In the digital age, where information flows like a ceaseless river, it’s easy to assume that the collection and utilization of data are entirely modern phenomena. Yet, the roots of this practice stretch back much further than the advent of the internet, intertwined with the very development of human knowledge and, ultimately, the rise of artificial intelligence.

Imagine scribes in ancient Mesopotamia, meticulously recording grain yields and trade transactions on clay tablets. Or consider the meticulous cataloging of the Great Library of Alexandria, a monumental effort to gather and preserve the world’s knowledge. These were not merely acts of record-keeping; they were early forms of data collection, driven by the fundamental human desire to understand, organize, and leverage information.

The Renaissance and the Enlightenment, periods of explosive intellectual growth, saw a burgeoning interest in empirical observation and systematic data gathering. Astronomers charted the stars with unprecedented precision, naturalists cataloged flora and fauna, and early statisticians began to quantify societal trends. These endeavors, though driven by scientific curiosity, laid the groundwork for understanding patterns and drawing conclusions from vast datasets – a precursor to the analytical engines of today.

As the Industrial Revolution swept across the globe, so too did the need for more efficient data management. The invention of the telegraph and the subsequent development of early computing machines, like Charles Babbage’s Analytical Engine in the 19th century, were attempts to automate and accelerate calculation and data processing. These were nascent steps, but they signaled a growing awareness of data’s potential power.

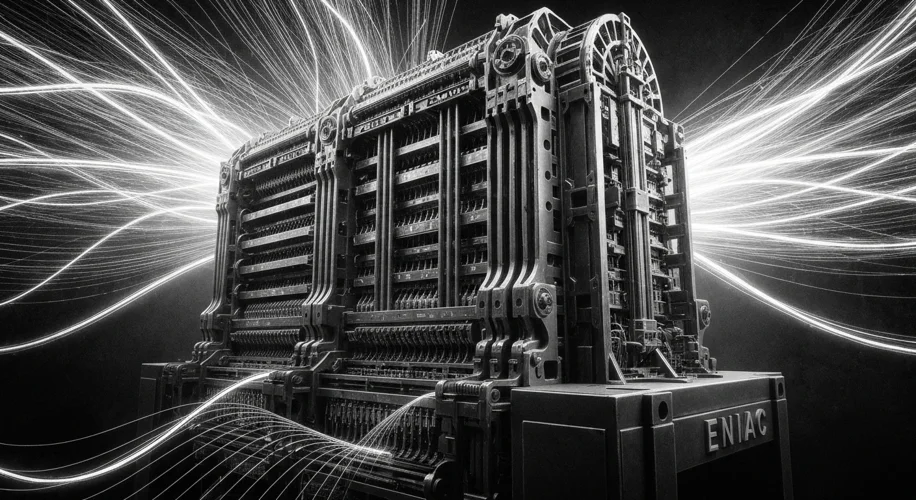

The 20th century witnessed a dramatic acceleration. World War II, in particular, spurred innovation in data analysis for code-breaking and military strategy. The ENIAC, one of the earliest electronic general-purpose computers, was a marvel of its time, capable of performing calculations at speeds previously unimaginable. It was a machine built to process data, to sift through complex problems, and to provide insights that could shape the course of history.

As computers became more powerful and accessible, the concept of ‘scraping’ – the automated extraction of data from various sources – began to take shape. In the early days of the internet, this often involved simple scripts designed to pull information from websites. Imagine early web developers creating simple programs to aggregate product prices from online stores or collect news headlines. These were rudimentary, often clumsy, but they represented a significant leap in the ability to gather information at scale.

However, this burgeoning power was not without its shadows. As data collection became more sophisticated, so did the ethical and legal questions. The very act of collecting and using information raised concerns about privacy, ownership, and potential misuse. Early debates, often unfolding in academic circles and legal journals, grappled with questions that resonate even today: Who owns the data? How should it be protected? What are the implications of using this information to influence or predict behavior?

Consider the burgeoning field of market research in the mid-20th century. Companies began to systematically collect consumer preferences and purchasing habits, using this data to tailor advertising and product development. While seemingly benign, this marked an early instance of large-scale data exploitation for commercial gain, raising questions about manipulation and informed consent.

The real explosion, of course, came with the internet and the subsequent rise of big data. Suddenly, the world was awash in digital information – every click, every search, every purchase left a trace. This provided an unprecedented feast for data collection and analysis.

This is where the story of data scraping truly converges with the development of artificial intelligence. AI, in its most fundamental sense, learns from data. The more data it has access to, the better it can identify patterns, make predictions, and perform tasks. Early AI research, often confined to laboratories, relied on carefully curated datasets. But as the internet opened up a universe of raw, unformatted information, data scraping became an indispensable tool for feeding these learning machines.

Algorithms were developed to