The very earth beneath Colombia has long held a secret, a dark, viscous treasure that has shaped its destiny, fueled its economy, and ignited its conflicts. This is the story of oil and gas in Colombia, a narrative as rich and complex as the hydrocarbons themselves, stretching back over a century.

Long before the roar of modern industry, indigenous communities in Colombia held a reverence for the “sacred fire” seeping from the ground. But it wasn’t until the dawn of the 20th century that this natural phenomenon would be recognized for its immense potential. The quest for this black gold began in earnest with foreign investment, a familiar dance in Latin American resource extraction. Companies like Tropical Oil Company, a subsidiary of Standard Oil, arrived with dreams of immense wealth, eyes fixed on the promising geological formations of the Magdalena Medio region.

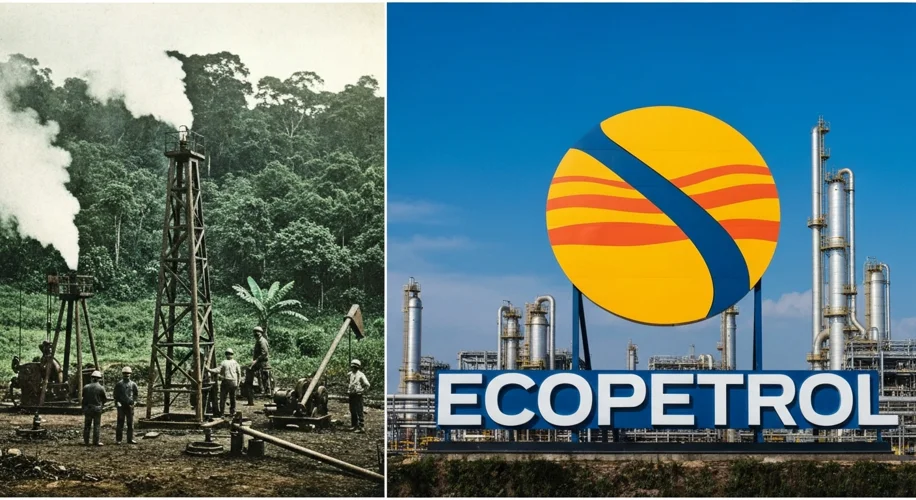

Imagine the scene: in the early 1900s, hardy explorers, armed with rudimentary equipment and unwavering determination, ventured into the dense Colombian jungle. Mosquitoes buzzed incessantly, the humidity was a suffocating blanket, and the threat of disease was ever-present. Yet, they pressed on, driven by the promise of striking black gold. In 1918, their persistence paid off with the discovery of the La Cira well, a gusher that marked the beginning of Colombia’s true oil age.

The impact was immediate. La Cira became a symbol of progress, drawing more investment and ushering in an era of rapid expansion. The infrastructure required to extract and transport this precious commodity began to snake across the landscape: pipelines, roads, and burgeoning towns. Barrancabermeja, a small riverside settlement, transformed into a bustling oil city, its identity inextricably linked to the black tide flowing beneath its streets.

However, this era of burgeoning prosperity was not without its shadows. The early days were marked by precarious labor conditions and a stark imbalance of power between foreign companies and the Colombian people. The Barrancabermeja massacre of 1927 stands as a grim testament to this tension. Workers demanding better wages and conditions clashed with company security and government forces, resulting in a tragic loss of life. This event sowed the seeds of discontent and fueled a growing sense of nationalistic fervor regarding the control of its own resources.

As the decades turned, so did the ownership of Colombia’s oil. In 1951, a pivotal moment arrived when the Colombian state, through the newly formed Empresa Colombiana de Petróleos (Ecopetrol), took control of the oil fields previously operated by Tropical Oil Company. This nationalization was a triumphant assertion of sovereignty, a declaration that Colombia intended to chart its own course with its most valuable resource.

Ecopetrol’s rise coincided with significant discoveries, such as the Caño Limón oil field in the 1980s, which revitalized the nation’s production and export capacity. Yet, this newfound wealth often became a double-edged sword. The lucrative nature of oil exports made Colombia a target for illicit actors and fueled the protracted internal armed conflict that has plagued the nation for decades. Rebel groups, like the ELN (National Liberation Army), frequently targeted oil infrastructure, disrupting production, extorting companies, and using the proceeds to finance their insurgency. The ubiquitous pipelines became arteries of both commerce and conflict, vulnerable to sabotage and attack.

Consider the year 1998. A devastating attack on the Caño Limón pipeline, attributed to the ELN, unleashed millions of gallons of crude oil into the pristine Cúcuta River. The environmental catastrophe was immense, decimating ecosystems and impacting the lives of local communities for years to come. These acts of violence, coupled with the constant threat of kidnapping and extortion, made operating in the oil sector a perilous endeavor, often forcing international companies to weigh profit against the safety of their personnel.

Beyond the immediate violence, the oil industry has also been a focal point for environmental debates. The extraction and processing of oil carry inherent risks, from land degradation and water contamination to greenhouse gas emissions. As global awareness of climate change has grown, so too has the scrutiny of Colombia’s reliance on fossil fuels. Activist groups have consistently raised concerns, demanding greater environmental protections and advocating for a transition to renewable energy sources.

The economic impact of oil and gas on Colombia cannot be overstated. For decades, hydrocarbon exports have been a dominant force in the nation’s trade balance, generating significant revenue that has funded public services and infrastructure projects. However, this heavy reliance has also exposed the economy to the volatile fluctuations of global oil prices. When prices soar, Colombia thrives; when they plummet, the nation faces economic strain, underscoring the need for diversification.

Today, as the world grapples with energy transitions, Colombia stands at a critical juncture. The legacy of its black gold is undeniable – a history etched in industrial progress, armed struggle, and environmental challenges. The future of its oil and gas sector, and indeed its economy, hinges on navigating this complex inheritance, balancing the need for energy security with the imperative of environmental stewardship and social equity. The earth beneath Colombia still holds its secrets, but the story of its oil and gas is far from over; it is a continuing saga of ambition, conflict, and the enduring quest for a sustainable future.

Key Takeaways:

- Early Discoveries: Oil exploration in Colombia began in the early 20th century, with significant discoveries like the La Cira well in 1918.

- Nationalization: The Colombian state, through Ecopetrol, took control of oil assets in 1951, marking a pivotal moment for national sovereignty.

- Conflict and Sabotage: Oil infrastructure has frequently been targeted by guerrilla groups, leading to environmental damage and economic disruption.

- Economic Reliance: Oil exports have been a major driver of Colombia’s economy, but also subject to global price volatility.

- Environmental Concerns: The industry faces ongoing scrutiny regarding its environmental impact and the need for sustainable practices.