In the annals of technological marvels, few machines loom as large as the ENIAC – the Electronic Numerical Integrator and Computer. Unveiled to a world teetering on the brink of victory in World War II, this colossal electronic brain was more than just a collection of vacuum tubes and wires; it was a harbinger of the digital revolution, a testament to human ingenuity under pressure.

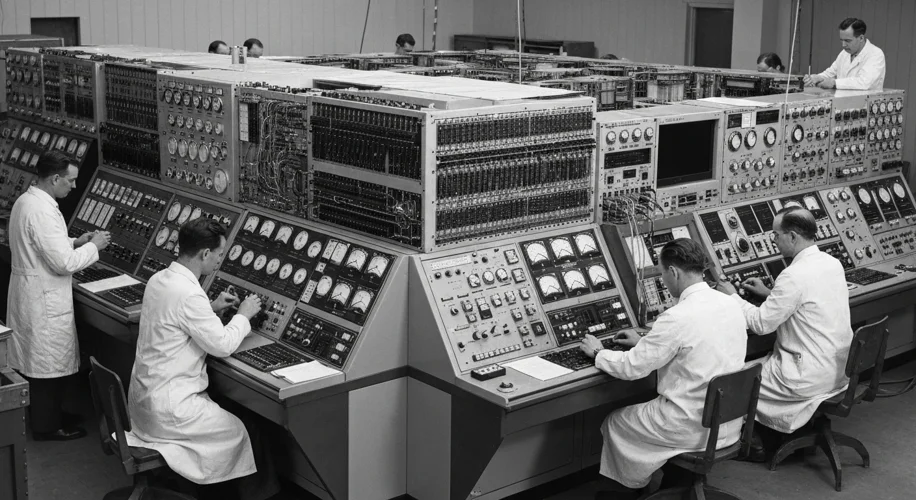

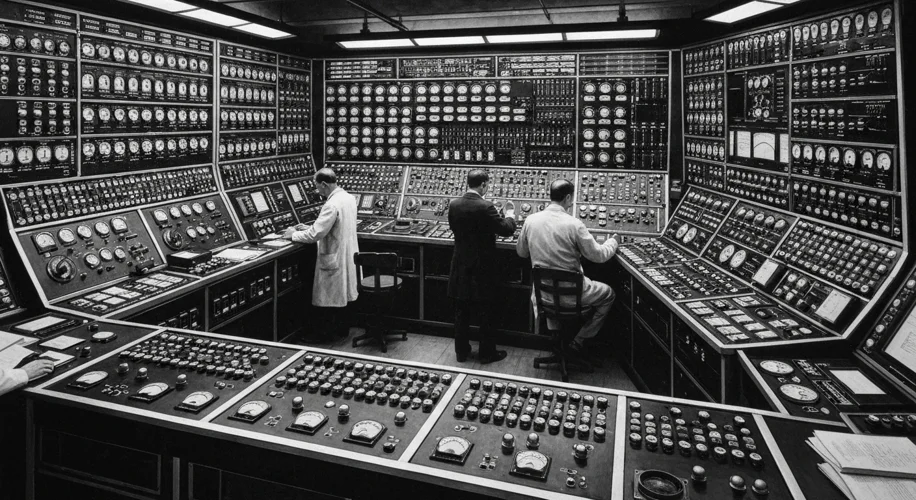

Imagine a room, vast and humming with an unseen power. Inside, a labyrinth of towering consoles, bristling with dials, switches, and blinking lights, stretched as far as the eye could see. This was the ENIAC, a behemoth that occupied a staggering 1,800 square feet and weighed a hefty 30 tons. It was the world’s first general-purpose electronic digital computer, a machine so groundbreaking it felt plucked from the pages of science fiction.

The genesis of ENIAC lay in the urgent demands of the Second World War. The Allied forces desperately needed to calculate complex artillery firing tables, a task that was agonizingly slow and prone to human error when performed manually. These tables were critical for accurately directing artillery fire, and the speed and precision offered by an electronic computer were paramount. The task was so monumental that it would take a team of mathematicians, often referred to as ‘computers’ (because they computed!), weeks to produce a single table. The United States Army recognized this bottleneck and sought a solution that could accelerate this process dramatically.

Thus, in 1943, the collaboration between the University of Pennsylvania and the U.S. Army Ordnance Corps began, leading to the creation of ENIAC. The minds behind this revolutionary machine included John Mauchly and J. Presper Eckert, whose vision and engineering prowess transformed abstract concepts into a tangible, albeit immense, reality. They faced immense challenges, not least of which was the unreliability of the vacuum tubes, which were the building blocks of early electronics. ENIAC contained a staggering 17,468 vacuum tubes, and engineers had to anticipate and replace faulty tubes with astonishing regularity – sometimes several per day.

The sheer scale of ENIAC’s operation was unlike anything seen before. It consumed a formidable 150 kilowatts of power, enough to light up a small town. Its intricate wiring involved over 40,000 custom-built resistors, 10 million soldered joints, and miles of electrical cable. Programming ENIAC was a Herculean effort in itself. Instead of modern software,