Imagine a world untouched by human hands, a paradise teeming with life found nowhere else. Now, picture that world irrevocably altered by the arrival of strangers, bringing with them not just new tools and ideas, but also unintended consequences that would lead to the swift and silent disappearance of a unique creature. This is the tragic story of the Dodo, a bird whose very name has become synonymous with extinction.

For centuries, the Dodo (Raphus cucullatus) lived a life of serene isolation on the island of Mauritius, a volcanic gem in the Indian Ocean. This wasn’t just any island; it was a living laboratory of evolution, where species developed in the absence of terrestrial predators. The Dodo was a prime example of this evolutionary experiment. Flightless and unafraid, it waddled through the island’s lush forests, its existence shaped by a gentle environment that offered both sustenance and sanctuary.

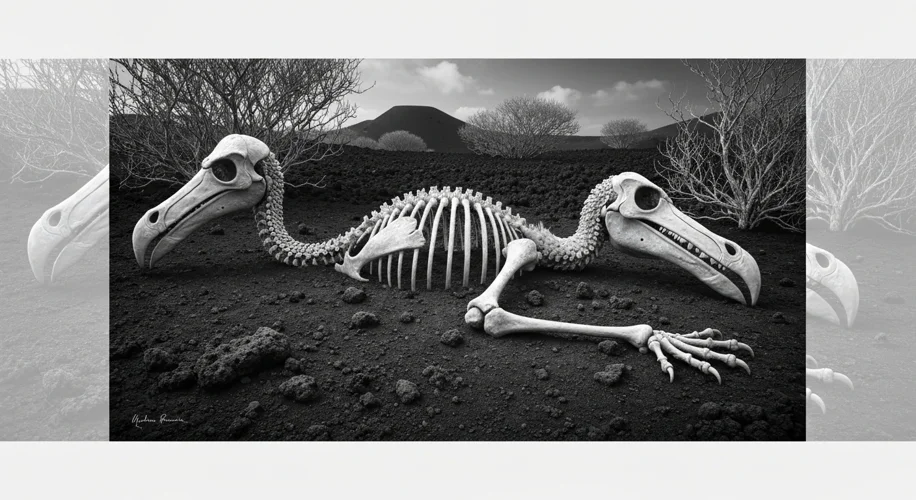

These birds were large, perhaps reaching a meter in height, with plump bodies, stout legs, and a distinctive hooked beak. They were ground-dwellers, nesting on the ground and feeding on fruits and seeds. Without natural predators, they had no need for the complex evasive maneuvers that birds elsewhere developed. Their lack of fear wasn’t foolishness; it was a perfect adaptation to their perfect world.

Then, in the late 16th century, the world changed. Dutch sailors, arriving in 1598, were the first significant human visitors to Mauritius. They found the dodo a curious sight – a large, flightless bird, seemingly tame and easy to catch. The early accounts, though sometimes embellished, paint a picture of a creature that regarded humans with little more than mild curiosity. For the sailors, the dodo was a convenient source of fresh meat, a welcome respite on their long voyages.

But the sailors were just the vanguard. Their arrival marked the beginning of a devastating chain of events. Soon, Mauritius became a stopover point for ships engaged in trade and exploration, bringing not only humans but also the animals that accompanied them: rats, pigs, monkeys, and cats. These introduced species were the dodo’s undoing. They invaded the dodo’s ground nests, devouring eggs and young birds. The dodo, unequipped by nature to defend its young from such novel threats, was helpless.

The habitat itself also began to suffer. Forests were cleared for settlements and agriculture, diminishing the dodo’s food sources and nesting grounds. While hunting by humans contributed to the decline, the true culprits were the invasive species and habitat destruction, unleashed by human presence.

The dodo’s extinction was not a single, dramatic event, but a gradual fading. By the mid-17th century, sightings became increasingly rare. The last confirmed sighting is believed to have occurred around 1662, though some unconfirmed reports persisted for a few more decades. The bird that once ambled freely through its island home had vanished, leaving behind only sketches, fragmented bones, and a stark lesson.

The dodo’s story is a microcosm of a larger, ongoing tragedy: the vulnerability of island endemics. Islands, by their nature, foster unique evolutionary paths. Species that evolve in isolation often lack the defenses against new diseases, predators, and competitors that arrive with human activity. The dodo became an icon for this vulnerability, a symbol of how quickly an entire species can be erased from existence.

Today, the dodo remains etched in our collective consciousness, not just as a lost species, but as a potent reminder of humanity’s impact on the natural world. Its story compels us to consider the delicate balance of ecosystems and the profound responsibility we bear as stewards of the planet. The dodo’s silence serves as a perpetual echo, urging us to protect the unique biodiversity that still graces our world, before other species join its legendary, albeit tragic, ranks.