Imagine a world without potatoes. No crispy fries, no creamy mash, no comforting baked potatoes. It’s a culinary landscape almost unrecognizable. Yet, for millennia, this starchy marvel remained hidden away in the rugged peaks of the Andes Mountains, an exclusive treasure for the peoples who cultivated it. Its journey from a wild, unassuming plant to a global food staple is a saga of human ingenuity, cultural exchange, and a testament to nature’s quiet power.

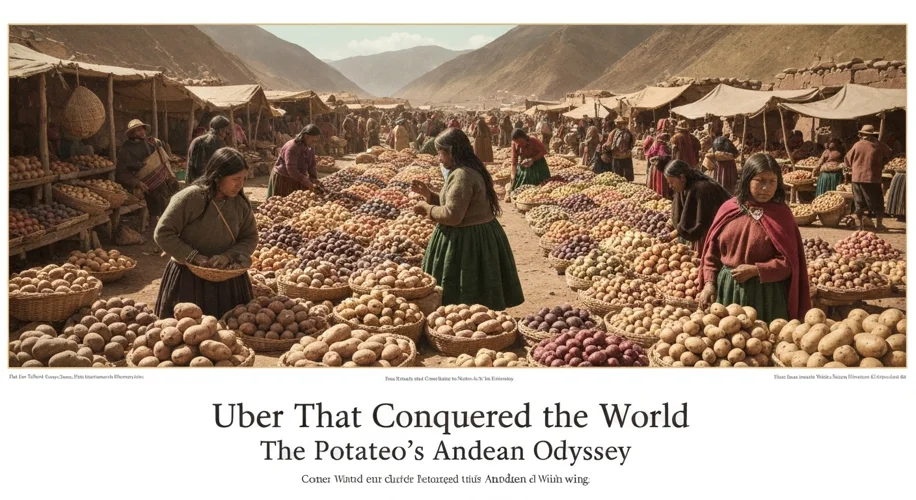

Our story begins not in the bustling markets of Europe, but amidst the breathtaking, often unforgiving, altitudes of the Andean Altiplano, a vast, high-altitude plateau in South America. Here, thousands of years ago, indigenous peoples like the ancestors of the Inca began to domesticate a wild relative of the potato, a plant that bore little resemblance to the uniform tubers we know today. These early potatoes were small, often bitter, and grew in a staggering diversity of shapes, colors, and textures.

These Andean civilizations, particularly the Inca, were master cultivators. Facing a challenging environment, they developed sophisticated agricultural techniques, including terracing the steep hillsides and creating complex irrigation systems. The potato wasn’t just food; it was a cornerstone of their society. It provided sustenance in a region where maize (corn) struggled to grow, offering a reliable and nutritious food source that allowed their populations to thrive. They developed methods to preserve potatoes, most notably by creating chuño, a freeze-dried product that could be stored for years, providing a vital buffer against famine. The sheer variety they cultivated speaks volumes about their understanding of this plant; over 4,000 varieties are believed to have existed.

Then came the seismic shift of the 16th century – the arrival of the Spanish conquistadors. Drawn by tales of gold and silver, they stumbled upon a different kind of treasure. While initially dismissive of the humble potato, often viewing it as food for livestock or the lower classes, the Spanish eventually brought it back to Europe. This transatlantic voyage, however, was not an immediate success story for the potato.

In Europe, the potato was met with suspicion and fear. Its origins in the New World, its subterranean growth (associated with the devil by some), and its resemblance to poisonous nightshade plants led to widespread mistrust. It was blamed for diseases like leprosy and was even thought to cause madness. For decades, it remained a curiosity, a botanical oddity grown in aristocratic gardens, or a crop for the desperate and the poor. The Irish, however, were among the first to truly embrace the potato. Its high yield, nutritional value, and ability to grow in poor soil made it an ideal crop for a population often living at the margins.

The reliance on the potato, particularly in Ireland, would have devastating consequences. In the mid-19th century, a blight known as Phytophthora infestans swept across Europe, decimating potato crops. Ireland, having become overwhelmingly dependent on a single variety of potato – the Lumper – for its sustenance, was hit with catastrophic force. The Great Famine, which lasted from 1845 to 1852, saw over a million people die and another million emigrate, forever altering the course of Irish history and its relationship with Britain.

Despite this tragic chapter, the potato’s resilience and nutritional power eventually won over the world. Its ability to produce more food per acre than most other crops made it a vital tool in combating hunger as European populations continued to grow. From Ireland to Russia, from India to China, the potato became a dietary staple, fueling industrial revolutions and supporting burgeoning cities. Its versatility in cooking and its adaptability to various climates further cemented its global status.

The potato’s journey is a remarkable example of how a seemingly simple plant can shape civilizations. It transformed diets, fueled population growth, and even contributed to immense tragedy. It reminds us that history is not just made by kings and conquerors, but by the quiet, persistent efforts of farmers and the enduring power of the earth’s bounty. The next time you enjoy a simple potato dish, remember the incredible odyssey of this Andean treasure, a tuber that truly conquered the world.