In the grand tapestry of human history, threads of injustice and suffering have been woven alongside vibrant hues of progress and enlightenment. For millennia, humanity has grappled with the fundamental question of how individuals should be treated, not just by their rulers, but by each other. While the concept of inherent rights may seem modern, its roots stretch back to the dawn of civilization.

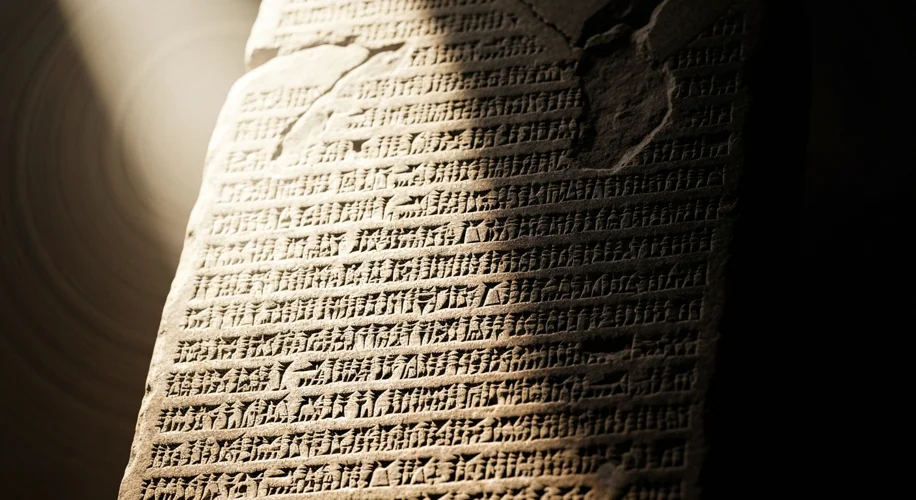

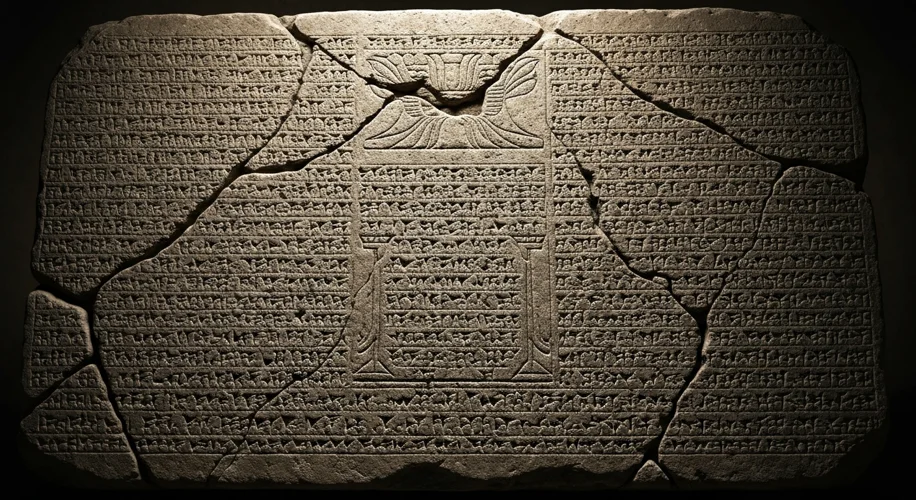

Imagine the earliest human communities. Even in these nascent societies, there were likely unspoken rules, understandings about fairness, and prohibitions against wanton cruelty. These weren’t written down in grand declarations, but they formed the bedrock of social cohesion. As civilizations grew, so did the attempts to codify these ideas. The Code of Hammurabi, dating back to ancient Babylon around 1754 BCE, is a prime example. While it famously espoused “an eye for an eye,” it also laid down laws for commerce, property, and family, suggesting a societal concern for order and, to some extent, justice.

Further east, in ancient India, the concept of Dharma emphasized duty, righteousness, and a cosmic order that implied a certain respect for all beings. Philosophers and religious leaders pondered the nature of a just society and the moral obligations of individuals and rulers. Similarly, in ancient Greece, thinkers like Aristotle explored the idea of natural justice, suggesting that some principles of fairness were not merely societal constructs but were inherent in the natural world.

Fast forward to the Enlightenment, a period of profound intellectual ferment in Europe. Philosophers like John Locke articulated the concept of natural rights – life, liberty, and property – arguing that these were not granted by governments but were inherent to all humans. These ideas were revolutionary, challenging the divine right of kings and sowing the seeds for democratic revolutions. The American Declaration of Independence in 1776, with its immortal phrase “all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness,” was a direct descendant of these Enlightenment ideals.

Yet, the path to universal recognition of these rights was fraught with peril and punctuated by unimaginable horrors. The 20th century, despite its technological marvels, witnessed unprecedented brutality. The systematic persecution and extermination of millions during the Holocaust by Nazi Germany exposed the terrifying depths to which humanity could sink when basic human dignity was disregarded on a state-sponsored scale. The sheer scale and systematic nature of the atrocities, the chilling efficiency with which human beings were stripped of their rights, their lives, and their very humanity, shocked the conscience of the world.

In the ashes of World War II, a desperate need for a global framework to prevent such atrocities from ever happening again took hold. Leaders from around the world recognized that peace and security could not be achieved if fundamental human rights were not universally protected. This urgent imperative led to the creation of the United Nations in 1945. But the UN’s work was far from over. A crucial step was needed to define what these fundamental human rights actually were.

This monumental task fell to the newly formed United Nations Commission on Human Rights, chaired by Eleanor Roosevelt, the formidable former First Lady of the United States. For years, delegates from diverse cultural, political, and philosophical backgrounds wrestled with the precise wording, seeking common ground on principles that could resonate globally. They debated civil and political rights, such as freedom of speech and assembly, alongside economic, social, and cultural rights, like the right to work and education.

The result of this arduous process was the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), adopted by the UN General Assembly on December 10, 1948. This document, a landmark achievement, was not a legally binding treaty at the time, but a common standard of achievement for all peoples and all nations. It proclaimed that “all human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights” and laid out 30 articles covering a broad spectrum of rights, from the prohibition of torture to the freedom of thought and religion.

The UDHR was a radical departure. It asserted that rights are not granted by states but belong to individuals by virtue of their humanity. It was a powerful moral compass, guiding subsequent international law and inspiring countless national constitutions and human rights movements worldwide. It provided a common language for discussing human dignity and a benchmark against which the actions of governments could be measured.

However, the journey did not end with the UDHR. It was a beginning, a foundation upon which a more robust international human rights legal framework would be built. Over the following decades, this led to legally binding treaties, such as the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, which, along with the UDHR, form the International Bill of Human Rights. Further treaties addressed specific issues like the prevention of genocide, the rights of women, the rights of the child, and the prohibition of torture.

Today, in 2025, the struggle for human rights continues. While the UDHR and subsequent legal instruments have undoubtedly advanced global norms, their full implementation remains a challenge. Violations persist in many parts of the world, and the interpretation and application of these rights are subjects of ongoing debate. Yet, the legacy of these declarations is undeniable. They represent a profound evolution in human thought, a testament to our capacity for empathy and our persistent aspiration for a world where every individual can live with dignity, freedom, and justice. The echoes of those ancient oaths and the bold pronouncements of the UDHR continue to inspire the fight for a more humane future.