Before the ink dried on the New Deal, a more insidious blueprint for segregation was already being drawn across the American landscape. This wasn’t a policy born of economic crisis, but a deep-seated prejudice that carved up neighborhoods, dictating where citizens could live, thrive, or even be seen. This was the era of “redlining,” a practice that predates the federal government’s overt involvement but whose roots burrowed deep into the American psyche, laying the groundwork for decades of systemic inequality.

The seeds of this segregation were sown in the aftermath of the Civil War and the Reconstruction era. As Black Americans gained newfound freedoms, white communities, particularly in the South but also spreading to urban centers across the nation, sought to reassert control. This manifested in various forms of discrimination, including the rise of restrictive covenants – private agreements written into property deeds that prohibited the sale or rental of homes to Black people and other minority groups. These covenants, though privately enforced, painted a grim picture of a society determined to maintain racial hierarchies.

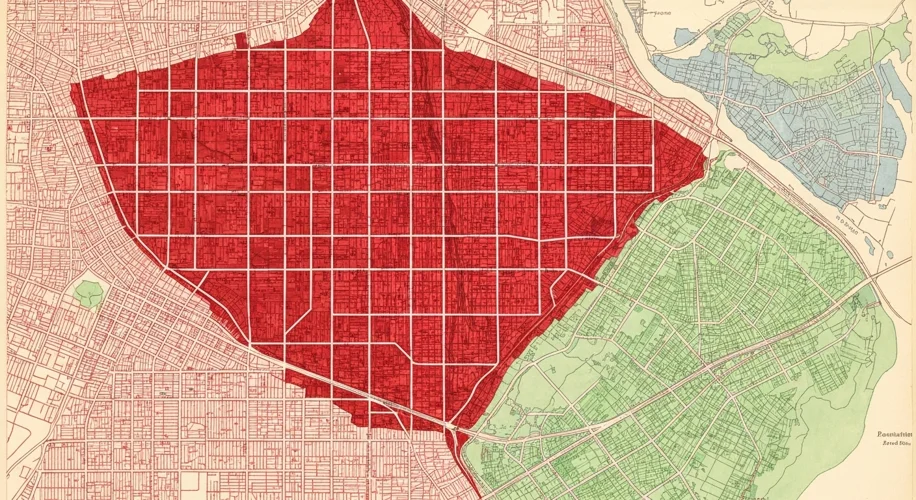

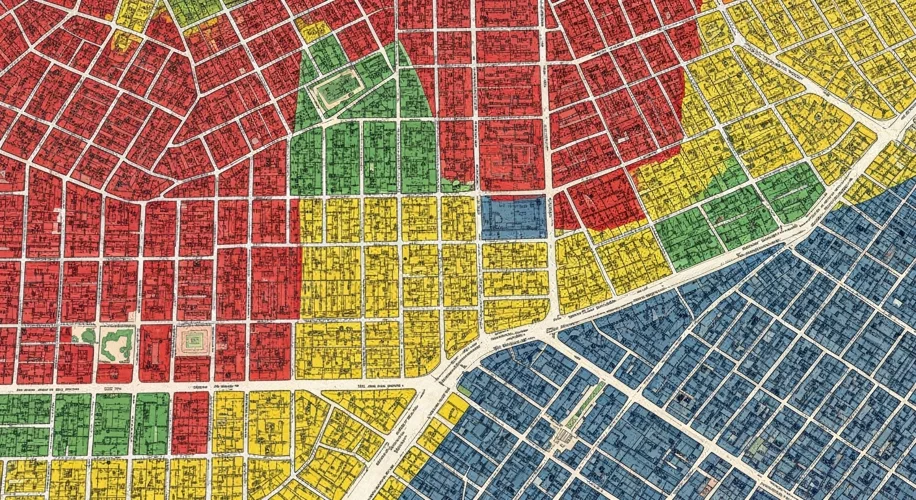

One of the most significant architects of this early, informal segregation was the American housing industry itself, particularly through the Federal Home Loan Bank Board (FHLBB) and later the Federal Housing Administration (FHA). While the New Deal era is often associated with these institutions, their foundational policies were built upon a pre-existing structure of racial bias. The FHA, established in 1934, aimed to stabilize the housing market and make homeownership more accessible. However, its appraisal manuals and underwriting guidelines actively incorporated racial prejudice. Neighborhoods with Black residents were systematically deemed “hazardous” – colored in red on maps created by the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC) and later by private lenders.

These “redlined” areas were not just deemed risky for investment; they were actively starved of capital. Banks and mortgage lenders refused to issue loans or offered them on punitive terms in these neighborhoods. This created a devastating feedback loop: lack of investment meant deteriorating infrastructure, fewer amenities, and limited economic opportunities. Consequently, property values stagnated or declined, further solidifying the perception of these areas as undesirable and reinforcing the cycle of disinvestment.

The impact was profound and far-reaching. For African Americans and other minority groups, redlining meant being systematically excluded from the burgeoning suburban dream that became synonymous with the post-war American prosperity. They were often relegated to overcrowded, under-resourced urban centers, while white families, thanks to government-backed mortgages and discriminatory practices, could access safer neighborhoods with better schools and more amenities. This denial of access to capital and opportunity created a stark wealth gap that persists to this day.

Historians and sociologists point to the early 20th century, particularly the 1920s and 1930s, as the period when these practices became codified, even before explicit federal legislation. Real estate agents, appraisers, and lenders operated under a shared, unspoken understanding, reinforced by industry publications and appraisal guides. The National Association of Real Estate Boards, for example, had a code of ethics that included a commitment to maintaining the racial homogeneity of neighborhoods. This was not merely a matter of personal preference; it was a concerted effort to maintain social and economic segregation.

While the Fair Housing Act of 1968 officially outlawed redlining, its legacy continues to cast a long shadow. The disinvestment that characterized redlined communities left them with a legacy of urban decay, poverty, and limited access to resources. The wealth gap created by decades of discriminatory lending practices remains one of the most significant challenges facing the United States. Understanding the genesis of redlining, therefore, is not just an academic exercise; it is crucial to grasping the deep historical roots of contemporary racial and economic inequality in America.

The story of redlining is a stark reminder that discrimination often wears many masks. Before it became a federally sanctioned policy, it was a pervasive, yet often unacknowledged, practice embedded in the very fabric of American society, shaping its cities and its people in ways that continue to resonate today.