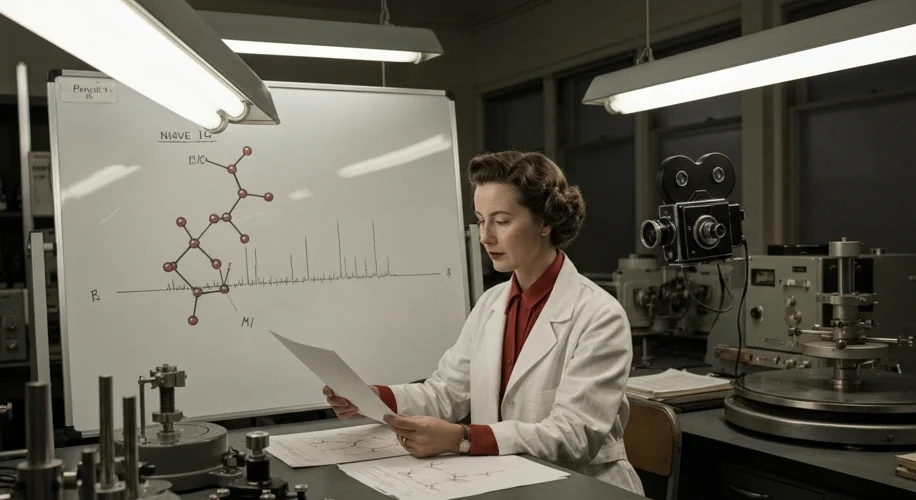

In the annals of scientific discovery, some names shine with a particular brilliance, illuminating not just the intricate structures of molecules but also the dedication and perseverance of the human spirit. One such luminary was Dorothy Hodgkin, a British biochemist whose pioneering work in X-ray crystallography unlocked the three-dimensional secrets of some of life’s most vital molecules.

Born Dorothy Mary Crowfoot in Cairo, Egypt, on May 12, 1910, Hodgkin’s early life was shaped by her parents’ academic pursuits. Her father was an inspector of schools in Sudan, and her mother was an expert in ancient Egyptian textiles. This blend of intellectual curiosity and appreciation for intricate detail would serve her well. As a child, she displayed a remarkable aptitude for chemistry, a passion that was further nurtured by her parents and early mentors.

However, the path to a scientific career for women in the early 20th century was far from smooth. Hodgkin faced societal expectations that often steered women away from rigorous academic pursuits. Yet, her resolve was unwavering. She attended Somerville College, Oxford, in 1928, where she studied chemistry. It was during this time that she encountered the burgeoning field of crystallography, a technique that uses the diffraction of X-rays to determine the atomic and molecular structure of a crystal. The potential of this method to reveal the hidden architecture of matter captivated her.

Her postgraduate work at Cambridge under the tutelage of John Desmond Bernal, a pioneer in X-ray crystallography, further honed her skills. Bernal recognized her talent and encouraged her to focus on biological molecules, a notoriously challenging area for crystallography. Upon returning to Oxford in 1934, Hodgkin established her own research group and began tackling some of the most complex molecular structures of her time.

The mid-20th century was a golden age for understanding the building blocks of life, and Hodgkin was at its forefront. Her magnum opus was the determination of the structure of penicillin, completed in 1945. This was a monumental achievement, as it confirmed the molecular structure of the antibiotic that had revolutionized medicine. During World War II, penicillin was a scarce and vital resource, and knowing its precise structure was crucial for its efficient production and development. Hodgkin’s work directly contributed to this effort, cementing her place in scientific history.

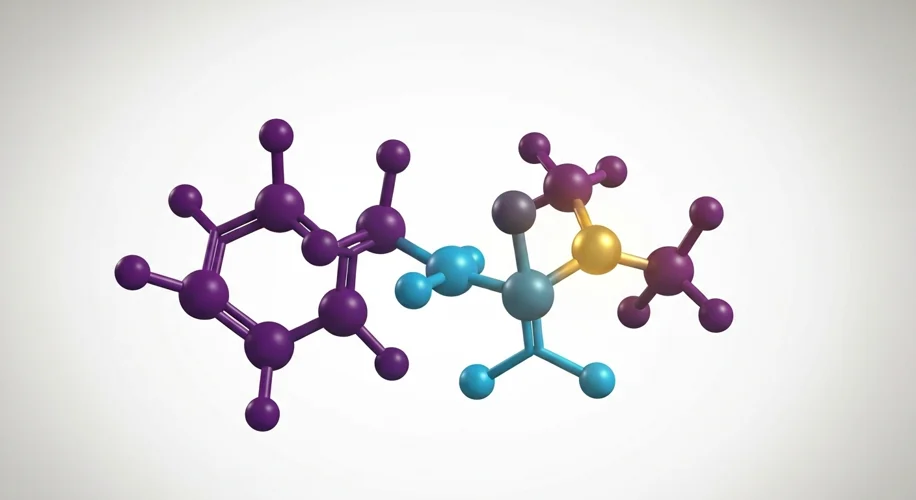

But her greatest triumph, the one that would earn her the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1964, was elucidating the structure of vitamin B12. This molecule, essential for nerve function and the formation of red blood cells, was incredibly complex, containing a large number of atoms arranged in a precise three-dimensional configuration. For years, scientists had struggled to decipher its structure. Hodgkin and her team, using painstaking X-ray diffraction analysis and employing advanced computing techniques for the time, finally cracked the code. Their determined structure, published in 1957, was a masterpiece of scientific deduction and experimental rigor. It revealed a molecule of astonishing intricacy, with a cobalt atom at its heart, surrounded by a complex ring system.

Beyond these landmark discoveries, Hodgkin also made significant contributions to understanding the structure of cholesterol, a molecule linked to heart disease, and the structure of the antibiotic cephalosporin. Her work on insulin, initiated in the 1930s, spanned decades and was finally completed in 1969, providing crucial insights into the structure of this vital hormone that regulates blood sugar.

Hodgkin’s approach was characterized by a relentless pursuit of accuracy and a deep respect for the experimental data. She famously stated, “The structure is there, and it is our job to find it.” She was known for her meticulous attention to detail, her quiet determination, and her ability to inspire and lead her research team. She was not only a brilliant scientist but also a dedicated mentor, fostering the careers of many young crystallographers.

Her impact extended beyond the laboratory. Hodgkin was a passionate advocate for science and its role in society. She served as President of the Pugwash Conferences on Science and World Affairs, an organization that promotes dialogue between scientists to address global security issues. She believed that science should be used for the betterment of humanity and was a vocal proponent of nuclear disarmament.

Dorothy Hodgkin’s legacy is profound. She not only revealed the molecular architecture of life’s most essential compounds but also paved the way for future advancements in medicine, genetics, and biochemistry. Her determination in the face of societal barriers and her unwavering commitment to scientific truth serve as an enduring inspiration. She showed the world that with persistence, intellect, and a deep understanding of the fundamental principles of nature, even the most complex molecular mysteries can be solved, one X-ray at a time.

Her work on penicillin and vitamin B12, in particular, had direct and lasting impacts on medicine. Understanding the precise structure of penicillin allowed for its mass production, saving countless lives during and after World War II. Similarly, the elucidation of vitamin B12’s structure was critical for diagnosing and treating pernicious anemia and other related neurological disorders. These weren’t abstract academic exercises; they were discoveries that directly alleviated human suffering.

Dorothy Hodgkin passed away on July 29, 1994, leaving behind a legacy that continues to shape our understanding of the biological world. She was a pioneer, a visionary, and a testament to the power of scientific inquiry. Her story reminds us that behind every breakthrough, there is a human journey of dedication, resilience, and an unyielding quest for knowledge.