In the heart of a world often perceived as steeped in conflict and conquest, a different kind of battle raged – a battle of ideas. From the bustling souks of Baghdad to the learned halls of Cordoba, an intellectual Renaissance bloomed between the 8th and 13th centuries, known as the Golden Age of Islamic Philosophy. This was not merely a period of religious devotion, but a vibrant era where reason and revelation intertwined, forging a legacy that continues to echo through the corridors of human thought.

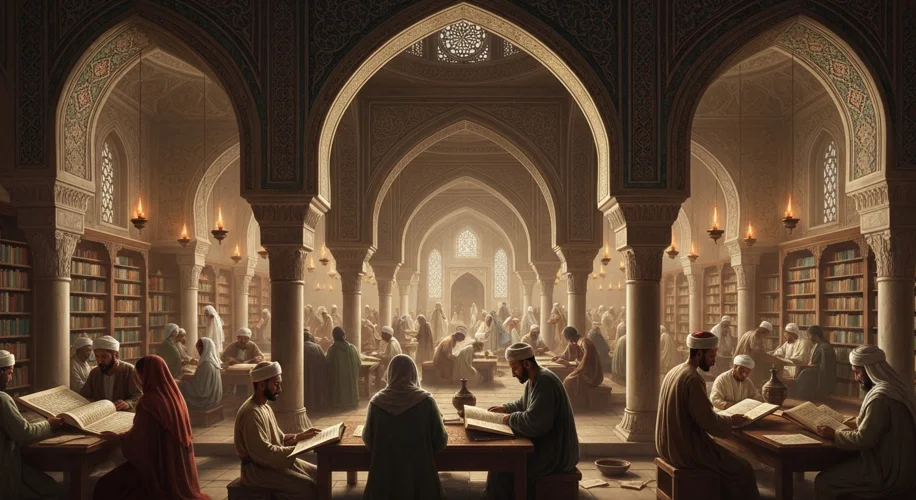

The stage was set in the Abbasid Caliphate, a dynasty that, after overthrowing the Umayyads in 750 CE, established Baghdad as its dazzling capital. This new empire, stretching from North Africa to Central Asia, became a magnet for scholars, artists, and thinkers. The caliphs, particularly Al-Ma’mun (reigned 813-833 CE), were not just rulers but patrons of knowledge. The establishment of the Bayt al-Hikma, or House of Wisdom, in Baghdad was a monumental undertaking. Imagine vast libraries filled with scrolls and manuscripts, where scholars from diverse backgrounds – Muslim, Christian, Jewish – gathered to translate, debate, and create.

This was a melting pot of ancient wisdom. Greek philosophical texts, once confined to dusty corners of the Byzantine Empire, were meticulously translated into Arabic. Plato, Aristotle, Galen – their ideas were not just preserved but re-examined, reinterpreted, and built upon. This act of translation was not a passive act of preservation; it was an active engagement, a conscious effort to understand the universe through the lens of reason, a faculty Islam itself championed.

Into this intellectual ferment stepped titans. Al-Kindi (c. 801–873 CE), often called the ‘Philosopher of the Arabs,’ was a polymath who embraced Aristotelian thought and synthesized it with Islamic theology. He explored everything from astronomy and medicine to music and mathematics, attempting to bridge the gap between faith and reason. He believed that philosophy was the highest form of human knowledge and that its pursuit was a path to understanding God’s creation.

Then came Al-Farabi (c. 872–950 CE), known as ‘The Second Teacher’ (after Aristotle). Al-Farabi delved deeper into Aristotelian metaphysics and political philosophy. His work, Al-Madina al-Fadila (The Virtuous City), envisioned an ideal state governed by a philosopher-king, echoing Plato’s Republic but infused with Islamic principles. He meticulously analyzed the relationship between prophecy and philosophy, suggesting that prophets were essentially philosophical leaders with a divine connection.

But perhaps the most towering figure of this era was Ibn Sina (Avicenna, c. 980–1037 CE). A prodigy who had mastered medicine and philosophy by his teenage years, Ibn Sina’s Canon of Medicine became a standard medical textbook in Europe for centuries. His philosophical masterpiece, The Book of Healing, provided a comprehensive system of Aristotelian and Neoplatonic thought, offering detailed explanations of logic, natural sciences, and metaphysics. His concept of the ‘Active Intellect’ profoundly influenced both Islamic and later Christian scholasticism.

As the centuries turned, the torch was passed to thinkers like Ibn Rushd (Averroes, 1126–1198 CE), who worked in the more heterodox, cosmopolitan environment of Al-Andalus (Islamic Spain). Ibn Rushd was a fierce defender of reason and Aristotelian philosophy. His commentaries on Aristotle were so influential that they were translated into Latin and became foundational texts for medieval European philosophers. He famously argued for the harmony of faith and reason, positing that religious texts should be interpreted allegorically if they contradicted philosophical truths. His bold stance, however, brought him into conflict with religious authorities, leading to the burning of his books and a temporary exile.

This intellectual flourishing was not confined to abstract thought. It fueled advancements in science, mathematics, medicine, and astronomy. Muslim astronomers in observatories like those in Baghdad and Samarkand meticulously charted the stars, refining astronomical models. Mathematicians developed algebra, a term derived from the Arabic al-jabr, and expanded the use of Hindu-Arabic numerals, including the concept of zero, which revolutionized calculation.

However, all golden ages eventually fade. By the 13th century, a combination of internal political fragmentation, external invasions (most notably the Mongol sack of Baghdad in 1258), and a growing orthodoxy that viewed philosophy with suspicion, led to a decline in this vibrant intellectual tradition. Yet, the legacy of this period is undeniable. The translations and commentaries produced by these scholars were crucial bridges for transmitting ancient Greek knowledge to medieval Europe, playing a pivotal role in the European Renaissance. Figures like Ibn Sina and Ibn Rushd shaped the very foundations of Western philosophical and scientific thought, their ideas debated and developed by giants like Thomas Aquinas.

The Golden Age of Islamic Philosophy serves as a powerful reminder that intellectual progress often thrives in periods of cultural exchange and open inquiry. It challenges simplistic narratives of history, showcasing a sophisticated and dynamic intellectual landscape within the Islamic world that profoundly shaped the trajectory of human knowledge. It was a time when the pursuit of understanding, whether through divine revelation or rational inquiry, was not just encouraged but celebrated as the noblest of human endeavors.