Imagine a world where opening a door requires a moment of intense concentration. Do you push? Pull? Slide? What if the handle offered no clue, and the mechanism itself seemed designed to confound? This frustrating, all-too-common reality is precisely what Don Norman set out to change.

In the annals of design, few figures loom as large as Don Norman. His seminal 1988 book, ‘The Design of Everyday Things,’ wasn’t just a book; it was a declaration of independence for the user. Before Norman, good design was often seen as an aesthetic luxury. He argued, with compelling clarity, that it was a fundamental necessity, deeply intertwined with how we interact with the world around us.

Norman, a cognitive psychologist by training, approached design from a unique vantage point: the human mind. He observed that many of the objects we use daily – from teapots to light switches – were designed without a clear understanding of how people actually think and behave. This gap between intention and execution led to what he famously termed ‘usability problems.’

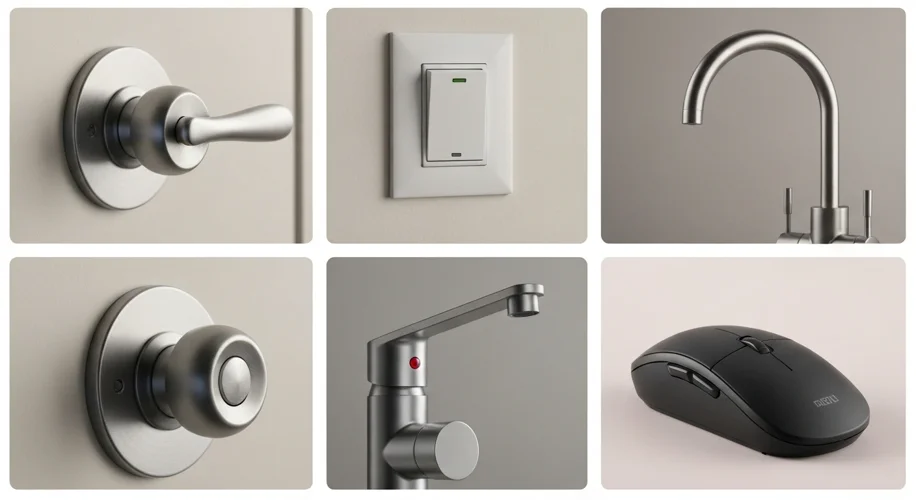

Think of the classic “Norman Door.” These are doors that, despite their appearance, operate in the opposite way you expect. A large, inviting handle might suggest pulling, but the door actually pushes open. This isn’t a minor inconvenience; it’s a failure of design, a communication breakdown between object and user. Norman meticulously cataloged these failures, attributing them to a lack of “affordances” and “signifiers.” Affordances are the properties of an object that suggest how it can be used (a handle affords pulling). Signifiers are the visible cues that communicate those affordances (a label saying “Pull”).

Norman’s work highlighted a critical shift in thinking about technology and objects. Instead of expecting users to adapt to the machine, he championed the idea that machines should be designed to adapt to the user. This user-centered approach, or “human-centered design” as he also termed it, was revolutionary. It placed the person interacting with the product at the absolute core of the design process.

His book provided a vocabulary for discussing these issues. Concepts like “visibility” (knowing what actions are possible and what state the system is in), “feedback” (seeing the results of your actions), and “mapping” (the relationship between controls and their effects) became essential tools for designers. He argued that good design should be intuitive, making the intended use obvious without explicit instruction. The goal was to create systems that were not only functional but also a pleasure to use, reducing frustration and cognitive load.

The impact of ‘The Design of Everyday Things’ has been profound. It moved beyond the realm of industrial design and into software, web design, and even service design. The principles Norman articulated are now foundational to user experience (UX) design. Companies that once prioritized sheer technical capability or aesthetic flair began to understand that a product’s success often hinges on how easily and effectively people can use it.

Consider the evolution of the smartphone. Early mobile phones were notoriously difficult to navigate, with complex button sequences and cryptic menus. Norman’s principles, implicitly or explicitly, guided the development of the touchscreen interface – a paradigm shift that made powerful computing accessible to billions. The clear visual cues, direct manipulation, and immediate feedback offered by touchscreens are direct descendants of Norman’s usability insights.

In essence, Don Norman’s ‘The Design of Everyday Things’ ignited a usability revolution. It empowered consumers to expect more from the products they interacted with daily and provided designers with the framework to deliver it. His work reminds us that the most advanced technology is only truly revolutionary when it seamlessly integrates into our lives, a testament to the power of thoughtful, human-centered design.