The year 1591 CE, or 1000 AH (Anno Hegirae) in the Islamic calendar, marked a profound millennial transition for a vast and diverse Islamic world. This was not a singular, monolithic event, but rather a tapestry woven from countless local celebrations, intellectual reflections, and spiritual endeavors across continents. From the bustling souks of Cairo to the scholarly centers of Ottoman Istanbul, the turn of the Islamic millennium was a moment of deep introspection and vibrant cultural expression.

The Islamic calendar, initiated with the Hijra (the migration of Prophet Muhammad from Mecca to Medina) in 622 CE, inherently frames time around a pivotal historical and spiritual event. Reaching the 1000 AH mark was therefore imbued with a unique significance, echoing the millennial sentiments felt in other parts of the world during similar historical junctures. It invited a reckoning with the past millennium and contemplation of the future, all within a rich framework of Islamic theology, philosophy, and scientific inquiry.

Across the vast Ottoman Empire, which at its zenith stretched from the Balkans to North Africa and the Middle East, the millennium was likely observed with a blend of official pronouncements and popular observances. Sultans, as Caliphs, held a symbolic position as leaders of the faithful, and such a significant temporal milestone would have been a moment to project power, piety, and continuity. Scholarly circles would have engaged in discussions about the cyclical nature of history, the fulfillment of prophecies, and the progress of Islamic sciences. While grand, empire-wide festivals might not have been explicitly documented in the same way as modern celebrations, the intellectual and religious life of the empire would undoubtedly have been animated by this transition.

In Safavid Persia, a different cultural and theological landscape prevailed, but the millennial shift would have still resonated. The Shi’a traditions would have lent a distinct flavor to the reflections, perhaps focusing on the anticipation of the return of the Hidden Imam or examining the historical trajectory of Shi’a Islam. Cities like Isfahan, then a burgeoning imperial capital, would have been centers of artistic and architectural patronage, and any major celebration or scholarly discourse surrounding 1000 AH would likely have been reflected in the city’s magnificent mosques and palaces.

Further east, in the Mughal Empire of India, the millennial celebrations would have been influenced by a rich syncretism of Persian, Turkic, and Indian cultural traditions. Emperors like Akbar, known for his intellectual curiosity and patronage of diverse religious thought, might have engaged with the millennium through philosophical debates or imperial decrees that acknowledged the passage of time and the divine mandate of their rule. The grand architectural projects and the flourishing of Urdu literature during this period would have provided a magnificent backdrop for any reflections on a thousand years of Islamic history.

Beyond the great empires, in regions like North Africa, Central Asia, and the Indian Ocean trade networks, local communities would have marked the occasion in their own ways. For many, it would have been a time for intensified prayer, increased charitable giving, and the recitation of the Quran. Sufi orders, with their emphasis on mystical experience and the spiritual journey, might have incorporated the millennial transition into their devotional practices, perhaps seeing it as a moment of heightened spiritual awareness or a harbinger of esoteric truths.

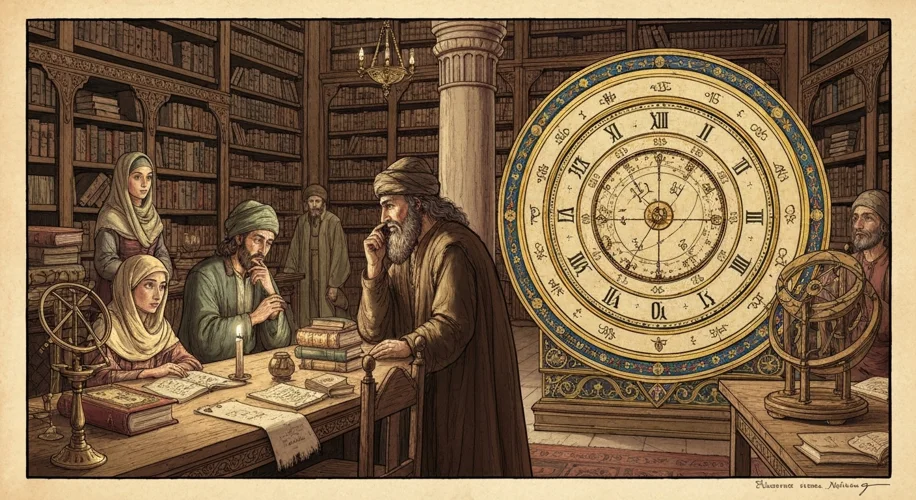

The intellectual achievements of the Islamic Golden Age, though perhaps past its peak, continued to inform the worldview of the era. Scholars were still engaged in astronomy, medicine, mathematics, and philosophy. The millennial celebrations would have provided fertile ground for re-examining these legacies, perhaps commissioning new works that synthesized past knowledge or offered new insights for the coming centuries. The astronomical calculations necessary to precisely mark the Islamic calendar, itself a testament to sophisticated scientific understanding, would have been a constant reminder of the intellectual heritage being celebrated.

While direct, widespread accounts of colossal, singular millennial festivals are scarce, the significance of 1000 AH cannot be understated. It was a period of profound cultural osmosis and intellectual continuity. The Islamic world in 1591/1592 CE was not a monolithic entity but a vibrant mosaic of cultures, languages, and interpretations of faith, all united by a shared calendar that marked a profound milestone. The turn of the millennium was not just a date on a calendar; it was an invitation to reflect on a thousand-year journey of faith, knowledge, and civilization, a journey that continued to shape the world in myriad ways.

The impact of reaching this millennial marker was not one of abrupt change but rather a subtle shift in collective consciousness. It reinforced a sense of shared identity and historical continuity among Muslims worldwide. It spurred a renewed engagement with sacred texts and scholarly traditions, often leading to the production of new theological commentaries, historical chronicles, and scientific treatises. This intellectual output, spurred by the occasion, contributed to the ongoing development of Islamic thought and culture, ensuring that the legacy of the past millennium would continue to inform the future.

In essence, the Islamic world’s millennium celebrations in 1000 AH were less about public spectacle and more about a deep, collective spiritual and intellectual journey. It was a moment to pause, reflect on the blessings of the past, and face the future with a blend of hope, reverence, and an enduring commitment to the principles that had guided them for a thousand years. The echoes of these reflections continue to resonate in the rich heritage of Islamic civilization today.