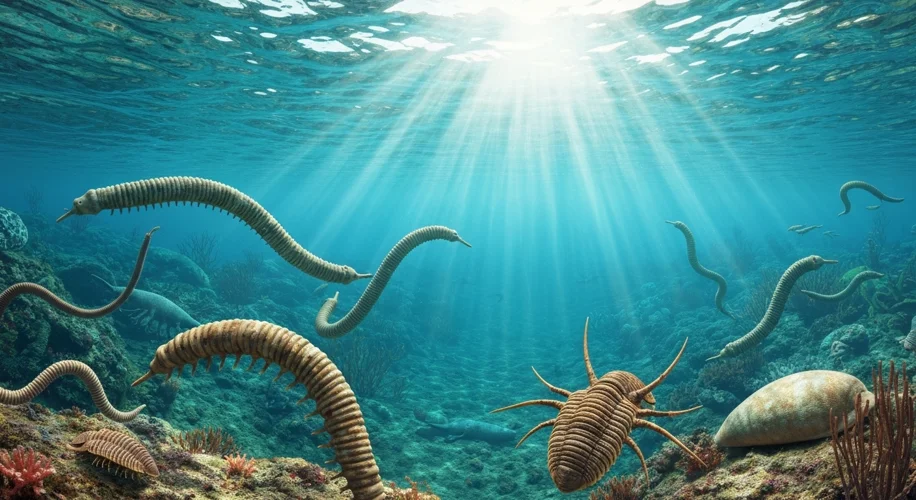

Imagine a world teeming with life, but not as we know it. A vibrant, alien landscape from half a billion years ago, during the Cambrian Period. This was an era of unprecedented evolutionary innovation, often called the ‘Cambrian Explosion,’ a time when the blueprints for most modern animal life were laid down. Yet, for decades, a significant gap existed in our understanding of this critical period. The fossil record, while rich, was frustratingly incomplete, leaving many fundamental questions about early animal development unanswered.

One such enigma revolved around the origins of the anus, a seemingly simple, yet profoundly important, anatomical feature. For many early animals, the digestive system was a simple, blind pouch – food went in, and waste came out the same opening. The evolution of a separate, posterior opening for waste elimination marked a crucial step forward, allowing for more efficient digestion and more complex body plans. But the precise moment and the organism that first sported this evolutionary breakthrough remained elusive, buried deep within the geological strata.

Then, in a discovery that sent ripples through the scientific community, a remarkable fossil emerged from the ancient rocks. Unearthed from the Chengjiang Biota in China, a treasure trove of exceptionally preserved Cambrian fossils, this specimen, dating back an astonishing 500 million years, provided the missing piece of the puzzle. The fossil, identified as a species of Facivermis – a peculiar, worm-like creature – offered an unprecedented glimpse into the anatomy of early bilaterians, the group of animals characterized by bilateral symmetry and, crucially, a through-gut with separate openings for ingestion and egestion.

The implications of this find are immense. Before this discovery, the earliest definitive evidence for a complete digestive tract, including a distinct anus, was from much later periods. This meant that the transition from a simple gut pouch to a more sophisticated system was happening earlier than previously understood, pushing back the timeline for a key evolutionary innovation. The Facivermis fossil, with its unmistakable posterior opening, directly demonstrated that the evolution of the anus was already underway among soft-bodied organisms during the Cambrian Explosion.

Scientists painstakingly analyzed the fossil using advanced imaging techniques. What they found was a small, spindle-shaped body with a series of delicate, feathery appendages radiating from one end, likely used for filter-feeding. But the real revelation was at the opposite end. A small, yet distinct, posterior opening was clearly visible, indicating a complete digestive tract. This wasn’t just a slight variation; it was definitive proof of a separate exit for waste.

The study, published in a leading scientific journal, placed Facivermis as one of the earliest known animals to possess this fundamental trait. This discovery doesn’t just add a name to a fossil; it reshapes our understanding of the speed and complexity of evolutionary processes during the Cambrian. It suggests that the development of complex body plans, which allowed for greater mobility, specialized feeding, and eventually, the vast diversity of animal life we see today, was occurring much more rapidly and with a wider range of experimental forms than previously thought.

This fossil is a stark reminder that the history of life on Earth is a continuous narrative, with each new discovery adding chapters to our understanding. The Cambrian Explosion was a period of intense evolutionary experimentation, and creatures like Facivermis, though perhaps small and short-lived in the grand scheme, played crucial roles in paving the way for the future of life. They were the silent architects, experimenting with new designs, and in doing so, unlocking evolutionary potential that would eventually lead to everything from the smallest insect to the largest whale – and to us.

The humble Facivermis, a creature from 500 million years ago, has finally given us a clearer view of one of evolution’s most significant innovations, proving that even the most mysterious chapters of Earth’s history can be illuminated by the persistent efforts of scientific exploration.