease that not only robs individuals of their memories and cognitive abilities but also places an immense burden on families, caregivers, and healthcare systems. The journey from Dr. Alzheimer’s meticulous observations of Auguste Deter to the cutting-edge research of today is a testament to human perseverance and scientific curiosity. It is a story etched in the persistent struggle to understand and, ultimately, to conquer a disease that has cast a long shadow over the human experience, a shadow we are still striving to lift, one discovery at a time.