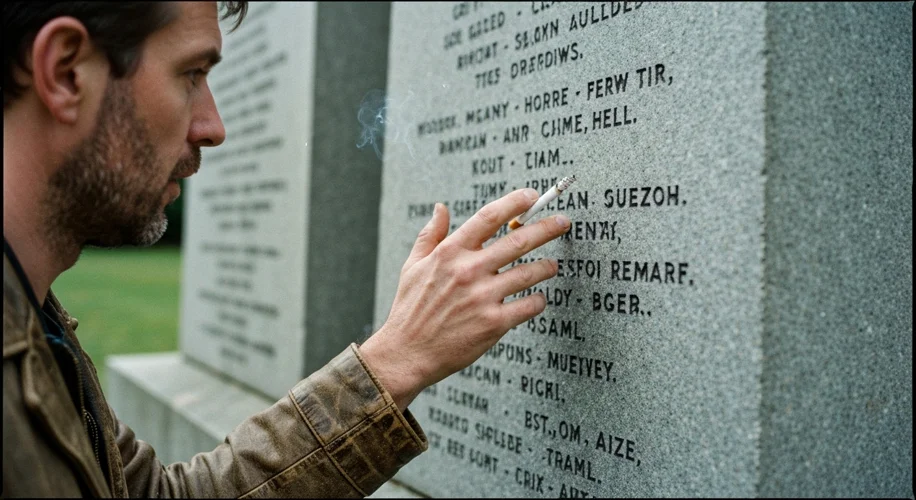

The simple, almost mundane act of lighting a cigarette from a memorial, as might have happened recently, serves as a stark reminder of a profound human endeavor: commemoration. It’s a moment that, while potentially disrespectful to some, unlocks a vast, complex history of how societies grapple with memory, honor their past, and imbue objects with collective meaning.

From the earliest cave paintings to the towering monuments of today, humanity has always sought ways to etch significant events and individuals into the fabric of existence. These aren’t just inert objects; they are vessels of stories, embodiments of sacrifice, and tangible links to a shared heritage. The urge to remember is as old as consciousness itself, a desperate attempt to anchor fleeting moments against the relentless tide of time.

Consider the ancient world. The Egyptians built pyramids, not just as tombs for pharaohs, but as colossal testaments to divine kingship and the promise of an afterlife. These weren’t merely structures; they were eternal messages etched in stone, designed to awe and inspire for millennia. The Greeks erected statues of their gods and heroes, fostering civic pride and a connection to foundational myths. Even the Romans, masters of empire, understood the power of public works – triumphal arches, temples, and vast forums – all served as constant reminders of military victories, divine favor, and the might of the state.

The nature of commemoration, however, shifts with culture and context. In many indigenous cultures, memory is not solely inscribed in stone but woven into oral traditions, ceremonies, and the landscape itself. Sacred groves, ancestral lands, and the very act of storytelling become living memorials, passed down through generations. This contrasts sharply with the monumental, often centralized approach seen in many Western societies, where the physical presence of a statue or a building stands as the primary locus of memory.

The advent of mass conflict, particularly the World Wars of the 20th century, irrevocably changed the landscape of commemoration. The sheer scale of loss demanded new ways of remembering. The ‘Great War,’ with its unprecedented casualties, shattered the old certainties. Suddenly, the glorification of military might felt hollow. Instead, a profound need arose to memorialize the ordinary soldier, the collective sacrifice, and the shared grief. This is when the Field of Remembrance, the simple tombstone, and the cenotaph – the empty tomb – gained prominence. These were no longer about celebrating victory but about acknowledging loss and fostering a solemn, often poignant, reflection.

Think of the iconic poppies worn on Remembrance Day. A simple flower, plucked from the fields of Flanders where so much blood was shed, transformed into a powerful symbol of remembrance. It’s a testament to how everyday objects, imbued with emotional resonance and historical association, can become potent mnemonic devices. Or consider the solemnity of the Eternal Flame, burning ceaselessly at war memorials, a constant vigil for those who perished.

But commemoration is not a static practice. It is dynamic, evolving, and often contested. Who gets remembered? How are they remembered? What stories are told, and whose voices are silenced? The removal or recontextualization of statues, the renaming of streets, and the debates surrounding historical figures all highlight the ongoing negotiation of public memory. What one generation venerates, another might question. The incident with the cigarette, while seemingly small, can be seen as a micro-level example of this tension – an individual’s casual act interacting with a symbol of collective memory, forcing a reflection on the meaning and sanctity we ascribe to these markers.

Our modern era, with its digital footprint and instant communication, presents new challenges and opportunities for commemoration. Virtual memorials, online archives, and social media campaigns allow for broader participation and more immediate forms of remembrance. Yet, the enduring power of the physical monument, the tangible object that one can visit, touch, and stand before, remains undiminished. It offers a different kind of connection, a groundedness that the digital realm often struggles to replicate.

Ultimately, memorials and acts of commemoration are more than just tributes to the past. They are active forces shaping our present and our future. They are how we tell ourselves who we are, where we come from, and what we value. They are the silent language of stones, the whispered tales of the wind through a memorial garden, reminding us that history is not just something we study, but something we actively carry with us.