The emerald islands of Hawaiʻi, a necklace of volcanic jewels strung across the vast Pacific, are more than just a tropical paradise. For centuries, they were a living testament to a profound and intricate relationship between people and nature, a relationship nurtured by the traditional practices and deep knowledge systems of Native Hawaiians. This wasn’t a relationship of dominion, but one of reciprocity, where humans understood themselves as integral threads in the vibrant tapestry of the ʻāina (land).

Imagine a time before steel plows and chemical fertilizers. The ancestral Hawaiians, arriving from distant Polynesian shores around 1,500 years ago, found islands rich in biodiversity but also acutely vulnerable. Their survival, and the flourishing of their culture, depended on their ability to not just subsist, but to thrive in harmony with their surroundings. This led to the development of sophisticated land and resource management systems, known collectively as mālama ʻāina – the act of caring for the land.

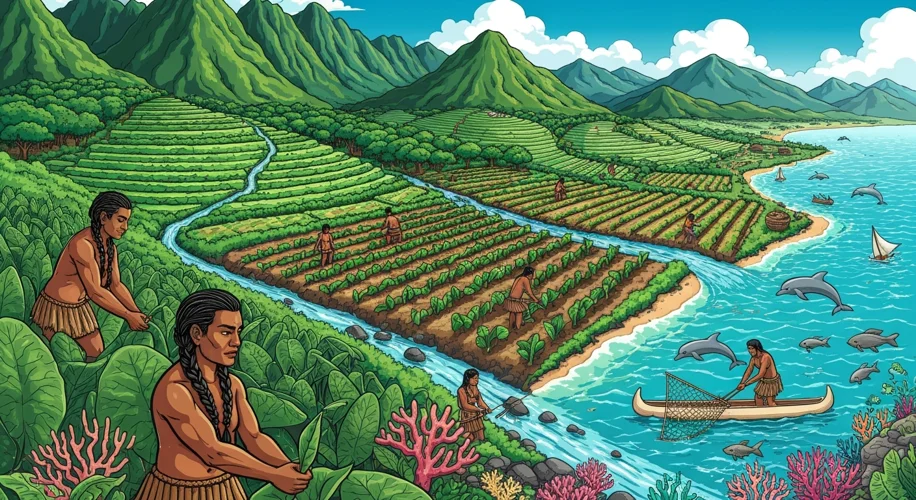

At the heart of mālama ʻāina was the concept of ahupuaʻa. These were large, wedge-shaped land divisions that typically extended from the mountains (mauka) down to the sea (makai). This ingenious design ensured that each community had access to a diverse range of resources: freshwater streams and forests in the uplands, fertile agricultural land in the mid-slopes, and rich fishing grounds along the coast. It was a natural, self-sustaining ecosystem, managed with a keen understanding of ecological flows.

Within the ahupuaʻa, a complex system of resource management was in place. For agriculture, the Hawaiians developed intricate irrigation systems and terraced loʻi kalo (taro patches). Taro, a staple crop, required meticulous attention, and the cultivation methods ensured that the soil remained fertile and the water resources were used efficiently. Certain areas were designated for specific crops, and crop rotation was practiced to maintain soil health.

Forests were not merely sources of timber; they were considered sacred, the home of the gods and the origin of fresh water. Specific trees were harvested sustainably, often with rituals and prayers, ensuring that the forest could regenerate. For example, the valuable koa tree, used for canoes and sacred objects, was harvested with great care, and efforts were made to replant or encourage new growth. The undergrowth was managed through controlled burning, a practice that cleared land for cultivation and also stimulated the growth of edible plants and grasses.

The ocean, a vital source of sustenance, was also managed with great wisdom. Fish populations were protected through the establishment of kapu (sacred prohibitions) on certain fishing grounds during breeding seasons. These kapu were strictly enforced, and their violation carried severe penalties. Different fishing techniques were employed for different species and seasons, preventing overfishing and ensuring a continuous supply of seafood. Marine areas were often carefully tended, with coral reefs sometimes being managed to enhance fish habitats.

This profound respect for nature was deeply embedded in Hawaiian cosmology and spirituality. The concept of mana – spiritual power or energy – was believed to reside in all living things, from the smallest insect to the grandest mountain. To harm the environment was to insult the gods and to diminish one’s own mana. This worldview fostered a sense of responsibility and interconnectedness, where every action had a ripple effect on the natural world and the community.

The consequences of this stewardship were profound. For centuries, the Hawaiian Islands supported a thriving population, living in balance with their environment. Their agricultural systems were highly productive, and their resource management practices ensured the long-term health of the ecosystems. However, the arrival of Westerners in the late 18th century marked a catastrophic turning point. The introduction of new diseases, coupled with a foreign mindset focused on exploitation and private ownership of land, led to the rapid decline of the Native Hawaiian population and the disruption of traditional practices.

Today, as Hawaiʻi grapples with the challenges of over-tourism, invasive species, and the impacts of climate change, the wisdom of mālama ʻāina is more relevant than ever. Modern efforts to revive traditional ecological knowledge and stewardship practices offer a path forward. From community-led reforestation projects to sustainable aquaculture initiatives, Native Hawaiians and their allies are working to heal the land and reconnect with the ancestral wisdom that once sustained these islands. The legacy of mālama ʻāina is not just a historical footnote; it is a vital blueprint for a sustainable future, a powerful reminder that true prosperity lies not in conquering nature, but in living as its humble, respectful guardians.