The vast and intricate tapestry of Islamic civilization, spanning centuries and continents, is often perceived through a lens of strict religious doctrine. Yet, beneath this surface of prescribed order, a vibrant and often poignant tradition of homoeroticism flourished, particularly within its rich poetic heritage. This was an era where verses poured forth, celebrating the beauty and longing for the male form, a practice that, while often coded and subject to interpretation, undeniably existed and resonated deeply within its cultural context, even amidst religious proscriptions.

From the sun-drenched courtyards of Andalusia to the bustling souks of Baghdad, male beauty was a recurring theme in the poetry of the medieval Islamic world. This was not a secret whispered in shadowed alleys but a celebrated aesthetic that found eloquent expression in ghazals and qasidas. Poets like Abu Nuwas, a celebrated Persian-Arab poet of the Abbasid era (8th-9th centuries), openly wrote of his attraction to young men, often to the consternation of more orthodox contemporaries. His verses, filled with vivid imagery and passionate declarations, challenged the prevailing norms, earning him both adoration and censure.

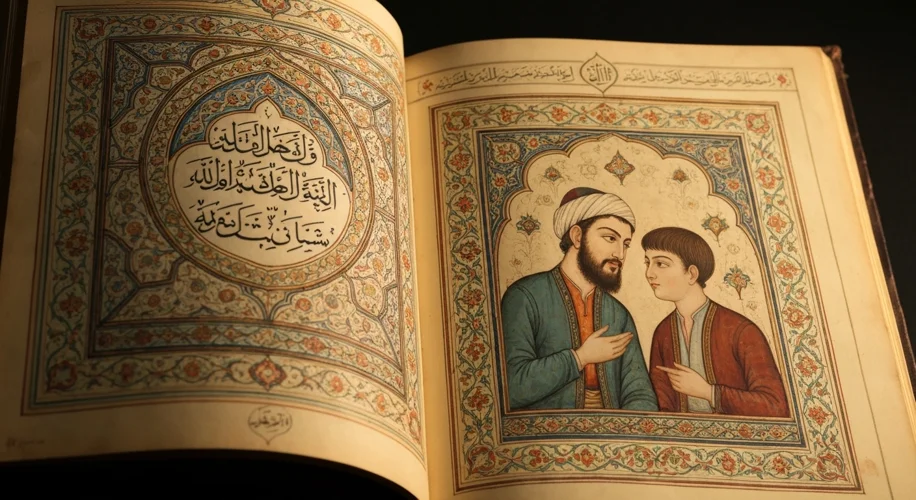

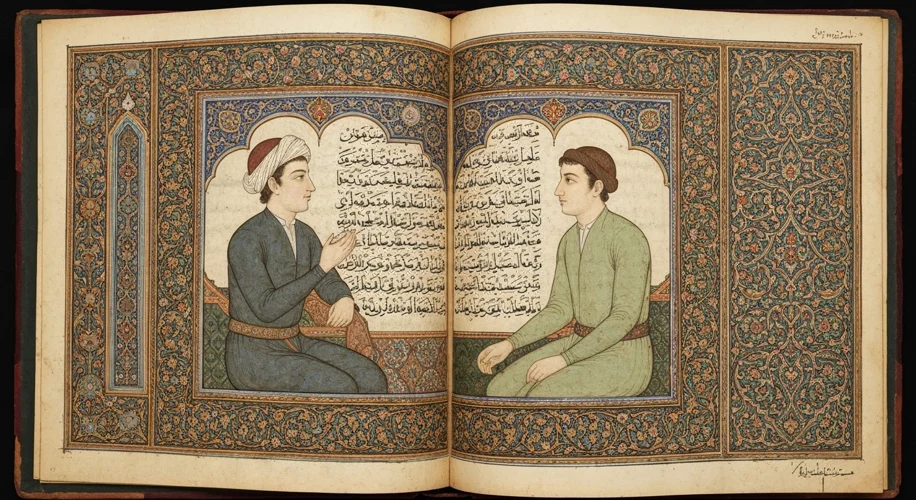

Consider the context: societies where public displays of affection between men and women were highly restricted, yet the intellectual and artistic elite often congregated in spaces where such sentiments, when artfully expressed, could find an appreciative audience. It wasn’t a matter of advocating for a lifestyle as we understand it today, but rather an artistic and emotional exploration of desire. The beloved in these poems was often a beautiful youth – a cupbearer, a soldier, a student – whose physical and spiritual attributes inspired profound affection. This could range from platonic admiration to explicitly sensual longing.

One of the most fascinating aspects of this tradition is its inherent duality. The same religious frameworks that condemned homosexual acts also provided the language and the cultural space for their poetic exploration. This tension created a unique artistic tension. Poets navigated these complexities with remarkable skill, using metaphor, allegory, and subtle suggestion. The beloved’s radiant face could be likened to the moon, their embrace to the warmth of the sun – language that, while seemingly innocent, carried a charge of deeper meaning for those attuned to it.

This tradition wasn’t confined to a single region or period. Across the Islamic world, from the Iberian Peninsula to Persia and beyond, similar themes echoed. In 11th-century al-Andalus, the poet Ibn Hazm, though a proponent of strict Islamic law, penned verses expressing deep affection for male companions. His writings, particularly within his famous work “The Ring of the Dove,” offer introspective accounts of love, desire, and jealousy, often directed towards male figures. This demonstrates that even within seemingly conservative circles, the human heart’s capacity for varied forms of love found expression.

What can we glean from this rich, yet often misunderstood, aspect of Islamic literary history? It reveals a far more nuanced understanding of desire and societal norms in medieval Islamic cultures than simplistic interpretations might suggest. It highlights the power of art to transcend, or at least navigate, religious and social boundaries. These poems were not necessarily a call for social revolution, but rather an intimate articulation of human experience, a testament to the enduring complexity of love and longing that has always been an intrinsic part of the human condition, regardless of time or place.

The legacy of this homoerotic poetry continues to intrigue scholars and readers alike. It compels us to look beyond monolithic portrayals of historical societies and to appreciate the multifaceted nature of human expression, even in the face of religious and social proscriptions. It reminds us that within the grand narratives of history, there are always intricate, deeply personal stories waiting to be rediscovered, stories told in the tender verse of poets who dared to love and to write what they felt.