The year is 1945. The world has been engulfed in the fires of World War II for six long years. In the Pacific, the brutal island-hopping campaign between the United States and Japan has reached a horrifying crescendo. The battles for Iwo Jima and Okinawa have shown the American military the fierce, often suicidal, resistance of the Japanese forces. Casualties were mounting on both sides, painting a grim picture of what an invasion of the Japanese mainland might entail. Little did anyone know, a new, terrifying chapter of warfare was about to be written, one that would forever alter the course of human history.

Picture this: August 6, 1945. The sky over Hiroshima, a city of over 300,000 people, was a brilliant blue. Most of its inhabitants were going about their day, unaware of the singular B-29 bomber, the Enola Gay, soaring high above. Onboard, a new kind of weapon, a device born from the top-secret Manhattan Project, was ready to be unleashed. The bomb, codenamed ‘Little Boy,’ was a uranium-based atomic bomb, a monstrous creation of immense power.

At 8:15 AM, ‘Little Boy’ was released. The world held its breath, though most in Hiroshima had no idea what was coming. The bomb detonated about 1,900 feet above the city center. The immediate effect was cataclysmic. An intensely bright flash, hotter than the surface of the sun, seared the earth. A monstrous mushroom cloud, a terrifying testament to the unleashed power, billowed upwards. Within moments, the cityscape of Hiroshima was reduced to rubble and ash.

An estimated 70,000 to 80,000 people died instantly. Many more suffered horrific burns, their skin sloughing off, their bodies twisted into grotesque shapes. The heat was so intense that shadows were permanently etched onto walls and even on the bodies of victims – a chilling memento mori. Over the following weeks, months, and years, tens of thousands more succumbed to injuries and the insidious effects of radiation sickness, their bodies ravaged from within by invisible waves of energy.

The United States, under President Harry S. Truman, had made the fateful decision to use this new weapon. The justification was to force Japan’s swift surrender and avoid the devastating casualties expected from a land invasion. Japan, however, remained defiant, still clinging to the hope of a negotiated peace that would preserve their emperor system.

Three days later, on August 9, 1945, the B-29 bomber Bockscar dropped a second atomic bomb, ‘Fat Man,’ a plutonium-based device, on Nagasaki. The city was also devastated, though the rugged terrain somewhat mitigated the bomb’s full destructive potential compared to Hiroshima. The Nagasaki bombing claimed the lives of an estimated 40,000 people immediately, with tens of thousands more dying in the aftermath from radiation-related illnesses.

The impact of these two events was profound and immediate. Faced with the unprecedented destruction and the terrifying prospect of further atomic attacks, Japan’s leadership finally capitulated. On August 15, 1945, Emperor Hirohito announced Japan’s unconditional surrender, bringing an end to World War II.

The decision to use the atomic bomb remains one of the most debated and controversial in history. Proponents argue that it saved countless lives by preventing a bloody invasion of Japan, a notion supported by projections of Allied casualties that could have reached hundreds of thousands, if not millions. They point to the fierce resistance encountered on islands like Okinawa, where kamikaze attacks and civilian involvement in defense were commonplace, suggesting a similar fate for the Japanese mainland.

However, critics question whether the second bombing of Nagasaki was truly necessary. Some historians suggest that Japan was already on the verge of surrender, and that the Soviet Union’s declaration of war on Japan on August 8th might have been a more significant factor. Others raise moral and ethical questions about the targeting of civilian populations and the long-term humanitarian consequences, including the devastating effects of radiation that continued to plague survivors for decades.

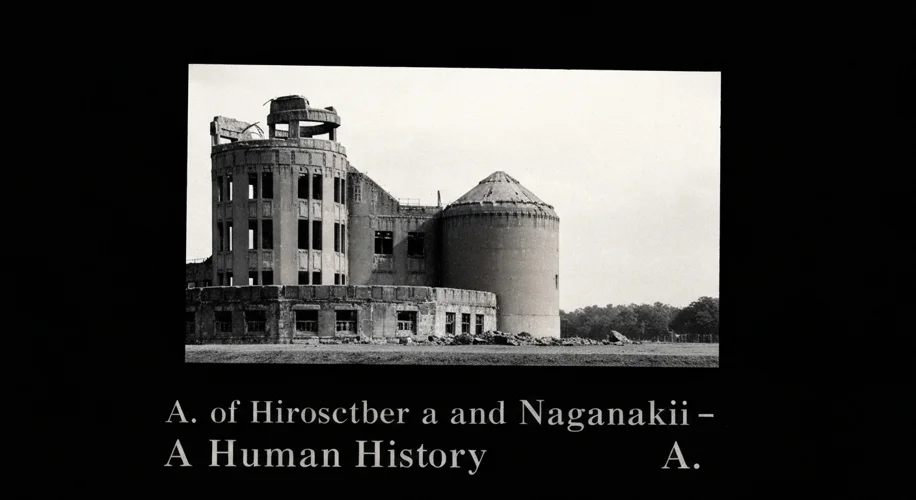

The bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki ushered in the Atomic Age, a new era defined by the existential threat of nuclear annihilation. They spurred a global arms race, shaping international relations and leading to the doctrine of Mutually Assured Destruction (MAD). The legacy of these events is a somber reminder of the terrible destructive power of modern weaponry and a perpetual call for peace, a plea echoed in the rebuilt cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, which now stand as powerful symbols of resilience and a testament to the enduring hope for a world free from the shadow of nuclear war.

As we look back from today, August 3, 2025, the echoes of those fateful days in August 1945 continue to resonate, urging us to remember the price of war and the vital importance of diplomacy and understanding.