The year is 1488. The air in Lisbon crackles with anticipation, thick with the scent of salt and foreign spices. Bartholomew Diaz, a name soon to be etched in the annals of history, stands on the docks, gazing south. His mission: to round the treacherous southern tip of Africa, a feat whispered about in hushed tones, a barrier that had stymied explorers for centuries.

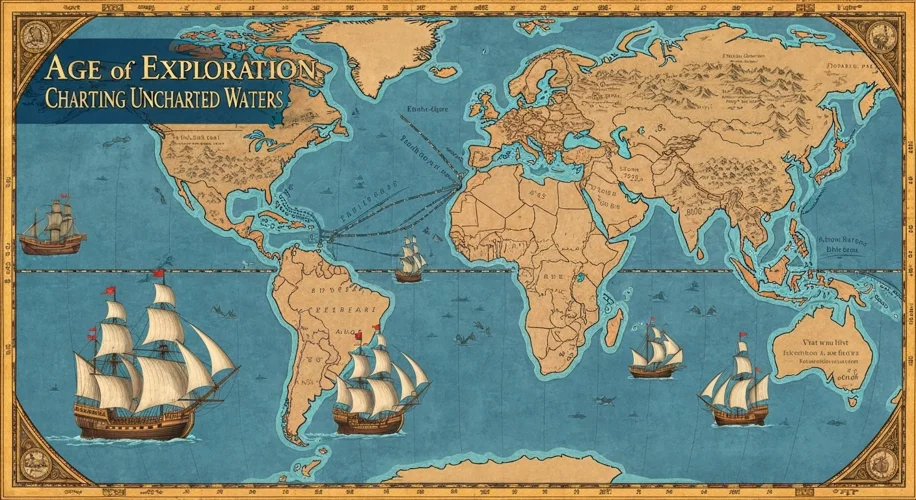

This was the dawn of a new era, an epoch where the familiar horizons of Europe began to recede, replaced by the tantalizing promise of the unknown. The Age of Exploration, stretching roughly from the early 15th to the early 17th century, was not merely a series of voyages; it was a seismic shift in human consciousness, a bold gamble fueled by a potent cocktail of curiosity, commerce, and conquest.

For centuries, the world beyond Europe was shrouded in myth and speculation. The Silk Road, that legendary artery of trade, connected East and West, but the journey was perilous and the goods exorbitantly priced. The desire for direct access to the riches of the East – silks, spices, precious metals – burned brightly in the hearts of European monarchs and merchants. The Ottoman Empire’s control over traditional routes only intensified this yearning, creating a powerful economic and political impetus to find new paths.

But it wasn’t just about gold and silks. The Renaissance had reawakened a spirit of inquiry, a fascination with the classical world and a burgeoning belief in human potential. Cartography, shipbuilding, and navigational tools like the astrolabe and magnetic compass were advancing, making longer, more ambitious voyages feasible. The Portuguese, under the visionary patronage of Prince Henry the Navigator, were pioneers, meticulously charting the coast of Africa, establishing trading posts, and pushing the boundaries of the known world.

Diaz’s successful rounding of the Cape of Good Hope in 1488 was a monumental achievement, a testament to European seafaring prowess and an opening gambit in the grand game of global exploration. It proved that the ocean route to Asia was not an impossibility, but a tangible reality waiting to be navigated. The world, it seemed, was much larger and far more interconnected than anyone had imagined.

Then came Christopher Columbus. In 1492, sailing under the Spanish flag, he embarked on a westward voyage, seeking a shortcut to the Indies. His landfall in the Caribbean, though mistaken for Asia, would irrevocably alter the course of history. It wasn’t just a discovery of new lands; it was the violent collision of worlds.

The consequences were profound and multifaceted. The Columbian Exchange, a massive transfer of plants, animals, culture, human populations, technology, diseases, and ideas between the Americas, West Africa, and the Old World, began. European diseases, to which indigenous populations had no immunity, wreaked havoc, leading to catastrophic population decline. Conversely, crops like potatoes and maize from the Americas would revolutionize European agriculture and diets.

This era also marked the brutal inception of colonialism. European powers, driven by mercantilism and the pursuit of empire, established colonies, exploited resources, and subjugated indigenous peoples. The transatlantic slave trade, a horrific chapter in human history, saw millions of Africans forcibly transported to the Americas to labor on plantations, forever altering the demographic and social landscapes of continents.

Explorers like Ferdinand Magellan would circumnavigate the globe, proving definitively that the Earth was round. Vasco da Gama found the sea route to India, opening up direct trade that bypassed intermediaries. John Cabot charted the North American coast for England, and Jacques Cartier claimed lands for France. Each voyage added a piece to the global puzzle, expanding maps and, for better or worse, weaving disparate cultures into a single, complex tapestry.

The Age of Exploration was a period of immense courage and daring, but also of profound ethical compromise. It unleashed forces that reshaped global power structures, economies, and societies. It spurred scientific advancement and intellectual curiosity, yet it also laid the foundation for centuries of exploitation and inequality. Understanding this era means grappling with its dual legacy: the expansion of human knowledge and connection, intertwined with the grim realities of conquest and subjugation.

As we look back from our vantage point in 2025, the echoes of these voyages still resonate. The world we inhabit today, with its interconnected economies, diverse populations, and complex geopolitical relationships, is a direct product of those ambitious, and often brutal, expeditions that began centuries ago, when brave souls first dared to sail beyond the edge of the known world. The quest for what lay beyond the horizon continues, a perpetual human drive that, for better or worse, has always propelled us forward.