In the dimly lit salons and bustling intellectual centers of 18th-century Europe, a quiet revolution was brewing, not with swords and cannons, but with books and ideas. This was the Haskalah, or the Jewish Enlightenment, a movement that sought to bridge the ancient world of Jewish tradition with the surging currents of modern thought.

For centuries, Jewish life had been largely confined to the insular world of religious study and communal self-governance. The Talmud, the vast compendium of Jewish law and lore, was the intellectual cornerstone, shaping every facet of life. Yet, as the Enlightenment swept across Europe, challenging established norms and championing reason and secular knowledge, a yearning for change began to stir within some Jewish communities.

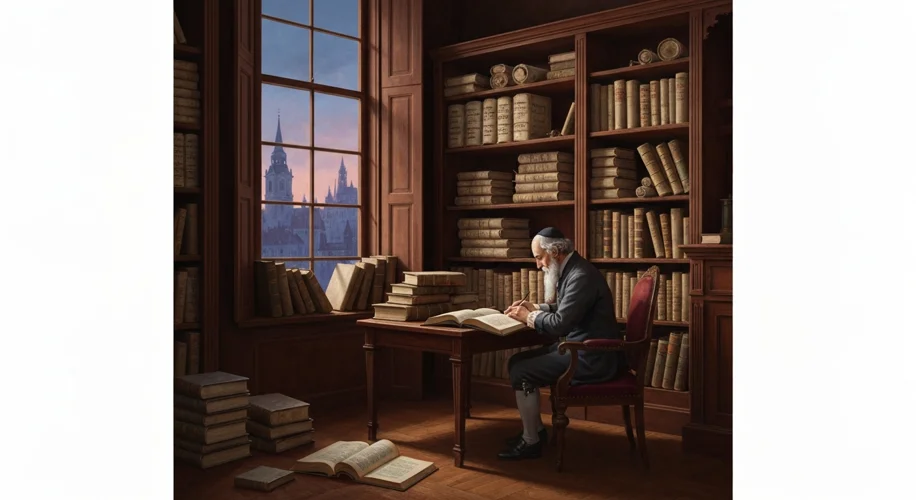

Imagine a young scholar, perhaps in Berlin or Königsberg, pores over Maimonides by candlelight, his mind steeped in centuries of legal debate. But outside his window, the air hums with new ideas – the philosophies of Kant, the burgeoning sciences, the rise of vernacular literature. A question begins to form: Can the rich heritage of Judaism not only coexist with this modern world but also be enriched by it?

This was the heart of the Haskalah. Spearheaded by figures like Moses Mendelssohn, a philosopher whose intellectual prowess earned him respect even among non-Jewish thinkers, the movement advocated for a revitalization of Jewish life. The goal was not to abandon tradition, but to integrate it with secular education, modern languages, and a more critical approach to texts. They believed that by engaging with the wider world, Jews could shed the stigma of perceived backwardness and achieve greater social and intellectual parity with their European neighbors.

The Haskalah was a multifaceted movement. Linguistically, it championed the use of Hebrew not just as a sacred tongue but as a vibrant language capable of expressing modern ideas, leading to a renaissance in Hebrew literature and journalism. German, and other European vernaculars, were embraced to facilitate access to secular knowledge and to engage in public discourse.

Socially, Haskalah proponents encouraged Jews to adopt European dress, manners, and professions, moving away from the distinct, often segregated, lifestyles that had characterized life in the Pale of Settlement or the ghettos of Western Europe. They established schools that taught both Jewish and secular subjects, aiming to produce a new generation of Jews who were both learned in their heritage and capable of thriving in the modern world.

Key actors of the Haskalah, beyond Mendelssohn, included figures like Rabbi Elijah ben Solomon Zalman, the Vilna Gaon, whose intellectual rigor, though sometimes critical of the Haskalah’s embrace of secularism, nonetheless exemplified the pursuit of deep learning. However, the movement was not without its internal debates and external challenges. Traditionalists often viewed the Haskalah with suspicion, fearing it would lead to assimilation and the erosion of Jewish identity. External pressures, including antisemitism and governmental restrictions, also posed significant obstacles.

The impact of the Haskalah was profound and far-reaching. It laid the groundwork for modern Jewish education, scholarship, and cultural expression. It contributed to the rise of Reform Judaism, which sought to adapt Jewish practice to modern sensibilities. It also, however, inadvertently created social and ideological divides within Jewish communities, as traditionalists and modernizers found themselves at odds.

The legacy of the Haskalah is a complex tapestry. It was a pivotal moment when Jewish thinkers grappled with modernity, seeking to preserve their heritage while embracing the future. It demonstrated the power of intellectual engagement to transform a people, leading to significant linguistic, social, and cultural changes that continue to resonate in Jewish life today. It stands as a testament to the enduring human drive to reconcile the old with the new, the sacred with the secular, in the ongoing quest for understanding and self-improvement.