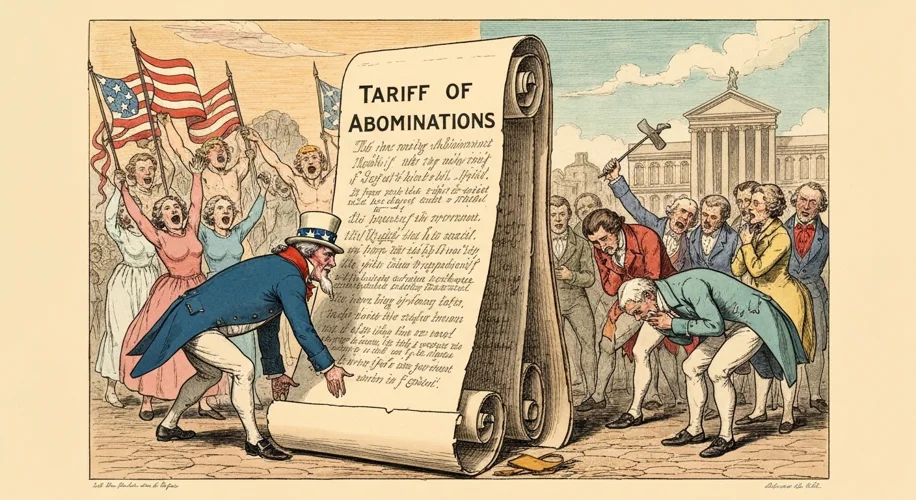

In the annals of American economic history, few pieces of legislation have stirred as much controversy and sectional discord as the Tariff of 1828. Dubbed the “Tariff of Abominations” by its detractors, this seemingly dry economic policy ignited a firestorm that threatened to tear the young nation asunder, offering a potent historical parallel to contemporary debates about trade and consumer costs.

A Nation Divided by Industry and Agriculture

The early 19th century United States was a land of stark contrasts. The North, increasingly industrialized, saw protective tariffs as a vital shield against cheaper foreign goods, fostering its burgeoning manufacturing sector. The South, however, remained resolutely agrarian, its economy deeply entwested with the export of cash crops like cotton, tobacco, and rice. For the South, tariffs were not a protective measure but a punitive tax. They drove up the cost of imported goods they relied upon and, critically, risked retaliatory tariffs from other nations on their agricultural exports.

The Road to Abomination

The seeds of the 1828 tariff were sown in earlier protectionist measures. However, the 1828 act represented a dramatic escalation. Its complex structure, riddled with duties on raw materials and manufactured goods alike, was a patchwork of compromises and political maneuvering. Northern industrialists lobbied fiercely for protection, while Southern representatives saw their economic future imperiled. The bill was crafted in such a way that it was almost guaranteed to pass, thanks to strategic alliances and a desire by some politicians to embarrass President John Quincy Adams and pave the way for Andrew Jackson’s ascent.

The tariff’s effects were immediate and severe. Prices for manufactured goods, from textiles to iron, surged. For the average Southerner, this meant a significant increase in their cost of living. A farmer needing a new plow or a merchant importing fine cloth found their expenses mounting, all while facing the specter of reduced export markets. It was perceived not as a policy for national prosperity, but as a naked grab for power and wealth by the industrial North at the expense of the agricultural South.

The Fury of Nullification

The backlash in the South was swift and passionate. Leading the charge was John C. Calhoun, Vice President under Adams and a towering intellectual figure of the South. Calhoun argued that the tariff was unconstitutional, violating the principles of states’ rights. He championed the doctrine of nullification, asserting that individual states had the right to declare federal laws unconstitutional and void within their borders.

The confrontation escalated dramatically in 1832 when South Carolina, echoing Calhoun’s arguments, passed an ordinance nullifying the federal tariff laws. The state declared that the tariffs were illegal and void, and that it would resist any attempt by the federal government to enforce them, even through military means. President Andrew Jackson, a staunch defender of federal authority, responded with equal ferocity. He issued a proclamation denouncing nullification as treasonous and threatened to use force to uphold the Union. The nation teetered on the brink of civil war.

A Compromise and Lasting Scars

Fortunately, cooler heads prevailed. A compromise, brokered by Henry Clay, was eventually reached. The Compromise Tariff of 1833 gradually reduced tariff rates over a decade, defusing the immediate crisis. South Carolina rescinded its nullification ordinance, and Jackson rescinded his proclamation. Yet, the “Tariff of Abominations” left indelible scars on the American psyche.

It starkly exposed the deep sectional divides that festered beneath the surface of national unity. The debate over states’ rights versus federal authority, inflamed by economic grievances, would continue to echo through the decades, ultimately contributing to the cataclysm of the Civil War.

For ordinary Americans, the “Tariff of Abominations” was more than just a collection of duties; it was a stark reminder of how economic policies, driven by powerful interests and political ambition, could directly impact their livelihoods, creating hardship and fostering a sense of injustice. It serves as a timeless lesson that the cost of protectionism, if not carefully managed, can be borne not just by foreign producers, but by the very citizens a government is sworn to protect.