Imagine a horizon, not dotted with the sails you know, but dominated by colossal vessels, their hulls painted in vibrant hues, their masts adorned with banners that ripple like dragon scales in the wind. This wasn’t a scene from a fantastical tale, but the breathtaking reality of the Ming Dynasty’s greatest maritime expeditions, led by the indomitable Admiral Zheng He.

In the early 15th century, as Europe was still grappling with the aftermath of the Black Death and the Hundred Years’ War, China was entering a golden age of exploration. The Yongle Emperor, who had seized the throne in a bloody civil war, desired to project the might and splendor of his empire across the known world. To achieve this, he turned to a eunuch admiral named Zheng He, a man of immense talent and experience, who commanded a fleet of unprecedented scale.

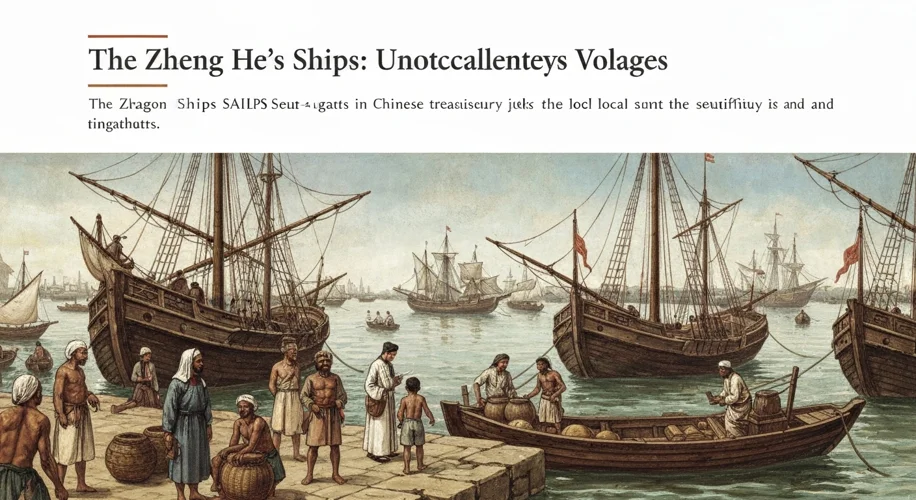

The first voyage set sail in 1405 from Nanjing, a city that then pulsed with the energy of a global power. Zheng He’s fleet was not a collection of mere ships; it was a floating city. Estimates suggest the largest ships, known as ‘Treasure Ships’ or ‘Baochuan’, could be over 400 feet long – behemoths that dwart any European vessel of the time, including Columbus’s Santa Maria. Some accounts speak of them having nine masts and carrying hundreds of crew members, soldiers, and scholars. In total, Zheng He commanded fleets that numbered in the hundreds, carrying tens of thousands of men.

For nearly three decades, from 1405 to 1433, Zheng He embarked on seven major expeditions. His voyages crisscrossed the Indian Ocean, reaching as far as the east coast of Africa. They sailed to Southeast Asia, calling at ports in Champa (modern Vietnam), Siam (Thailand), Malacca, and Java. They journeyed to India, visiting Calicut and Ceylon (Sri Lanka), and then westward to Hormuz on the Persian Gulf. The final voyages even took them to the coast of East Africa, visiting Mogadishu, Mombasa, and Malindi.

These were not conquest voyages. Zheng He’s missions were primarily diplomatic and economic. His fleet carried lavish gifts – silks, porcelain, lacquerware, and precious metals – to present to foreign rulers. In return, they sought exotic goods: spices, gems, medicinal herbs, ivory, and even giraffes, which were a source of great wonder in the Chinese court. The ‘treasure’ in ‘treasure fleet’ referred not just to the goods traded, but to the immense wealth and prestige China was showcasing.

Zheng He himself was a fascinating figure. Born Ma He into a Muslim family in Yunnan province, he was captured during a Ming campaign and castrated, becoming a eunuch in the imperial court. His loyalty and skill, however, earned him the trust of the Yongle Emperor, who granted him the surname ‘Zheng’. He was a devout Muslim, and the voyages were notable for their religious tolerance, with mosques being built in foreign lands and prayers offered for the Emperor’s long life.

The scale of Zheng He’s expeditions was staggering. Consider the logistics: provisioning thousands of men and animals for journeys that could last for years, navigating vast oceans using sophisticated charts and astronomical knowledge, and maintaining discipline and order across such a massive force. It was a feat of organization and engineering that remains awe-inspiring.

However, the era of the great treasure fleets was remarkably short-lived. After Zheng He’s final voyage in 1433, the expeditions ceased. The reasons are complex and debated by historians. Political shifts within the Ming court, the rise of conservative Confucian officials who viewed maritime trade as a distraction from internal matters and a threat to traditional agrarian values, and the enormous cost of these voyages all played a role. China turned inward, its vast navy was dismantled, and its seafaring ambitions were largely abandoned for centuries.

The legacy of Zheng He is one of missed opportunities for the rest of the world. While European explorers like Columbus were just beginning their journeys, China had already demonstrated an unparalleled capacity for long-distance maritime exploration. Had these voyages continued, the history of global trade, colonialism, and cultural exchange might have unfolded very differently. Zheng He’s voyages stand as a testament to China’s past maritime prowess, a spectacular chapter in history that continues to capture the imagination, reminding us that the age of exploration was not solely a European endeavor.