The Soviet Union, a colossal ideological project built on the bedrock of Marxism-Leninism, cast a long and complex shadow over the 20th century. While its own literary output often served as a powerful propaganda tool, the USSR’s engagement with world literature was a far more nuanced affair. It was a carefully curated dance, a strategic embrace and a cautious rejection, all aimed at bolstering the socialist ideal and maintaining ideological control.

The Soviet approach to foreign literature was inextricably linked to the tumultuous historical currents of its birth and evolution. Emerging from the ashes of Tsarist Russia, the Bolsheviks saw literature as a vital weapon in their class struggle. Initially, there was a revolutionary fervor to embrace all forms of anti-bourgeois thought, leading to a period of relative openness. Writers like Upton Sinclair, with his muckraking critiques of American capitalism, found fertile ground in the Soviet Union. The early years saw translations and distribution of works that exposed social inequalities and championed the plight of the working class.

However, this honeymoon period was short-lived. As the Soviet state consolidated power under Stalin, the concept of socialist realism became the dominant aesthetic. This meant literature, both domestic and foreign, had to conform to a strict ideology, portraying Soviet life in an idealized, heroic light. Foreign works that didn’t fit this mold were often banned, suppressed, or heavily censored. The aim was to present a unified, unwavering vision of Soviet progress, and anything that challenged this narrative was a threat.

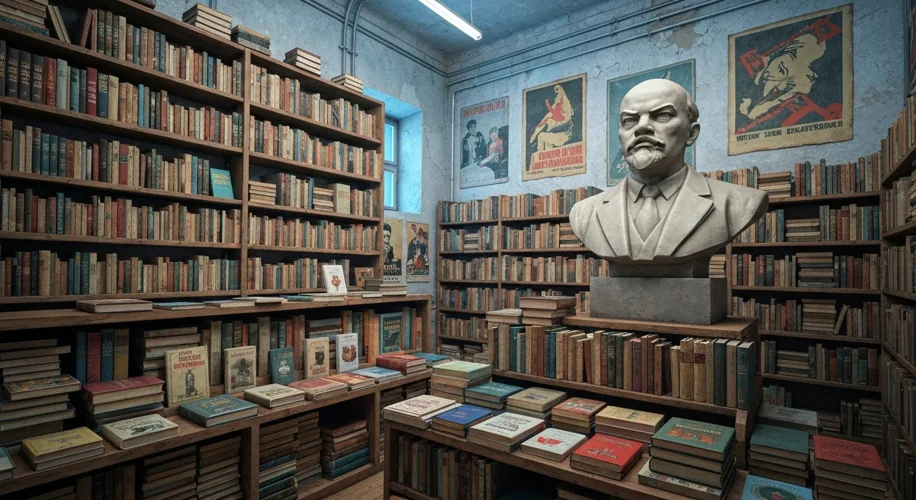

The key actors in this grand literary theatre were the state-controlled publishing houses, literary journals, and translation institutes. These bodies acted as gatekeepers, deciding which foreign authors would be introduced to Soviet readers and in what form. Figures like Maxim Gorky, initially a celebrated proponent of revolutionary literature, later found himself navigating the increasingly restrictive artistic landscape. Writers and intellectuals who had lived abroad, such as Maxim Gorky himself, played a crucial role in bridging the gap, though often under immense pressure to align their own interpretations with the prevailing Soviet dogma.

Consider the Soviet reception of Western literary giants. Ernest Hemingway, whose rugged individualism and terse prose initially appealed to the Soviet fascination with strength and action, was celebrated for his anti-war sentiments and his portrayals of working-class heroes. His novels, like “For Whom the Bell Tolls,” resonated with the Soviet anti-fascist narrative. Similarly, Jack London, with his tales of survival and struggle against nature, was a popular figure, his themes of overcoming adversity aligning with the Soviet emphasis on resilience.

However, writers who critiqued Soviet ideology or offered a more complex, less ideologically pure view of the world often met a different fate. George Orwell’s “Animal Farm” and “Nineteen Eighty-Four,” with their thinly veiled allegories of Soviet totalitarianism, were strictly forbidden for decades. The very idea that a Western author could expose the flaws of the Soviet system was anathema.

The Soviet Union also engaged in a form of literary appropriation, selectively translating and promoting works that served its political agenda. For instance, while American capitalist writers were largely shunned, writers like John Steinbeck, whose “The Grapes of Wrath” depicted the struggles of the Great Depression, found a sympathetic audience. His depiction of hardship in America provided a counter-narrative to the idealized image of Western prosperity.

The impact of this curated engagement was profound. It shaped the intellectual landscape of the Soviet Union, providing a selective window onto the world. For many Soviet citizens, these translated works were their primary, and often only, exposure to diverse political and philosophical ideas. This could lead to a complex understanding of global affairs, filtered through the Soviet lens. It also fueled a hidden hunger for uncensored ideas, leading to the widespread circulation of banned books through samizdat (self-published) networks.

Analyzing Soviet engagement with world literature reveals a fascinating duality. On one hand, it was a powerful tool of ideological containment and propaganda, carefully controlling the flow of information to maintain the sanctity of the socialist project. On the other hand, it inadvertently fostered a critical consciousness among some readers, planting seeds of doubt and curiosity that would later contribute to the intellectual ferment leading to the USSR’s eventual dissolution. The Soviet Union sought to use world literature as a mirror to reflect its own ideals, but in doing so, it also allowed glimpses of worlds that challenged those very ideals, creating a legacy of literary engagement that was as complex and contradictory as the state itself.