The mid-19th century. A world teetering on the brink of change, where empires cast long shadows and the whispers of ambition echoed across continents. Into this charged atmosphere stepped the Crimean War (1853-1856), a conflict that, at first glance, might seem like a distant rumble of thunder, but in truth, was a dramatic prelude to the fiercer storms of imperial competition that would soon engulf the globe.

At its heart, the Crimean War was a complex entanglement of religious disputes, strategic ambitions, and the waning power of ancient empires. The Ottoman Empire, once a colossal force, was by the 1850s known as the “sick man of Europe.” Its vast territories, stretching across the Balkans and the Middle East, were increasingly coveted by the ambitious Russian Empire, eager to expand its influence southward and gain access to warm-water ports through the Black Sea and the Dardanelles straits.

The spark that ignited this powder keg was, rather ignobly, a dispute over the rights of Christian minorities in the Holy Land, then under Ottoman rule. Russia, as the self-proclaimed protector of Orthodox Christians, demanded privileges that the French, champions of Catholics, were also vying for. Tsar Nicholas I of Russia saw this as an opportunity to assert Russian dominance and perhaps even hasten the Ottoman Empire’s demise, a prospect that sent shivers through London and Paris.

The British Empire, a global superpower built on trade and naval supremacy, viewed Russian expansion with deep suspicion. They feared that Russian control of the Straits would threaten British maritime routes to India, the jewel in their imperial crown. France, under the ambitious Emperor Napoleon III, was keen to reassert its standing on the European stage and saw an alliance against Russia as a chance to bolster its prestige.

In 1853, Russia occupied the Danubian Principalities (modern-day Romania), territories nominally under Ottoman suzerainty. This move, coupled with the naval clash at Sinope where Russian ships annihilated an Ottoman fleet, led Britain and France to declare war on Russia in March 1854. The ailing Ottoman Empire, though a direct party to the conflict, found itself largely bolstered by the intervention of these European powers. Sardinia-Piedmont, seeking to gain favor and promote its own national unification aspirations, also joined the alliance.

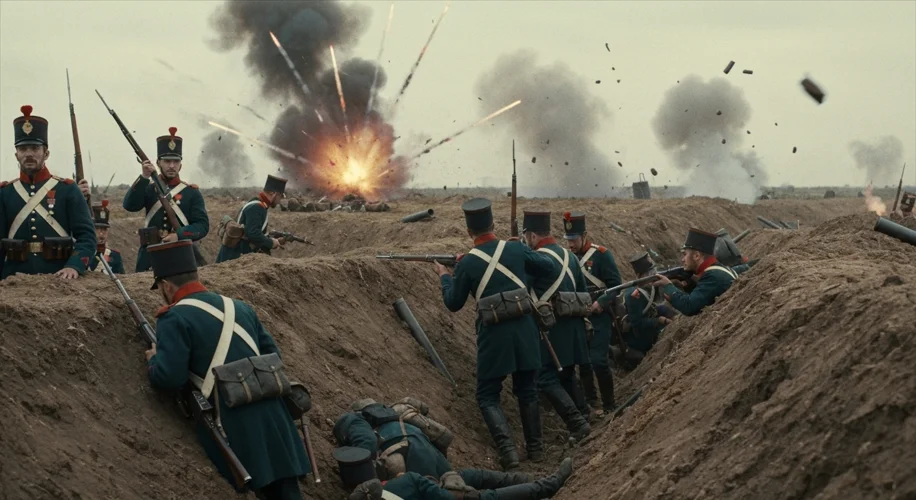

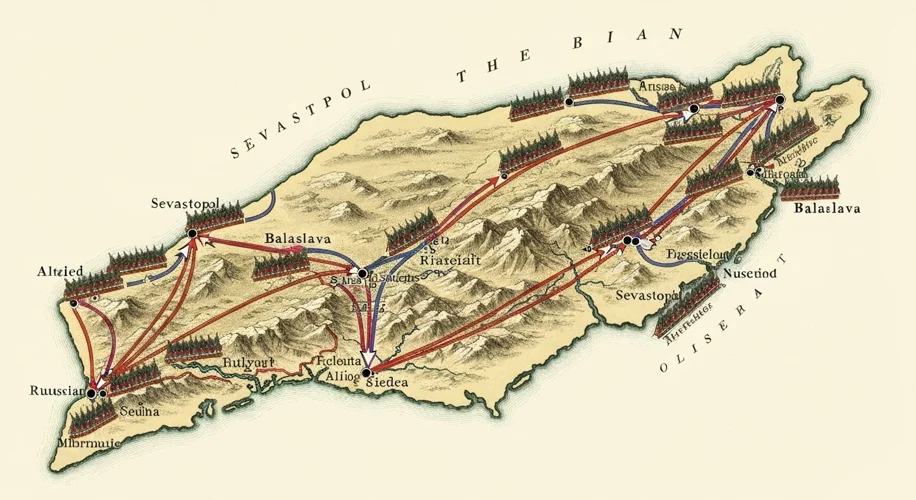

The war that followed was, by all accounts, a brutal and often mismanaged affair. The principal theater of operations was the Crimean Peninsula, a strategically vital piece of territory. The ensuing battles, such as the Alma, Balaclava (famous for the Charge of the Light Brigade), and Inkerman, became legendary for their ferocity and the terrible human cost.

The logistical nightmares and strategic blunders were as prominent as the acts of bravery. Soldiers from all sides endured unimaginable hardship. Disease, particularly cholera and dysentery, claimed far more lives than the actual fighting. Florence Nightingale’s pioneering work in nursing during the Siege of Sevastopol, transforming sanitary practices and dramatically reducing mortality rates, would become a powerful testament to the critical importance of proper care in wartime.

While Sevastopol, the heavily fortified Russian naval base, was the primary objective, the war also saw actions in the Baltic Sea, the Caucasus, and the White Sea. The naval blockade imposed by the Allies crippled Russian trade and communication.

The war concluded in 1856 with the Treaty of Paris. Russia was forced to cede territory, its Black Sea fleet was demilitarized, and the Ottoman Empire’s territorial integrity was, at least on paper, guaranteed by the European powers. However, the underlying tensions that had fueled the conflict remained unresolved.

The Crimean War, often derided as a costly and inconclusive conflict, had profound and far-reaching consequences. It marked the end of an era of Russian dominance in Eastern Europe and the Black Sea. It also exposed the weaknesses of the Ottoman Empire, foreshadowing its eventual dissolution. For Britain and France, it was a demonstration of their combined might, solidifying their roles as global powers and setting the stage for increased colonial competition, particularly in Africa and Asia.

Furthermore, the war revolutionized military technology and medical practices. The increased use of rifled muskets, the telegraph for rapid communication, and the development of ironclad warships hinted at the future of warfare. Florence Nightingale’s legacy, meanwhile, forever changed the face of nursing.

The Crimean War was more than just a clash of arms; it was a geopolitical turning point. It revealed the shifting balance of power in Europe, highlighted the vulnerabilities of established empires, and underscored the growing rivalry between the Great Powers. The seeds of future conflicts, including the scramble for Africa and the intricate alliances that would lead to World War I, were subtly sown in the bloody fields of Crimea. It was a stark reminder that even seemingly localized disputes could ignite global rivalries, a lesson that would echo ominously through the annals of imperial history.