It begins with a cough, a sneeze, a fever. To us, it’s a nuisance, a few days in bed. But to the microscopic world, these are the sounds of an ancient battleground, a constant evolutionary arms race playing out in the wings of birds, and sometimes, alarmingly, in the lungs of humans.

Avian influenza, or bird flu, is not a new foe. Its history is etched in the annals of human and animal suffering, a silent threat that has, at various points, erupted into devastating pandemics. Understanding this history is not just an academic exercise; it’s a crucial step in preparing for the future.

The Whispers in the Flock: Early Observations and the Dawn of Understanding

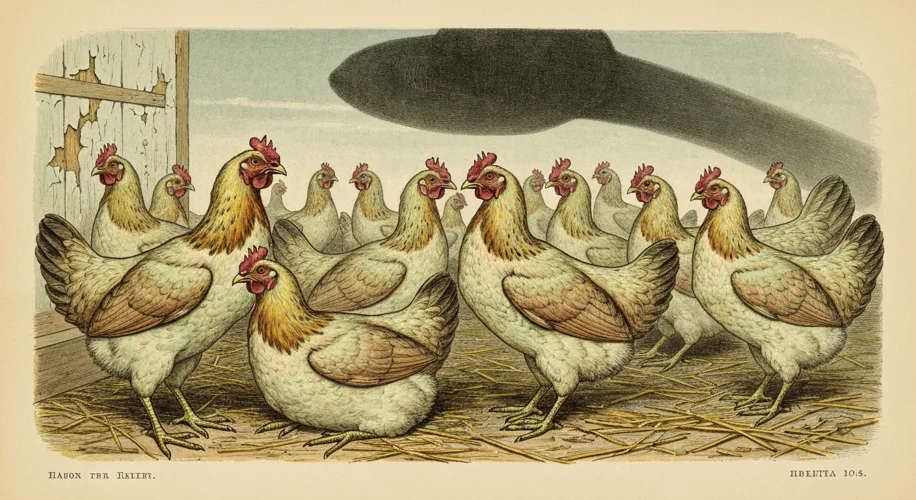

The exact origins of bird flu in humans are shrouded in the mists of time. However, hints of its existence can be found in historical veterinary records and agricultural accounts that described sudden, widespread deaths among poultry and wild birds. These events, often attributed to divine wrath or natural calamities, were the first subtle tremors of a force that would later demand global attention.

It wasn’t until the late 19th and early 20th centuries that science began to catch up. In 1878, the Italian veterinarian Ignazio Sanarelli described a highly contagious disease affecting chickens, later identified as avian influenza. But it was the influenza pandemic of 1918-1919, the infamous Spanish Flu, that truly revealed the terrifying potential of these avian viruses to jump species. While the exact strain responsible for the Spanish Flu is still debated, strong evidence points to an avian origin, likely a highly pathogenic H1N1 virus. This pandemic, which claimed an estimated 50 to 100 million lives worldwide, was a stark, brutal lesson in the power of zoonotic diseases – diseases that spill over from animals to humans.

The Shifting Strains: From Poultry Farms to Global Alerts

Throughout the 20th century, various strains of avian influenza continued to circulate among bird populations. Most of these were low pathogenic (LPAI) strains, causing mild illness. However, the capacity for these viruses to mutate and occasionally gain high pathogenicity (HPAI) remained a persistent concern. These shifts were particularly evident in the poultry industry, where intensive farming practices created ideal conditions for rapid transmission and evolution. Outbreaks in farmed birds could lead to significant economic losses and, crucially, increased opportunities for human exposure.

The first major human pandemic of the 20th century attributed to avian influenza occurred in 1957 with the H2N2 pandemic, known as the Asian Flu. This virus, too, is believed to have originated in birds. It swept across the globe, causing an estimated 1 to 4 million deaths. Just over a decade later, in 1968, the H3N2 virus, the Hong Kong Flu, emerged, again with avian origins, claiming another 1 to 4 million lives. These pandemics, while devastating, were generally less lethal than the 1918 Spanish Flu, but they underscored a disturbing pattern: avian influenza viruses were a recurring, significant threat to global public health.

The Modern Era: H5N1 and the Fear of the Next Big One

The late 20th and early 21st centuries brought a new level of vigilance and a specific focus on the H5N1 strain. First identified in 1996 in China, H5N1 proved to be exceptionally virulent in birds, causing massive die-offs in poultry and wild birds. While human infections were initially rare, they were often severe, with high fatality rates, primarily occurring in individuals with close contact with infected birds. The years between 2003 and 2006 saw significant H5N1 outbreaks in Asia, sparking global alarm. The scientific community worried that H5N1, with its high mortality, could mutate to become easily transmissible between humans, potentially triggering a pandemic even more catastrophic than its predecessors.

This fear spurred unprecedented international collaboration. The World Health Organization (WHO) and national health agencies ramped up surveillance systems, developed pandemic preparedness plans, and invested heavily in vaccine research and antiviral stockpiles. The focus shifted to preventing the virus from gaining a foothold in human populations and, failing that, containing its spread should human-to-human transmission become efficient.

Beyond H5N1: The Ever-Evolving Threat

While H5N1 captured headlines, other avian influenza strains continued to pose risks. The H7N9 strain, for instance, emerged in China in 2013, causing severe illness in humans with a significant mortality rate, though its ability to spread efficiently between people remained limited. Each new outbreak, whether H5N1, H7N9, or other subtypes, served as a potent reminder that the threat from avian influenza was dynamic and adaptable.

Scientists continue to monitor wild bird populations, domestic poultry, and human cases globally. They analyze the genetic makeup of circulating viruses, looking for changes that could signal an increased risk of human transmission or enhanced virulence. This continuous surveillance is the front line of defense against the next potential pandemic. The scientific community also grapples with the complex ecological factors that drive these spillover events, including climate change, global trade, and changes in land use that bring humans and animals into closer, often more stressful, contact.

Lessons from the Past, Preparedness for the Future

The history of bird flu outbreaks is a sobering narrative of nature’s relentless evolutionary power and humanity’s ongoing struggle to adapt. From the subtle deaths in ancient poultry flocks to the sophisticated global surveillance networks of today, the threat has evolved, as have our responses. The Spanish Flu, Asian Flu, and Hong Kong Flu pandemics demonstrated the devastating potential of avian viruses. The more recent scares with H5N1 and H7N9 highlighted the ever-present danger of highly pathogenic strains and underscored the critical need for robust public health infrastructure, rapid vaccine development, and international cooperation.

As we stand in 2025, the shadow of avian influenza looms large. While no human pandemic has yet erupted from the H5N1 strain as feared, the virus continues to circulate and evolve. The lessons learned from past outbreaks – the importance of surveillance, rapid response, and understanding the human-animal interface – are more vital than ever. The history of bird flu is not just a story of past tragedies; it is a vital guide for navigating the ongoing challenge of living with nature’s most potent and unpredictable threats.