When we hear the phrase “Scientific Revolution,” our minds often leap to the bustling intellectual salons of 17th-century Europe, to figures like Newton and Galileo. But history, in its vast tapestry, rarely offers such a singular narrative. Long before the European Renaissance ignited, a vibrant scientific tradition was flourishing in the Islamic world, a period of extraordinary innovation that laid crucial groundwork for the very revolution that would later eclipse it.

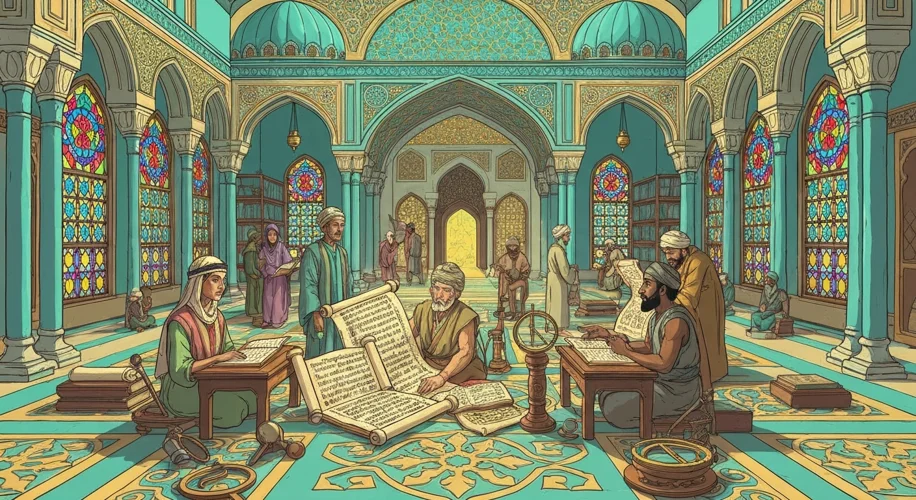

Imagine a world where Baghdad was the undisputed center of learning, a city whose House of Wisdom, established in the early 9th century, was a beacon attracting scholars from across continents. This wasn’t merely a library; it was a dynamic hub of translation, research, and discovery. Think of it as the ancient world’s ultimate think tank, where texts from Greece, Persia, India, and beyond were meticulously translated into Arabic, preserving and building upon centuries of human knowledge.

This intellectual ferment wasn’t confined to one discipline. In mathematics, scholars like Muhammad ibn Musa al-Khwarizmi, a Persian scholar who worked in Baghdad, gave us the very word “algebra” from his seminal work “Al-Jabr.” His systematic approach to solving linear and quadratic equations, and his introduction of Hindu-Arabic numerals (including the crucial concept of zero) to the West, fundamentally reshaped the landscape of numerical thought. His name, Latinized as Algoritmi, also gave us the word “algorithm” – a testament to his enduring legacy in computing and problem-solving today.

Astronomy, too, was a star. Observatories dotted the Islamic world, from Baghdad to Samarkand. Scholars like Al-Battani refined astronomical tables, corrected Ptolemy’s measurements, and made crucial observations about solar and lunar eclipses. They developed sophisticated instruments like the astrolabe, not just for telling time or predicting celestial events, but for navigation and even determining prayer times. The precision of their work, often challenging established Aristotelian and Ptolemaic models, demonstrated a commitment to empirical observation that would become a hallmark of later scientific inquiry.

Medicine in the Islamic Golden Age was nothing short of revolutionary. Figures like Ibn Sina (Avicenna), whose “Canon of Medicine” was a standard medical textbook in Europe for centuries, compiled vast amounts of medical knowledge. He described diseases like meningitis, identified the contagious nature of tuberculosis, and emphasized clinical trials and evidence-based practice. Hospitals were not just places for the sick; they were centers for medical training and research, offering specialized wards and sophisticated treatments. Al-Razi (Rhazes) famously differentiated between smallpox and measles, a diagnostic leap that saved countless lives.

Optics was another arena of remarkable achievement. Ibn al-Haytham (Alhazen), often hailed as the father of modern optics, revolutionized our understanding of vision. He correctly argued that vision occurs when light from an object enters the eye, not when the eye emits rays. His meticulous experiments with lenses and mirrors, detailed in his “Book of Optics,” laid the foundation for modern optics, the development of eyeglasses, and even principles used in cameras.

This era, roughly spanning the 8th to the 15th centuries, was characterized by a culture that deeply valued knowledge, regardless of its origin. The Abbasid Caliphate, in particular, actively sponsored translation projects, recognizing that scientific progress transcended religious and ethnic boundaries. This wasn’t just about preserving old texts; it was about actively engaging with them, questioning them, and pushing the boundaries of what was known.

The impact of this scientific flourishing was profound and far-reaching. The translations and original works of Islamic scholars gradually made their way into Europe, particularly through centers like Toledo in Spain, during the later Middle Ages. This infusion of knowledge played a critical role in sparking the European Renaissance and, subsequently, the Scientific Revolution. Without the meticulous translations, the refined mathematical concepts, and the empirical observations made by scholars in Baghdad, Cordoba, and Cairo, the trajectory of Western science might have been vastly different, and perhaps much slower.

It’s a poignant reminder that scientific progress is a global, cumulative endeavor. While the narrative often focuses on the dramatic breakthroughs of one region, it’s vital to acknowledge the deep roots and the rich soil from which those later blooms emerged. The Islamic Golden Age of Science stands as a testament to the power of curiosity, collaboration, and the relentless pursuit of understanding – a legacy that continues to illuminate our world.