Consider the following scenario: the year is approximately 1274 BC. The scorching sun beat down on the dusty plains near the Orontes River in what is now Syria. On one side, the mighty Egyptian Empire, led by the charismatic and ambitious Pharaoh Ramesses II, advanced with four divisions of chariots and infantry, a force designed to project Egyptian dominance deep into enemy territory. On the other, the formidable Hittite Empire, commanded by King Muwatalli II, lay in wait, their own formidable army, particularly their renowned war chariots, a potent threat.

This was the stage for the Battle of Kadesh, a clash of titans that would become one of the most documented and analyzed battles of the ancient world, primarily thanks to the Egyptians themselves. Ramesses II, eager to secure and expand his empire’s northern borders and reclaim lost territories from the Hittites, marched his army north. His goal: the strategically vital city of Kadesh, a prize coveted by both superpowers.

The Egyptian army was organized into four divisions, each named after a prominent Egyptian god: Amun, Re, Ptah, and Set. Ramesses, leading the Amun division, was confident, perhaps overly so. He believed he had outmaneuvered the Hittites, capturing some Hittite scouts who, under interrogation (likely torture), falsely claimed the Hittite army had retreated far to the north. Little did Ramesses know, this was a cunning deception.

The Hittite plan was audacious. Muwatalli II had amassed a large army, reportedly around 50,000 men, and crucially, their elite chariotry. While the Egyptian Amun and Re divisions were marching separately, with the Ptah division further behind and the Set division scattered, Muwatalli launched a swift and devastating surprise attack. Hittite chariots, a faster and more agile force than the heavier Egyptian counterparts, crashed into the unsuspecting Re division, scattering them and cutting off their retreat.

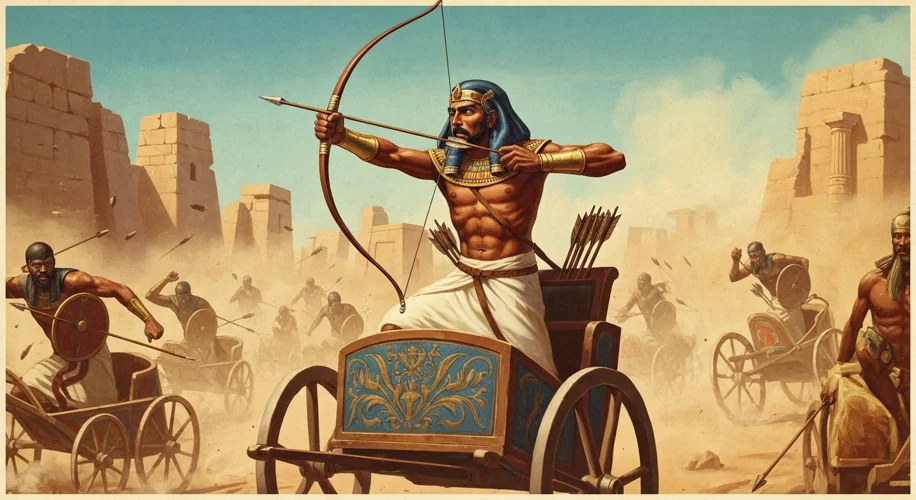

The air hung heavy with the screams of men and the thunder of hooves as the Hittite chariots overwhelmed the Re division. Ramesses, in the Amun division, found himself in a desperate situation. His flank was exposed, and the Hittite forces were pressing their advantage, attempting to encircle him. The Pharaoh, displaying remarkable personal bravery, rallied his remaining troops. He personally led charges against the Hittite onslaught, fighting from his chariot alongside his men. Accounts, heavily embellished by Ramesses’ own propaganda, describe him as being almost single-handedly responsible for repelling the Hittite advance.

As the day wore on, the battle became a chaotic mêlée. The arrival of the Egyptian Ptah division, along with a contingent of Canaanite allies who had been foraging, bolstered the Egyptian lines and forced the Hittites to regroup. The battle was fiercely contested, with neither side able to gain a decisive advantage. As night fell, the armies remained locked in a brutal stalemate. Muwatalli II, having failed to destroy the Egyptian army, withdrew his forces.

The immediate aftermath was presented by Ramesses II as a glorious victory. His temples and monuments were adorned with vivid reliefs depicting his personal valor and the complete annihilation of the Hittite army. However, the reality was far more complex. While the Egyptians had survived a near-catastrophic ambush, they had not achieved their objective of capturing Kadesh. The Hittites, though repulsed, had inflicted significant damage and demonstrated their military prowess.

The Battle of Kadesh, despite its inconclusive military outcome, had profound long-term consequences. It marked the end of Egypt’s aggressive expansion into Hittite territory and signaled a shift in the geopolitical balance of power in the Near East. Both empires, having suffered heavy losses, recognized the futility of continued conflict. The sheer brutality and the heavy cost of the battle likely paved the way for what is considered the first known international peace treaty in history, signed between Ramesses II and the Hittite King Hattusili III (Muwatalli II’s successor) around 1259 BC. This treaty established a lasting peace, mutual defense, and defined borders, ushering in a period of relative stability.

Analyzing the Battle of Kadesh offers a fascinating glimpse into ancient warfare. The detailed Egyptian accounts, particularly the ‘Poem of Pentaur’ and the reliefs at Karnak and Abu Simbel, provide invaluable, albeit biased, insights into formations, tactics, and the psychological impact of battle. It highlights the critical role of intelligence, the devastating potential of chariot warfare, and the immense personal leadership required of ancient rulers. The battle stands as a testament to the resilience of Ramesses II and the military might of both the Egyptian and Hittite empires, ultimately leading to a diplomatic resolution that reshaped the ancient world.